Not too long ago, more than 80 percent of U.S. gas supplies were produced by “mom-and-pop businesses”—companies with an average of a dozen employees and a market capitalization of less than $500 million.[1]

But when ExxonMobil announced its successful acquisition of XTO Energy in November 2010, the face of the gas industry changed enormously.

With each passing day, the list of the top gas producers is starting to look a whole lot like the list of Big Oil companies.

Today, the natural gas industry is dominated by companies whose names are well known – ExxonMobil, BP, Shell, ConocoPhillips and Chevron are all in the top 10. It turns out that the “clean” gas industry is really just the dirty oil industry in disguise.[2]

ExxonMobil is now the largest natural gas producing company in the U.S., producing about 16% of the nation’s total consumption.[3] ExxonMobil went on a “year-long buying spree” in 2010, snapping up XTO Energy in June 2010 for $31 billion to become the largest U.S. gas producer.

Photo: Ed Schipul, http://www.flickr.com/people/eschipul

Exxon then acquired Denver-based Ellora Energy Inc. in July 2010 for $695 million, and spent another $575 million in December to purchase Petrohawk Energy Corp’s wells and reserves in Arkansas’s Fayetteville Shale. With an additional $75 million, Exxon bought up Petrohawk’s pipeline assets in the Fayetteville Shale.[4]

But Exxon isn’t the only oil major focused on dominating shale gas production. Shell, Europe’s largest oil company, is set to produce more gas than oil in 2011, a first in the company’s 104-year history.[5]

In one of the biggest oil and gas deals of 2010, Royal Dutch Shell Plc agreed to buy most of East Resources Inc., one of the largest independent gas companies in the Appalachian Basin, for $4.7 billion in cash, increasing Shell’s total shale gas acreage in the U.S. to about 3.6 million acres.[6] Some analysts say that acquisition was made strategically after the Gulf of Mexico BP disaster, when Secretary Salazar postponed Shell’s permits to drill exploratory oil wells in the Arctic.[7] Shell’s purchase of East Resources also occurred just after its joint acquisition with PetroChinaCo of Australian gas producer Arrow Energy.[8]

Chevron, the second-largest energy company in the U.S., has just completed the purchase of Atlas Energy Inc. for $4.3 billion, which will make it a leading producer of gas from the Marcellus Shale.[9] Hinting at plans for an increase of gas exports, Chevron is also building a $40 billion liquefied gas plant off the coast of Australia.[10]

U.S. gas reserves have caught international attention as well. French oil conglomerate Total SA spent $800 million to form a joint venture with Chesapeake Energy Corp., the country’s second-largest gas producer, with Total acquiring 25% of Chesapeake’s Barnett Shale assets.[11] BP and Statoil have also entered into separate joint ventures with Chesapeake, purchasing gas assets in two major shale plays, the Fayetteville and the Marcellus.[12]

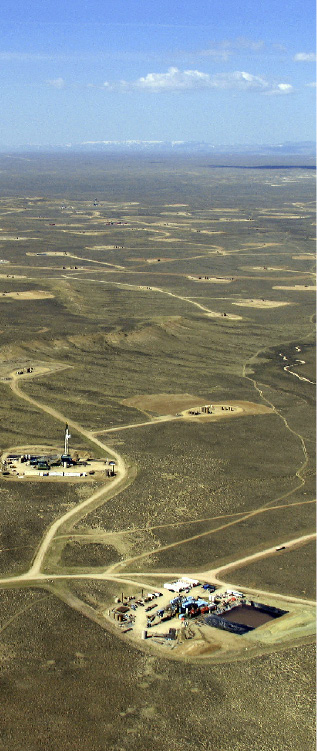

Image: Skytruth, http://www.skytruth.org

In January, Chinese oil giant CNOOC offered Chesapeake Energy $1.3 billion for a third of the company’s stake in its gas reserves. One month later PetroChinaCo. offered EnCana, another gas giant, $5.4 billion for a share in its gas assets.[13] This decisive shift in the energy sector reveals that the oil majors are well aware of dwindling global oil reserves[14] and the new battle to control the “unconventional” fuel market. For energy companies looking to replenish their reserves, the search for oil is increasingly competitive and fraught with emerging complexities.

Exxon’s inability to find new oil, the Wall Street Journal reports, is “a conundrum shared by most of the other large Western oil-producing companies, which are finding most accessible oil fields were tapped long ago, while promising new regions are proving technologically and politically challenging.”[15]

What remains of the world’s oil, about 90%, is nationally owned and so closed to multinational companies like Exxon.[16]

Struggling to find new reserves, Exxon and other oil majors have turned to gas as a proxy. Exxon would have fallen short of their reserve replacement ratio, for the first time in 17 years, had it not been for the vast amounts of newly acquired unconventional gas.[17] Like Exxon, other major oil companies are looking to invest in unconventional gas in order to prolong their highly profitable dominance in the fossil fuels market.[18]

The gas industry trade group Independent Petroleum Association of America (IPAA) downplays the fact that Big Oil is moving in on America’s gas reserves, no doubt hoping to stave off public outcry for the repeal of oil and gas industry subsidies

and tax breaks lavished on some of the wealthiest companies around. Instead, IPAA continues its attempts to project the ‘local’ “independent” reputation of the formerly mom-and-pop gas industry, arguing that a tax increase for gas producers would mean “an enormous, job-crushing tax increase on America’s small businesses who deliver stable supplies of homegrown, reliable energy to U.S. consumers.”[19]

But even back in 2009, before most of the small independent companies were swallowed up by giant multinationals, the top 10 gas producers were responsible for roughly half of all domestic production.[20] With opinion polls showing low public support for oil companies after decades of pollution and global warming denial, perhaps the IPAA fears that Big Oil’s new dominance in the unconventional gas industry will bring increased scrutiny and enforcement.

Recent media reports suggest that more consolidation is likely in the unconventional gas industry this year, with analysts characterizing Texas-based Range Resources Corp. as an “attractive takeover target,” for instance.[21]

The days of the “independent” mom-and-pop gas industry are gone.

Big Oil has taken over.

[6]http://www.businessweek.com/news/2010-05-28/shell-taps-shale-with-4-7-billion-east-resources-buy-update2-.html

[8]http://www.businessweek.com/news/2010-05-28/shell-taps-shale-with-4-7-billion-east-resources-buy-update2-.html

[9]http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2010/11/09/chevron-to-buy-atlas-energy-for-3-billion/?nl=business&emc=dlbka22

[11]http://www.bnet.com/blog/clean-energy/chesapeake-8217s-joint-venture-strategy-hooks-another-foreign-energy-company/1041

[12]http://www.bnet.com/blog/clean-energy/chesapeake-8217s-joint-venture-strategy-hooks-another-foreign-energy-company/1041

[13]http://dailytradealert.com/2011/03/03/exxon-chevron-and-shell-are-betting-51-billion-on-this-commodity-and-its-not-oil/

[17]http://dailytradealert.com/2011/03/03/exxon-chevron-and-shell-are-betting-51-billion-on-this-commodity-and-its-not-oil/

[18]http://www.businessweek.com/news/2010-10-01/oil-majors-to-dominate-u-s-shale-gas-m-a-wood-mackenzie-says.html