This has been a year of dramatic disasters and weather extremes. From tornadoes to droughts to heat waves, the U.S. has been battered.

Unfortunately, the hurricane season that’s about to get firing may not go any easier on us.

Nobody can say in advance where storms are form to strike or whether they are going to make landfall—but everything is lining up for there to be a lot of them in the Atlantic region, and some very strong ones. As you can see from the figure here, we’re just starting the climb towards the peak of the season, which occurs on September 10.

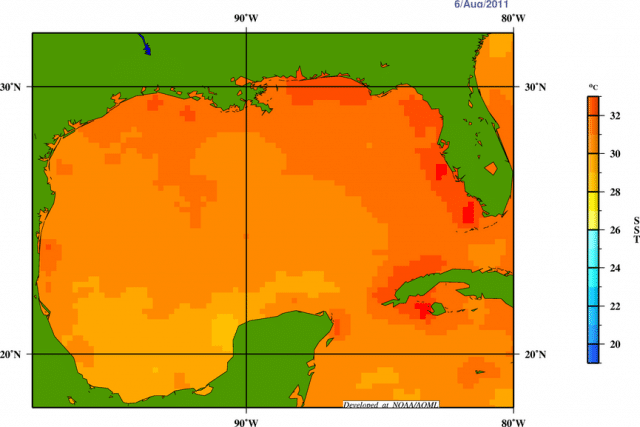

Sea surface temperatures in the main development region for Atlantic hurricanes (pictured above for the Gulf) are the third hottest they’ve been on record. Everything is lining up for there to be a lot of action: 9-10 hurricanes, and 3-5 major ones, NOAA predicts. There have already been 5 tropical storms, but that’s child’s play compared with what’s likely coming.

I have already written about the difficulty of pinning tornado disasters on global warming. And by the same token, I’ve written about why it’s perfectly justifiable to draw climate links for heat waves and declining Arctic sea ice.

Where do hurricanes fit into this picture? That’s tricky—but something worth discussing now, because if there’s a major U.S. land-falling hurricane, everybody is going to be asking about it, just as they always do.

The hurricane story is in some ways more straightforward than the tornado one, but still beset by uncertainty. We have clear theoretical reasons to expect the strongest storms to get stronger, and to rain more—a potentially devastating, but often neglected, aspect of a hurricane’s impact.

In other words, there is every reason to expect that, as we continue our ill-advised experiment with the Earth’s climate, we will indeed reap some devastating whirlwinds.

However, that’s the future rather than the present. Scientists aren’t sure we can yet separate the signal of hurricane intensification from the noise of natural variability—and what’s more, they now also expect total storm numbers to decrease overall, a significant offsetting effect to the expectation of greater intensity. Here’s a consensus statement from last year, by the leaders of this field:

Whether the characteristics of tropical cyclones have changed or will change in a warming climate — and if so, how — has been the subject of considerable investigation, often with conflicting results. Large amplitude fluctuations in the frequency and intensity of tropical cyclones greatly complicate both the detection of long-term trends and their attribution to rising levels of atmospheric greenhouse gases. Trend detection is further impeded by substantial limitations in the availability and quality of global historical records of tropical cyclones. Therefore, it remains uncertain whether past changes in tropical cyclone activity have exceeded the variability expected from natural causes. However, future projections based on theory and high-resolution dynamical models consistently indicate that greenhouse warming will cause the globally averaged intensity of tropical cyclones to shift towards stronger storms, with intensity increases of 2–11% by 2100. Existing modelling studies also consistently project decreases in the globally averaged frequency of tropical cyclones, by 6–34%. Balanced against this, higher resolution modelling studies typically project substantial increases in the frequency of the most intense cyclones, and increases of the order of 20% in the precipitation rate within 100 km of the storm centre. For all cyclone parameters, projected changes for individual basins show large variations between different modelling studies.

Further explanation is provided by NOAA’s Tom Knutson, who states that in his latest modeling study, overall hurricane numbers are expected to decrease in the Atlantic, but at the same time, the frequency of the most intense hurricanes could as much as double by the end of the century. So less storms overall, but also more very devastating ones.

What does this mean for the current hurricane season, forecast to be very active?

Not all that much. Atlantic storms have been very busy since 1995, but scientists still aren’t willing to unequivocally state that global warming is the reason–even if they may suspect an influence.

So in a bad storm year, or with a bad storm landfall, you don’t want to claim that global warming “caused” that season, that storm, or that landfall. Global warming is always operating in the background, and contributing to everything that happens. But there are myriad other factors and variables—like wind steering currents—that also direct how storms form and behave.

Rather, you say this: We’ve seen, again and again, the devastating power of hurricanes. Why anyone would want to mess with the climate system, when an even greater frequency of the worst storms is expected to result, is difficult to fathom.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts