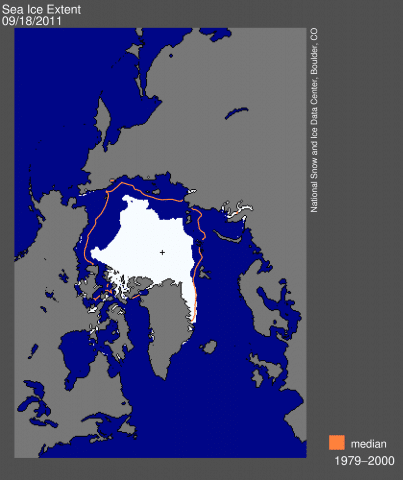

Last week, the National Snow and Ice Data Center came out with the estimate that we did not quite set a record for the minimum extent of Arctic sea this year. Rather, 2011 seems to have come in a slight second to 2007.

However, another scientific group does claim that we’ve hit a new record. Who’s right?

I don’t know, but I don’t think either bit of news is the most important thing to focus on. For as Skeptical Science points out, we also just learned that total sea ice volume reached a new low in 2010 (wonky hide-the-punchline paper here). And that is, to my mind, a much bigger deal than what total sea ice extent is doing on a year by year basis.

Remember, extent is a measure of area covered, and volume is a measure of total ice mass. (More clarification here.)

There is a strong case that volume matters more, because extent can be misleading. Why?

Well, again, as I reported last year in New Scientist:

How can ice volume have kept falling when extent increased again after 2007? Because less and less ice is surviving to see its first birthday. “First-year ice is now the dominant ice type in the Arctic, whereas a few years ago multi-year ice was dominant,” says Barber.

Young ice is thinner than multi-year ice, and thus more likely to break into smaller pieces that melt more quickly, and more likely to be swept out of the Arctic and into warmer seas….And while the area of young ice increased in 2008 and 2009, the amount of multi-year ice continued to fall. “There wasn’t a recovery at all,” says Barber.

And now it seems that total ice volume keeps trending lower—which also means that the day when we’ll have an essentially ice free Arctic for some part of the year draws nearer. What fun the oil and gas and shipping companies will have!

All of this is, yet again, proof that our society just doesn’t know how to think about changes in the climate system.

Consider: We all got very whipped up about a fairly mundane and standard hurricane, Irene, which in the end posed a much smaller threat to New York City than the worst case scenario storm that will come some day (and which we won’t be ready for). But since Irene was proximate and fast moving, it made us all worry, and made many of us think of global warming.

Meanwhile, when real dramatic changes are happening far away from us in a drip, drip, drip fashion, it is virtually impossible to get our attention, unless somebody can claim a “record.”

I wrote recently about a flawed study that nevertheless suggests that climate researchers view the world in a different way than the public, partly due to their personalities as measured on the less-than-perfect Myers-Briggs scale:

Intuition is characterized by “focus on theories,” “ask ‘why’ questions,” “look for patterns and possibilities.” Sensing, by contrast, means “focus on experience” and “Prefer practical, plain language to symbols, metaphors, theories, and abstractions.” The authors suggest this may make average Americans less likely than climate scientists to respond to distant threats about climate change (e.g., to polar bears), and much more responsive to what they perceive around them (i.e., weather).

I think there’s a lot to this, even if I question the underlying scientific methodology of the study. But I do think it’s true that unlike scientists, most people are not easily made to perceive all the ways in which the world around us is changing.

How do you get them to perceive? On this issue, it appears you may have to wait til it affects them–or make them realize that it affects them.

Yesterday I felt a blast of cold air here in D.C., and I thought that, barring another hurricane, we may not get their attention easily again until next year.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts