It took a while for the Alabama public to understand that their state is being transformed into a tar sands Mecca. Proposals for rail and pipeline transport and tar sands storage facilities were first presented in 2010, and by 2012, most were rubber stamped with no public input.

But in 2013, a handful of concerned citizens in the Mobile Bay Sierra Club and the newly formed Tar Sands Mobile Coalition cried foul. And now their cries are being heard.

Two of four proposed projects are on hold – The Plains Southcap Pipeline, which would pass through the Big Creek Lake watershed that supplies drinking water to Mobile and the vicinity, and the American Tank & Vessel project to build tar sands storage tanks in Africatown, a historic Mobile neighborhood.

Still reeling from the BP oil spill, concerned citizens along the Gulf Coast are fighting back by educating themselves about the risks these tar sands projects present to their communities and then spreading the word to their neighbors, their elected officials and the media.

September 17th delivered a big victory when Judge Don Davis dismissed Plains Southcap’s condemnation lawsuit against Mobile Area Water and Sewer System (MAWSS). This victory opens the door for landowners to fight back. At issue was whether Plains Southcap had authority to use eminent domain to condemn the land they wanted in the Big Creek Watershed in the first place. This judge ruled they did not.

There are currently four tar sands related developments in progress in Mobile, Alabama:

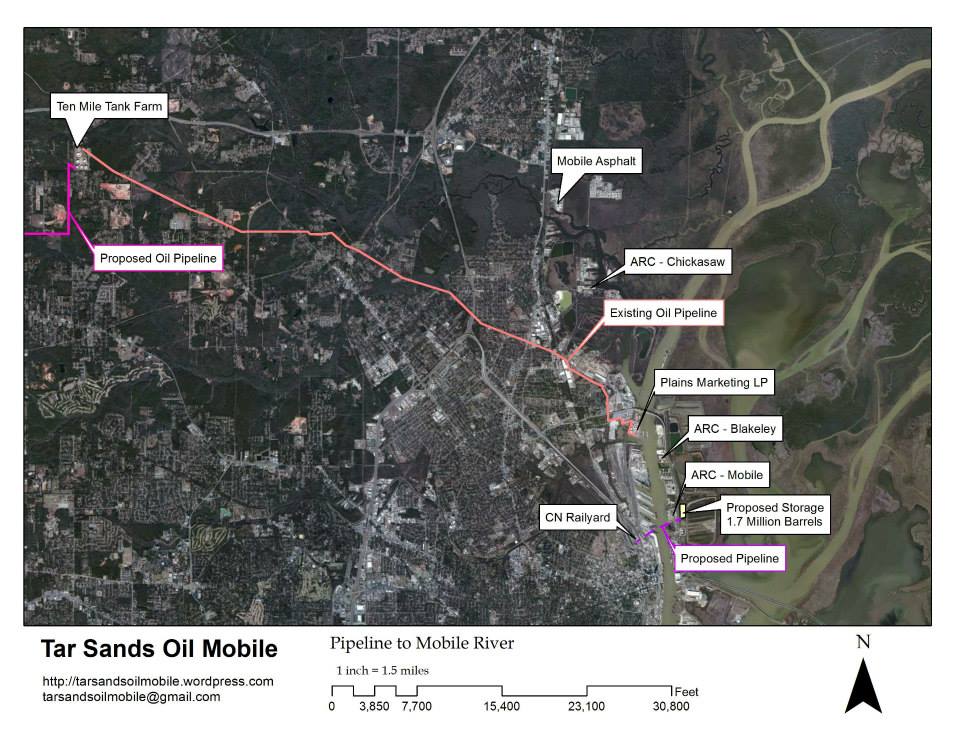

1. Arc Terminals and Canadian National are building a rail terminal in downtown Mobile. Canadian National is transporting heavy crude from Western Canada, known as tar sands bitumen, from Canada to Mobile via rail. The bitumen will be heated in order to get it on pressurized insulated cars that keep it warm, and then reheated to be able to get it off. The pressurized cars present worrying safety issues in the instance of derailment, and this process of transport uses a lot of energy.

2. Arc Terminals will build a pipeline to transport Canadian tar sands from the downtown rail terminal under the Mobile River to Arc’s storage tanks on nearby Blakely Island, where capacity will be greatly increased. Tar sands and other petroleum products gathered there could then be transported through an aging pipe, under historic Africatown to the Ten Mile Terminal where it will meet the Plains Southcap pipeline.

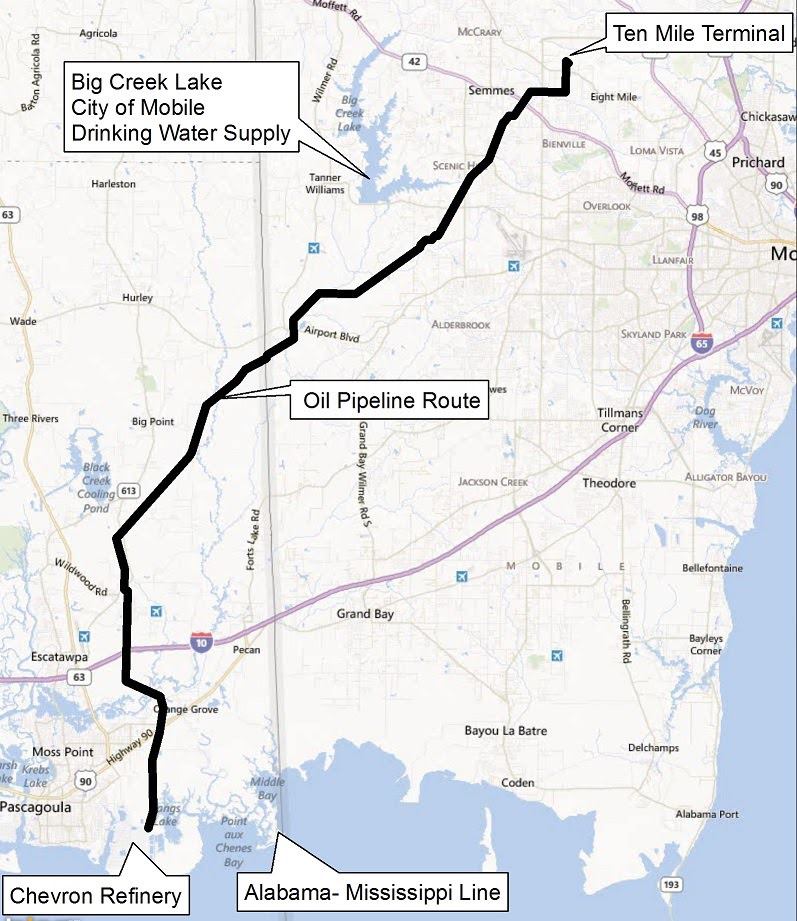

3. The Plains Southcap Pipeline will go from Ten Mile Terminal, Alabama to Pascagoula, Mississippi. Although Plains Southcap claims its pipeline will transport only conventional crude, and the Chevron refinery in Pascagoula claims it will not be processing tar sands, the infrastructure will be in place for them to accept tar sands crude should they choose to. The pipeline will be a high-capacity, 24-inch line able to move 150,000 barrels of product a day according to the Alabama Public Service Commission.

4. Storage tank expansion by American Tank & Vessel in Africatown will include tanks to hold tar sands and regular crude oil.

At a recent meeting attended by more than 200 people, Mobile mayor Samuel Jones said the Sierra Club knows more about these developments than he does.

He and Mobile County Commissioner Connie Hudson claim they were unaware of the Plains Southcap pipeline. It was approved after a 15-minute presentation by Plains Southcap at a meeting in Montgomery, AL held by the Alabama Public Service Commission on November 28th, 2011.

The only public announcements made about the meeting were four advertisements in local newspapers that omitted any mention of the key points of the project, including the pipeline’s route. At the hearings, Plains Southcap claimed the pipeline would lead to substantial job creation and domestic energy growth.

Factors like climate change and the resulting rising tides that will have a direct impact on the state’s coastline were ignored, and questions about environmental impact and insurance liability for such high-risk projects were not raised before the permit was issued.

Africatown resident Ruth Taylor Ballard says that being left in the dark on such matters is nothing new, unfortunately. The community hears about industrial projects when it is too late to do anything to stop them.

Alabama Governor Robert Bentley, who serves as chairman of the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission, defensively asserts that the Army Corps of Engineers–with input from both the Alabama Public Service Commission and the Alabama Department of Environmental Management– signed off on the project. Although he has some concerns about safety, he trusts industry to perform safely.

But Plains Southcap’s parent company, Houston-based Plains All American Pipeline (NYSE: PAA) has a far from spotless safety record.

The company’s spill record includes a 28,000 barrel oil spill on April 29, 2011 in Alberta, Canada, and the Bay Springs oil spill in Mississippi. The company recently agreed to a $44.25 Million settlement with the Environmental Protection Agency for violations from 10 other crude oil spills in the United States.

Plains Southcap’s pipeline is 70% complete, and Arc’s expansion on the riverfront has begun.

New storage tanks have already been built on Mobile’s riverfront. And a multitude of Canadian National’s black-painted railway cars move toxic heated bitumen though Africatown to downtown Mobile.

Trains with toxic cargo at downtown Mobile’s terminal

American Tank & Vessel is planning more storage tanks for Africatown, a couple of miles from downtown Mobile in an area zoned for industry. There is concern that existing pipeline in the area could be used to transport tar sands crude, if that is what industry demands.

Africatown was included on the National Register of Historic Places by the National Park Service on December 4, 2012. A core group of local elders fought to get this citation of the community’s historic importance, and hope it will help them in the fight to protect Africatown from tar sands threats.

Community activist Ariela Philip Scraig, 84, a life long resident of Africatown in Mobile, Alabama. She helped Africatown get on the National Register of Historic Places, and is now fighting against tar sands developments.

The Tar Sands Mobile Coalition’s actions are slowing down these projects. The Mobile Area Water and Sewer System (MAWSS) refused to give Plains Southcap permission to use its land in the watershed area despite the Army Corps of Engineers permit. Plains Southcap is suing MAWSS to condemn the land under eminent domain laws so they can move ahead.

They successfully argued that Plains Southcap, a limited liability corporation did not have the legal right to seek condemnation and asked that the case be dismissed. Plains Southcap can appeal or reroute the pipeline. Either way, the project is facing a major and costly delay.

Judy Hale, mayor of Semmes, a Mobile suburb, issued a stop work order when she found Plains Southcap had started construction before obtaining all the permits it needed and was not following state construction standards.

Federal Judge William Stelle upheld the stop work ruling against Plains Southcap, who challenged the order. Plains Southcap has said the delay is costing the company $124,000 a day.

Plains Southcap Pipeline in Semmes, Alabama where construction is at a standstill due to a stop work order.

During a recent meeting organized by the Tar Sands Mobile Coalition at the Mobile Bay Sierra Club, word spread that American Tank & Vessel had withdrawn its proposal to build more storage tanks in Africatown.

Despite this victory, the project can be resubmitted to the commission at any time.

“It’s like herpes,” said Dr. Rip Pfeiffer of Mobile, who gave a presentation at the meeting. “It’s not going to go away. It’s too much money and it will be back.”

Africatown’s Omar Smith points out that American Tank & Vessel withdrew its application because of a skipped step in the permitting process. With new public scrutiny of the project, it would have been turned down, meaning the company would have had to wait six months to resubmit. They are required to make a public presentation about the proposed new work to the impacted community before presenting it to the zoning board. Smith is sure they will try again after taking the proper steps.

Watch Omar Smith and Joe Womac talk about tar sands development in Africatown:

Plans for a new terminal on the Mobile River that would allow for greater quantities of Canadian tar sands crude to be delivered by train, a new pipeline to transport tar sands under the Mobile River, and more storage tanks dangerously close to Mobile’s downtown are all in the works.

The combination of toxic tar sands being stored and transported by rail and in pipelines, coupled with increased risk of mega storms due to climate change in an area already experiencing the effects of rising tides, makes these developments extremely risky.

Mobile Bay Sierra Club Conservation Chair David Underhill says,

“Imagine a hurricane storm surge 25 or 30 feet high, which is what happened with Katrina, coming up the bay and the river. This could result in the release of several times more petrochemicals into the environment than the Exxon Valdez, and even the Alabama Department of Environmental Management permit asks if the area is within a projected area of a so-called 100-year flood plain.”

Despite increasing public pressure, Governor Bentley continues to support all of these tar sands projects. He and Mississippi Governor Phil Bryant have teamed up to conduct a study on Hartselle sandstone, a natural underground resource that stretches from northern Alabama into northern Mississippi.

According to AL.com, “A recent study found an estimated 7.5 billion barrels of oil located in the reserves. Canada has proven to be a leader in oil sand recovery, and we hope through this evaluation process we can collaborate and share knowledge on best practices,” Bryant said.

Neither governor seems concerned with the dire environmental consequences a slew of recent tar sands and crude oil incidents are having, including the Enbridge Kalamazoo spill in Michigan that is still being cleaned up three years later at a cost of over a billion dollars; the Mayflower Pegasus pipeline spill in Arkansas where tar sands rushed down residential driveways, forcing evacuation of a housing development and contaminating nearby waterways; the ongoing tar sands leak at Canadian Natural Resources Ltd’s Cold Lake project in Northern Alberta, out of control since June, or the Lac Megantic train derailment that killed 47 people when runaway crude cars exploded in the city’s center.

In the meantime, local groups are making sure the word gets out. None of them wants to see Mobile become an environmental disaster zone.

Storage tanks on the banks of the Mobile River for Canadian tar sands, or other petroleum products.

Joe Walmac stands next to a historic marker for Africatown’s cemetery.

Train with toxic cargo passes by just a few feet from homes in Africatown.

Plains Southcap Pipeline on Airport Road in Alabama near the Mississippi state-line where construction is ongoing.

Dr. Rip Pfeiffer holds up a sign during a presentation he gave at a meeting held by the Mobile Bay Sierra Club and the Mobile Tar Sands Coalition.

Map of tar sand development projects in Mobile, Alabama.

Map of the Plains Southcap Pipeline.

All photos (c) Julie Dermansky.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts