This story is part of a DeSmog series on the influence wielded by the gas lobby in Europe and was developed with the support of Journalismfund.eu

WILHELMSHAVEN, Germany — For 150 years, heavy industry has been the lifeblood of the German port of Wilhelmshaven, a hub for shipbuilding, plastics, coal and steel. Now, the city is at the forefront of the country’s dash to break its dependence on Russian gas.

On Saturday, a newly built jetty is due to welcome the Norwegian-flagged Höegh Esperanza, a 280-metre vessel capable of offloading cargoes of natural gas supercooled into liquid form, then shipped across the ocean in specialised tankers.

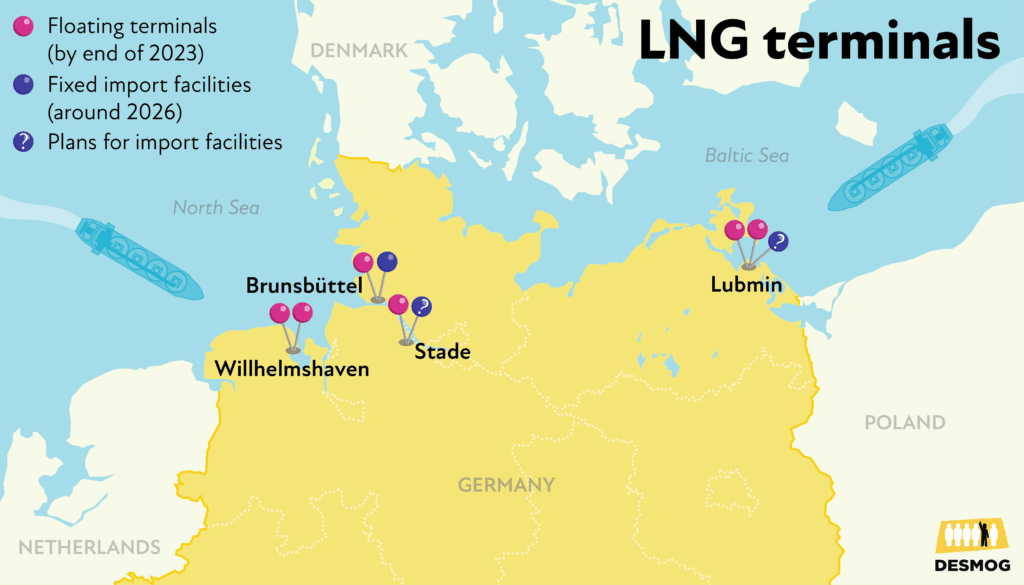

The facility is the first of six such floating units slated to berth at various points along Germany’s coastline over the next year, where liquid gas will be converted back into its gaseous state and fed into the country’s gas grid. Up to three onshore equivalents will boost import capacity further. This string of new infrastructure will enable the country to buy enough liquefied natural gas (LNG) from producers such as Qatar and the United States to cover up to a third of its present-day needs, officials say.

Uniper, RWE and other big German utilities argue that pivoting to LNG is Germany’s only viable substitute for Russian pipeline gas, which accounted for more than half the country’s imports before President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine triggered a frantic search for alternatives.

Climate campaigners, however, see the new piers and pipelines as ominous signs that the gas lobby has finally achieved a long-standing goal to lock Germany into the $100 billion global LNG market – threatening to keep Europe’s biggest economy hooked on fossil fuels for decades to come.

“A lot of new fossil infrastructure is being installed, and environmental and climate experts are very worried that this could go far beyond the infrastructure needed for the short term, and create new fossil lock-ins,” said Nina Katzemich of LobbyControl, a transparency campaign group based in Berlin and Cologne.

That’s potentially very bad news for the climate: The huge amount of methane that leaks during the production, transport and storage of LNG means that the carbon emissions associated with importing the fuel could be up to ten times higher than for the equivalent amount of Russian pipeline gas, researchers say.

What’s more, Germany could sidestep the need to build the planned onshore LNG terminals altogether if it took more aggressive steps to curb energy demand by ramping up plans to install more heat pumps in homes, and renovate buildings, according to a new report.

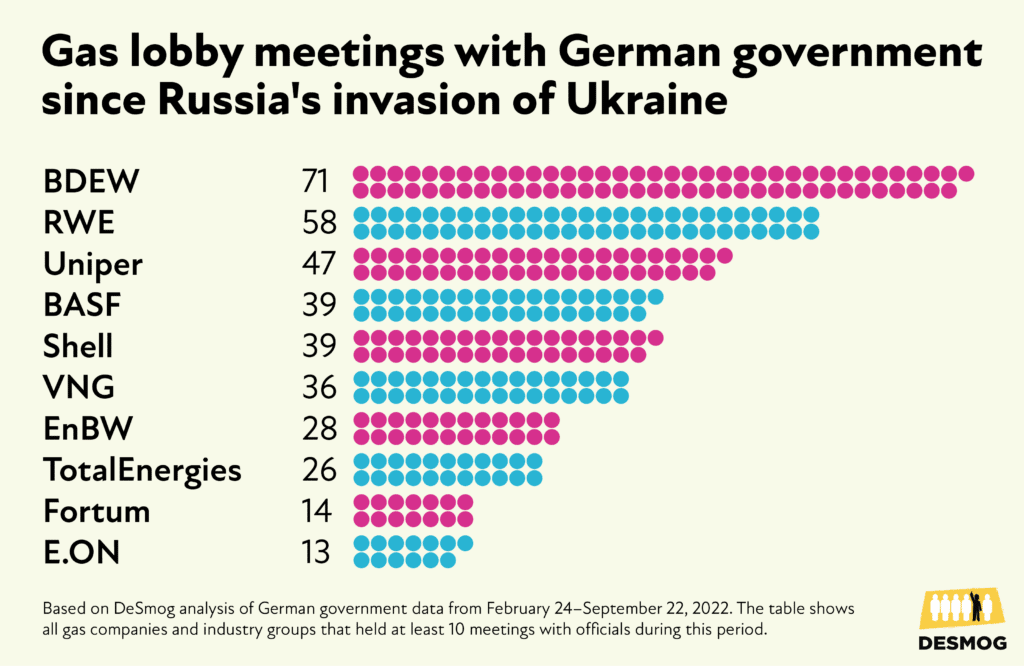

With gas lobbyists holding hundreds of meetings with officials since Russia’s February 24 invasion of Ukraine, according to DeSmog analysis of official records, campaigners accuse the industry of crowding out discussion of measures to reduce demand for its product – with disastrous consequences for the climate.

“We need to invest more in renewable energy, not lock in infrastructure or exploit other countries for our own ‘energy security’,” said Stefanie Eilers, a campaigner in Wilhelmshaven from the Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union, an environmental group with more than 500,000 members. “It’s fossil fuel madness.”

Hopes Resurrected

The gas lobby’s project to plug Germany into the global LNG market dates back to at least 2005, when E.ON Ruhrgas – a subsidiary of gas company E.ON – first proposed plans for an import terminal in Wilhelmshaven.

Until last year, Germany relied mostly on plentiful supplies of cheap Russian pipeline gas, as well as importing LNG via France, Spain and the Netherlands. As recently as April, 2021, Uniper, then one of Europe’s biggest buyers of Russian gas, was forced to shelve the latest attempt to open an LNG terminal in Wilhelmshaven, citing a lack of demand.

Calculations changed dramatically after the invasion of Ukraine. The German government and the gas industry, which has long enjoyed a powerful voice in energy policy, fell into lockstep on the need to rapidly import LNG as Russia restricted gas supplies in response to Western sanctions. The move threatened to cripple Germany’s economy, which relied on gas for about 27 percent of its total energy consumption in the first half of this year, mostly for heating and industry, according to Clean Energy Wire.

The Green party, a partner in Germany’s ruling coalition, which unveiled sweeping measures to boost wind and solar this spring, became a strong LNG advocate. Green politician Robert Habeck, Germany’s vice-chancellor and minister of economy and climate action, called for new gas import infrastructure at “Tesla speed” – a reference to the rapid rollout of a Gigafactory near Berlin.

Weeks later, Germany released nearly three billion euros to lease four floating LNG import terminals from RWE and Uniper, including the Höegh Esperanza at Wilhelmshaven. In May, the government passed legislation to accelerate the deployment by relaxing planning rules. The government has portrayed the LNG terminals as stopgap measures. But licences allowing the infrastructure to operate for up to 20 years have raised fears the terminals are here to stay.

“Companies had failed to build terminals for years. They never succeeded because they didn’t have a business case,” Constantin Zerger, head of energy and climate protection at Hanover-based nonprofit Environmental Action Germany, told DeSmog. “After the war started, they weren’t talking about economic feasibility but about energy security, and at that point the government decided to jump on all the existing plans.”

After a bleak period for LNG, when a combination of the COVID-19 pandemic, climate concerns and investor jitters had weighed heavily on investment, industry groups on both sides of the Atlantic seized on the Ukraine invasion to revive the industry’s fortunes.

Gas Infrastructure Europe, the association of European gas infrastructure operators; Eurogas, which represents the wholesale, retail and distribution sectors, and LNG Allies, an industry association in the United States, which is vying with Qatar and Australia to be the world’s top exporter of the fuel, all issued statements urging the EU to invest in LNG infrastructure.

Canada’s oil and gas industry also spied opportunities. In January, as tensions between Russia and Ukraine rose, Canadian officials and Calgary-based Pieridae Energy pitched the idea of exporting Canadian LNG during a virtual meeting with German officials, as DeSmog has previously reported. The meeting took place as part of the Canada–Germany Energy Partnership, established in March 2021 to foster “clean energy” trade opportunities – including in hydrogen and LNG.

‘Political Decision’

German utilities, gas network operators and international oil companies were quick to engage with the government as the Ukraine crisis escalated.

Gas and energy industry representatives met with German officials at least 547 times in the seven months following the invasion, according to responses to a parliamentary written question filed by three Left Party MPs in October and analysed by DeSmog. The meetings included conversations, telephone calls, written exchanges, roundtables and the occasional shared press conference, with executives representing LNG projects planned in Brunsbüttel, Stade and Lubmin engaging regularly with Habeck and other high-ranking officials.

Campaigners acknowledged the need for the government to discuss a temporary response to the energy crisis – but said they feared gas companies had used their extensive access to promote a long-term role for fossil fuels, despite Germany’s target to reach climate neutrality by 2045.

“If political decision-makers are only listening to one side of the story, we can assume that their decisions will also serve these interests, rather than that of the public,” said Sam Beiras, spokesperson at the WeiterSo! Kollectiv, a pressure group seeking to challenge the gas lobby’s influence in Germany. “It’s a big scandal in our eyes.”

The German Association of Energy and Water Industries (BDEW), a major lobby group representing the gas industry, held 71 meetings with Habeck and other officials over the seven-month period. The group is led by managing director Kerstin Andreae, a former Green party member of parliament, who backed the bill to ease planning rules for new LNG terminals.

Uniper, which was nationalised in September after suffering huge losses when Russia restricted gas sales, held 47 meetings with the government, while its previous owner, Finland’s Fortum, held 14. Uniper told DeSmog the meetings pertained to the government’s moves to stabilise the company’s finances, and its request that the company build and operate the LNG import terminal in Wilhelmshaven, and procure LNG supplies globally.

RWE, which is backing the planned LNG terminal at Brunsbüttel, was represented in 48 meetings. Last week, U.S. oil company ConocoPhillips and QatarEnergy signed a 15-year deal to provide the company with two million tonnes of LNG annually from 2026. RWE has also struck deals to buy LNG from Abu Dhabi’s state oil company Adnoc.

“It was a political decision by the federal government to replace pipeline-bound natural gas with LNG,” RWE said in an email to DeSmog. “The goal was clear: to make Germany less dependent on Russian imports and to create security of supply for industry and private households as quickly as possible.”

Markus Krebber, RWE’s chief executive, and Uniper Chief Executive Klaus-Dieter Maubach both held talks with state secretary Jörg Kukies on a “collaboration” with Senegal. Neither company has spoken publicly about pursuing gas plans in Senegal, but reports of a potential gas partnership between the German government and Senegal have met with fierce criticism from climate campaigners.

German officials also spoke regularly with multinational oil and gas companies in the first months of the war, including with the chief executives of Shell, TotalEnergies and Equinor. These meetings were held on a variety of subjects, including “energy supply” and quitting Russian oil, but also on hydrogen.

Companies and groups referenced in this article were approached by DeSmog for comment but had, unless stated otherwise, not responded prior to publication.

‘A Very Long Bridge’

Germany’s government has sought to soothe concerns over the potential climate impact of the LNG infrastructure with reassurances that the terminals will be adapted to transition to hydrogen – which the gas industry portrays as a sustainable fuel.

Complying with the 2015 Paris Agreement to avoid catastrophic climate change implies a complete phaseout of fossil fuels – including natural gas, said Susanne Ungrad, an official speaking on behalf of the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action.

“It is therefore important that wherever new gas infrastructure is built, the switch to renewable energy sources such as hydrogen and its precursors must also be considered and planned from the outset,” Ungrad said.

The floating terminals will transition to hydrogen and other “clean” liquid gases as soon as 2025, their operators say, while the onshore import terminals will start processing renewables-powered green hydrogen around the same time.

Experts have questioned the economic and technical feasibility of those promises.

Although hydrogen does not emit any polluting gases when combusted, the vast majority of current global production is in the form of ‘grey’ hydrogen – which is produced using natural gas. Cleaner ‘green hydrogen’ – made by splitting water via electrolysis – is being promoted as a vital climate solution by governments and industry. However, this expensive process is both energy- and water-intensive, and currently only operates at pilot scale.

A report published by the nonprofit Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research in November said it was “uncertain” if there was a future hydrogen use case for the LNG terminals, and warned they risked becoming stranded assets. The German government has characterised such concerns as unsubstantiated.

What does seem clear: Ballooning emissions associated with LNG production in the coming years could be very damaging to the climate.

In November, Norwegian research firm Rystad Energy shared research with the BBC that showed the carbon emissions caused by producing and shipping LNG to Europe are potentially ten times higher than those from Russian pipeline gas – due in part to the extra energy required to cool the gas for shipping, then regasify it on landing.

The analysis concluded that Europe would import an additional 35 million tonnes of carbon emissions if it replaced all its Russian pipeline gas by the end of next year, compared to 2021. Germany’s annual emissions are about 675 million tonnes.

Moveover, a November briefing by Climate Action Tracker found that plans to expand LNG will push the world further off track to meet the Paris Agreement goal to limit the rise in average global temperatures to 1.5C.

If all the current planned projects go ahead, most of which are in North America, the global LNG industry will overshoot the emissions limits in the International Energy Agency’s net zero pathway by the equivalent of 1.9 gigatonnes of CO2 emissions per year by 2030 – about the same as the annual emissions produced by Russia, the organisation says.

Environmental Action Germany has placed climate change at the centre of a legal case it has filed against Uniper’s floating terminal in Wilhelmshaven, which also raises concerns over accidents and water rights, and demands the facility operates for a maximum of 10 years.

“They call it (LNG) a bridge technology but it keeps getting longer,” Jochen Martin, an environmental campaigner from Wilhelmshaven, who is not involved in the lawsuit, told DeSmog. “It’s becoming a very long bridge indeed.”

‘Not Sustainable’

And then there is the cost.

Opponents of LNG infrastructure are concerned that the gas industry’s access to the government has sidelined valid concerns over the economics of the new projects – whose cost has doubled from initial estimates to more than six billion euros.

Rising natural gas prices mean that importing LNG could translate into additional costs of up to €200 billion by 2030 relative to the historical average, according to a report by energy think tanks E3G, the Institute for Energy, Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), Wuppertal Institut and Neon.

That would double bills for consumers – and soak up subsidies that would be better spent on slashing demand for imported gas by significantly expanding the government’s plans to make older buildings more efficient. Such additional demand reduction measures could negate the need to build the onshore LNG import terminals altogether, the report found.

“We cannot just subsidise the costs (of LNG) – this is not in any way sustainable, neither financially, nor from a climate perspective,” said E3G’s Mathias Koch, who co-authored the report. “It would be disastrous to continue to go down that path.”

With the Ukraine invasion sending prices for LNG soaring, analysts say the extra cost is driving a faster switch to renewables in many markets – meaning LNG demand could peak sooner, and leave Germany’s new import terminals idle.

“There’s no guarantee there’ll be that demand for LNG,” said Clark Williams-Derry, gas analyst at IEEFA, who predicts the planned onshore terminals will not live out their operational life. “In the long-haul they won’t get utilised.”

That’s cold comfort for climate campaigners who are now scouring the horizon for signs of the next floating units to move into place.

Pacing a promontory jutting into the River Elbe, not far from the port of Stade, where LNG tankers will soon start to offload, Jörg Schrickel says it will be impossible to stop a planned floating terminal docking by the end of next year.

The energy consultant and environmental campaigner says the battle is now to persuade the government to introduce restrictions on onshore import terminals planned to open in 2026, including one at the site of a Dow Chemicals factory in Stade.

“We can create new jobs with energy savings and renewable energy, but that’s not being talked about at all,” Schrickel said, as distant chimneys from Stade’s industrial belt billowed smoke above a grey ocean vista. “We need to restrict this fossil fuel lock-in – at all costs.”

Editing by Matthew Green.

Additional research by Ingvild Deila and Rachel Sherrington.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts