Imperial Oil might not be a household name in the United States, but the company, which is mostly owned by ExxonMobil, is a big name in Canada. There, it’s one of the major players in Canada’s oil sands — the name for the vast fields containing a tarry mixture of sand, water, and the thick, heavy oil called bitumen — that were first mined in 1967. These oil sands, sometimes called “tar sands,” which lie in northern Alberta, are one of the largest oil reserves in the world.

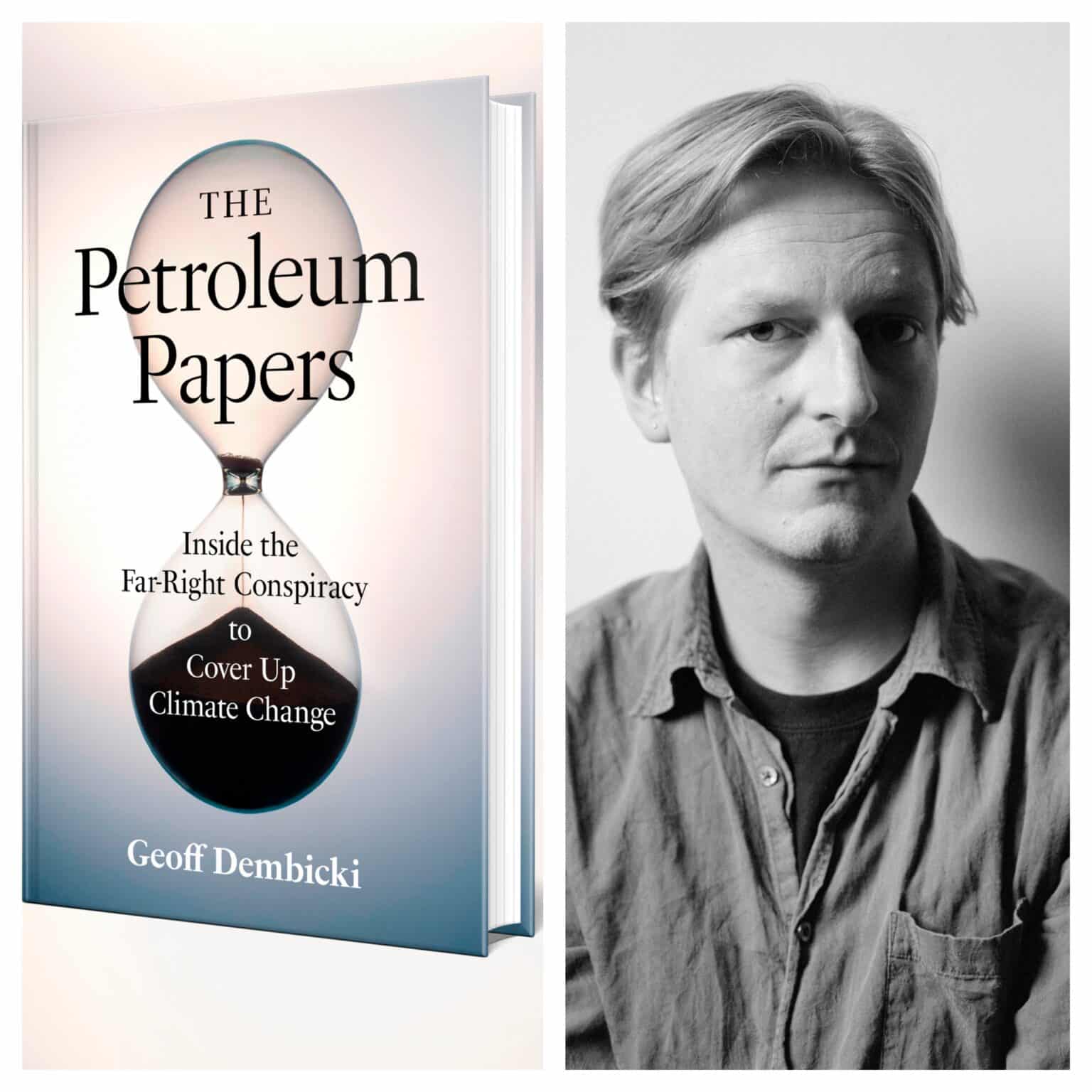

But the oil that comes from them is distinctive in several ways. Oil sands’ unique texture means it takes more money and energy to refine than traditional crude. In addition, its oil is some of the most carbon-heavy in the world, with up to 20 percent higher emissions, and that has drawn the attention of climate advocates. Because of these factors, as Geoff Dembicki explains in his new book The Petroleum Papers: Inside the Far-Right Conspiracy to Cover Up Climate Change (Greystone Books, September 20), oil sands producers and refiners, like Imperial Oil or Koch Industries, are particularly vulnerable to any efforts to mitigate climate change that would increase the already higher costs of extracting and refining bitumen.

Dembicki’s book illuminates for the first time how these industry players profited from Canada’s oil sands and then spun those profits into international networks of climate denial that would help extend the oil sands’ lifetime. “Bitumen from Alberta bankrolled the assault on truth led by companies such as Koch Industries and Exxon,” he writes. Dembicki drew heavily on the Imperial Oil Files we published in 2019, relying on internal company documents that demonstrated not only that Imperial Oil knew about climate change by the late 1970s but also that it studied climate solutions — so that it could try to shut them down. As he explains in the book, “Canada could slow down climate change, or it could tap one of the world’s largest oil reserves — but it couldn’t do both.” It chose the oil sands.

Those oil sands–fueled efforts to spread climate denial and delay action aren’t just a thing of the past. As Dembicki demonstrates, “the machinery of Big Oil’s climate crisis denial” continues its work influencing U.S. and Canadian politics even today.

We spoke with Dembicki ahead of the release of The Petroleum Papers. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Lindsey J. Smith

I want to start with a really simple question: Why write about the oil sands?

Geoff Dembicki

For me, it’s kind of personal because I was born and raised in Edmonton, Alberta. That’s only a few hours’ drive south of the oil sands and, literally, my childhood home was just down the road from a huge oil refinery, and friends and family worked in the oil and gas industry. As I got older, I just wanted to have a better understanding of the industry. And then, of course, once I learned about the massive climate impacts it was creating, and how some of the companies involved with that industry had covered up those impacts and lied to the public that just got me more and more curious.

SMITH

Do you think that other people, even people who are informed about climate change, are aware of the oil sands and of their climate impact?

DEMBICKI

There is a bit of awareness of that, especially in Canada. But part of the reason I wanted to do this book was to really educate readers in the U.S., and in Canada, and all over the world, just about the massive climate impacts that this gigantic oil industry has created. I think when a lot of Americans imagine foreign oil, they’re thinking about like Saudi Arabia, or something, but a huge part of the oil that Americans use every day, and that Canada sends to the U.S., comes directly from the oil sands. And it’s not just like the physical properties of oil that affect what’s happening with climate change. As I explain in the book, there’s a long history of sort of very powerful conservative forces — like Koch Industries, or even going back to Howard Pew in the 1950s and ’60s, and these are people who had a very sort of reactionary, far-right view on the world — and Canada’s oil was important to those types of business people and really funded and made possible this torrent of a very conservative politics, which has had a massive impact on our ability to deal with the climate emergency.

SMITH

A great example of that in the book is the Pine Bend refinery owned by Koch Industries.

DEMBICKI

Yeah. I had known that Koch Industries owned and operated this refinery in Minnesota for a while, but I don’t think I knew how central it was to their company and to their history until I started doing more research for this book. Because it [is] placed so closely to the Canadian border, they could import all of this oil from Canada, which other U.S. refiners didn’t usually take because it was lower quality and required specialized equipment. And so the Kochs were able to do that in their Minnesota refinery and then they can sell the processed oil as gasoline and whatever else at extremely high margins. This created so much money for Koch Industries in the early days that it really allowed the company to become the massive industrial behemoth that it is now. And then, of course, everyone knows the political impact of the Koch brothers becoming so wealthy, which is like an absolute restructuring of our entire political system along free market, anti-government, climate denying lines. So I was just amazed at the central role that oil from Canada played in all of that.

SMITH

I think that’s something that will surprise a lot of readers. Beyond Koch Industries, I’m wondering if you could briefly summarize the web of denial connected to the oil sands?

DEMBICKI

Part of the reason we named the book “The Petroleum Papers” is because I was drawing heavily on this large archive of documents that DeSmog and some others obtained, called the Imperial files, which is a record going back decades of what this company discussed internally in terms of the environment and climate change. Imperial Oil was doing all of this research on climate change, going back to like the 1960s even, and then sharing a lot of that research with Exxon executives. The documents are quite, quite amazing and kind of because they show how scientists inside Imperial and Exxon not only studied climate change internally long before the public knew about it, but they also anticipated that climate change would become a major public policy issue. They were really worried that there would be government regulations that would make their oil sands operations no longer profitable. And so before this issue was even clearly defined for the public, Imperial Oil was already figuring out ways to not only discredit the science of climate change, but also to discredit solutions that could fix the climate emergency too.

SMITH

What solutions were they studying?

DEMBICKI

There’s a document from 1993 that was one of the most alarming that I saw in the entire course of doing research for this. Basically, in the early ’90s, climate change was just starting to become a publicly known issue, but it was very ill-defined so people didn’t really know what to think of it. So Imperial Oil decided to model a bunch of different potential solutions for climate change internally so it would know how to respond. Imperial studied a bunch of different solutions… [and] determined that if there was this price on carbon emissions across the whole economy, this could actually have a really big positive impact on fighting climate change. And then, this part, which was not known before and it was just included in a few footnotes in Imperial’s research, was that in the early days of bringing in such a policy, there would be an economic hit mostly through oil refineries and stuff being closed down. But Imperial actually determined that all of the tax revenue from a carbon price would create this huge amount of money that governments could then spend on green infrastructure and other forms of climate stimulus. And this would actually have a positive impact on the economy. I was just floored by that because it’s like, decades and decades ago, Imperial basically acknowledges that you could do a big part in fixing climate change, and it actually wouldn’t hurt the economy at all, it would probably be good for it. It would just be bad for Imperial Oil, and the oil sands. In this document in 1993, Imperial Oil came up with a confidential plan to misrepresent its own research to policymakers and government and media. There were all of these talking points emphasizing the uncertainty of climate solutions, how it would be bad for the economy, it would hurt international competitiveness. At this very early stage, when we could have made a big impact in fighting the climate emergency, Imperial had already planted these seeds of sabotage and denial.

Read: Exxon Could Have Helped Stop Climate Change 30 Years Ago, ‘Proprietary’ Docs Show

SMITH

Wow, that’s infuriating. A lot of the latter half of the book focuses on these climate lawsuits that have come up in the last few years, including some led by a lawyer named Steve Berman, who managed to finally get a ruling in the courts against Big Tobacco. He and others are now trying to prove a similar thing with Big Oil: that these companies knew that their products were harmful, and they misled the public about that. So far, these climate lawsuits haven’t succeeded, but I’m wondering if you have any thoughts on what it might take for one to succeed?

DEMBICKI

I mean, it’s definitely a long game. With tobacco, it took decades to get any sort of ruling against the industry. That said, there’s been climate lawsuits against Big Oil, I believe, filed by more than 20 jurisdictions in the U.S. Those lawsuits haven’t resulted in any big rulings against the industry yet, but the fact that they’re still all sort of moving forward and clearing procedural hurdles is a big deal. To me, though, the most significant thing that these lawsuits do is really change the narrative around climate change. For so long, we’ve had this idea that no one specifically can be held responsible for climate change because it’s something that we all contribute to. But the climate change lawsuits flip all of that on its head, and they point directly at the oil and gas industry. And it’s not just for the emissions that that industry releases, even though they’re significant. It’s the fact that we had all these really good opportunities to bring in meaningful legislation and to clean up the economy, and the oil and gas industry has played a really bad faith role in sabotaging those solutions, spreading denial about them, confusing the public, flooding politics with their money. These lawsuits are pointing blame at specific companies, specific executives, specific industry groups, and I think that we’re still in the early days, but that’s really going to profoundly change how people see the climate emergency.

SMITH

One of the lawsuits in particular in the book that caught your attention is a case in Colorado against an oil refinery operated by Suncor, a Canadian oil sands company, in the greater Denver area. The lawsuit names both Suncor and Exxon and calls out the oil sands as a major contributing factor to the pollution locals are dealing with. Why is that lawsuit significant?

DEMBICKI

That one was interesting to me because it specifically named Suncor and Exxon. When I heard about that, I was like, “Oh, this is a lawsuit against the oil sands.” Suncor is the company that grew out of Sun Oil, which created the first commercial oil sands operation back in the ’60s. And the second big commercial oil sands operation was started by Imperial Oil, the Exxon subsidiary. Essentially, it’s litigation against the entire Canadian oil sands industry.

SMITH

Another thing that stood out to me in the book was that some of the U.S.’s early support for developing Canada’s oil sands had to do with wanting to have a friendly source of oil in the face of communism. I feel like we’re in a very similar moment right now, where oil and gas companies are capitalizing on a global political crisis to expand production. What can we take away from that past push to develop the oil sands that also applies to this moment we’re in?

DEMBICKI

I think there are two big takeaways for me, or almost like general principles of disinformation that I have observed taking place over many decades. One of them, as you pointed out, is that the oil and gas industry always, always loves to use a global political crisis for its own favor. Of course, the oil and gas industry isn’t in the business of trying to provide good faith solutions to geopolitical problems. They’re looking out for their profits, and that’s always been the case. So I think we can always expect oil and gas companies to try to turn any large global crisis in [their] favor. The second big pattern I noticed was at the moments of greatest possibility in fixing the climate emergency, that’s when the disinformation and the torrent of denial will be at its loudest. When governments are close to bringing in huge structural changes to the economy to fight climate change, when that poses the biggest economic threat to oil and gas companies, that’s when their denial machine really just cranks up as loud as possible.

Learn more about these issues by checking out Dembicki’s book and diving into the Imperial Oil Files.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts