Read At the Limits of the Market: Why Capitalism Won’t Solve Climate Change, Part 1.

One answer to the question of why free market capitalism has failed to generate technological solutions to the crisis of climate change is that green innovation simply isn’t as profitable as speculation. In an era when financial markets generate record profits and investment banks are too big to fail, the long work of investment, research and construction of new energy infrastructure simply isn’t attractive to profit-seeking corporations.

Faced with the clear failure of the free market to respond to the approaching dangers of climate change, politicians have reacted by attempting to coax corporations into serving the needs of people as well as the bottom line. This is typically referred to as finding “market-based solutions.” It sounds good at first: we’ll harness the best minds in the private sector to develop new technology, create new jobs and solve climate change in the process.

But all too often the phrase “market-based solutions” works as a kind of coded communication. In effect, it signals to corporations that the government will not take any measures that could interfere with their business model. Rather than impose meaningful restrictions on emissions or the extraction of fossil fuels, market-based solutions focus on changing behavior by creating the right set of incentives.

But without strong penalties to go along with those incentives—a stick alongside the carrot—market-based solutions simply end up creating profitable new markets without addressing the underlying economic drivers of climate change.

When the Kyoto Protocol was adopted in 1997, the creation of markets for trading carbon emissions (typically referred to as a cap-and-trade system) was established as the primary means of tackling climate change without endangering profits. The basic idea of carbon markets is simple: establish a cap or limit on the total amount of CO2 that companies can emit. That amount of carbon is then divided up and allocated to different companies through the creation of carbon permits: in order to emit any amount of carbon, each company needs the corresponding permits.

For those companies that emit less than the allotted amount, carbon permits can be traded or sold for additional income. For those companies that produce carbon emissions over the limit, the need to purchase costly permits should function as a reason to innovate and develop low-carbon production methods.

But carbon emissions trading hasn’t lived up to its promise. The world’s largest market for carbon emissions trading, the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS), is failing. The European system is awash in excessive permits, meaning that the price of emitting carbon is so low that corporations have no incentive to clean up their production methods. At the global level, the United Nations Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) is suffering a similar fate.

As Steffen Böhm, director of the Essex Sustainability Institute at the University of Essex contends, “Carbon markets have lost us more than 15 years in the battle against climate change.” A combination of aggressive industry lobbying for additional permits, a lack of transparency and inadequate oversight mechanisms has simply turned carbon markets into yet another profitable arena for speculation, with no measurable effect in terms of reducing emissions.

One of the staunchest critics of the emissions trading approach is NASA climate scientist and activist James Hansen. Hansen has accused carbon markets of failing to rein in emissions and allowing “polluters and Wall Street traders to fleece the public out of billions of dollars.”

Hansen’s critique is more than grousing from the sidelines. Alongside groups such as the Citizens Climate Lobby in Canada, Hansen advocates an alternative approach to reducing emissions called fee and dividend. Although it remains a solution based on the market, fee and dividend takes a different tactic: rather than work to create new avenues for profit, it restricts markets, makes the fossil fuel sector less lucrative, and attempts to direct markets to meet human needs.

Unlike the cap and trade system, which is plagued by an opaque structure and dominated by bankers, industry insiders and technocrats, fee and dividend relies on a simple mechanism. It works by imposing a carbon fee directly at the point in which fossil fuels enter the economy: the port, the wellhead or the mineshaft. The collected fees are then distributed in their entirety to the population in the form of a monthly dividend. Everyone receives the same amount deposited directly into their bank account, regardless of income or assets.

The carbon fee would then increase each year, slowly making reliance on fossil fuels less and less economical, while driving incentive for green innovation. Since the increased cost of fossil fuels would then be passed along to consumers in the form of higher prices, the monthly dividend provides a cushion to compensate for higher heating and transportation costs.

The advantages of this system over cap and trade are clear and significant. It is simple and transparent, requires no new government bureaucracy, and does not create new opportunities for speculation. When coupled with the removal of all fossil fuel subsidies, it aims straight for the heart of the economic motor of climate change: cheap oil, gas and coal.

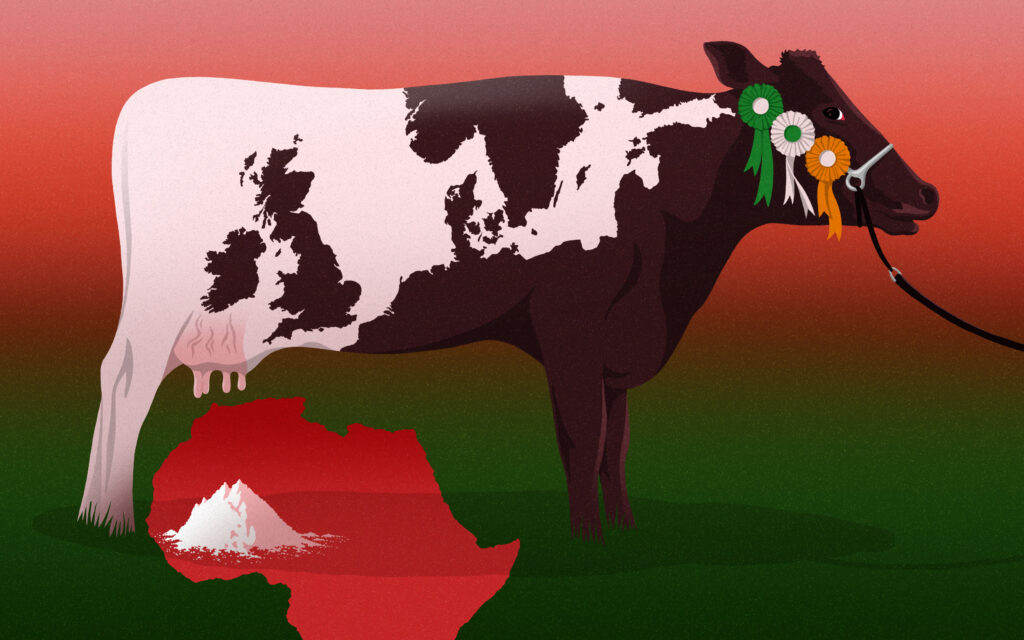

Crucially, fee and dividend also has a progressive dimension. According to a 2011 report by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA), the emissions of the top 1% of households are approximately three times the average, or six times greater than those of the bottom 10%. The report also shows that two-thirds of Canadians have average or below-average emission levels. Since every household receives the same size monthly carbon dividend, fee and dividend acts as a progressive income boost for lower-income, lower-emission groups. Plus, it provides an economic incentive for all Canadians to reduce their household emissions.

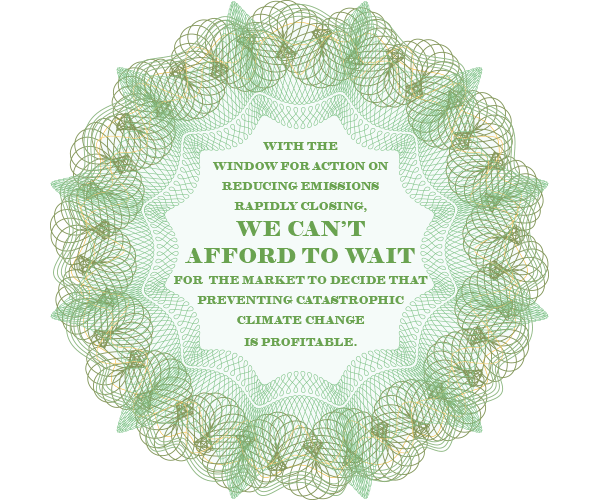

By ensuring that the costs of reducing emissions are largely borne by the enormously profitable fossil fuel companies themselves, fee and dividend provides an equitable and effective way forward. With the window for action on reducing emissions rapidly closing, we can’t afford to wait for the market to decide that preventing catastrophic climate change is profitable.

Art by Will Brown. All Rights Reserved.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts