In this DeSmog UK’s epic history post we take a look at how David Cameron’s rhetorical flourish beat down climate denier David Davis to win the Conservative Party leadership.

David Davis was among the few fantastically sceptic Conservative MPs and also one of the closest to the free-market think tank, the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) when, in 2005, he stood for leader of the party.

The then-shadow home secretary inspired hopes that the glory days of the Thatcher era were about to return to the crumbling Westminster offices of the IEA.

Tony Blair had just won an historic third term of the Labour party at the May elections and the defeated opposition leader Michael Howard knew that he would not survive long as the Tory leader.

‘Timeless’ Values

The following morning Howard announced a leadership election and that he would not be standing. Within a few days he had appointed George Osborne, the baby faced pretender, as shadow chancellor to Gordon Brown.

Davis decided to stand to defend the “timeless” values of the Conservatives including low taxation, the free market and “a suspicion of big government”. He was quickly touted as the bookmakers’ election favourite.

The MP was also lifelong friends with John Blundell, who at that time was still ensconced as director general at IEA headquarters on Lord North Street. Blundell would go on to forge close ties with Charles Koch and play a key role in bringing climate denial to Britain.

In one of his last interviews before he passed, Blundell told me: “We met when he [Davis] was Chair of London Business School Tory Club and I was chair at the London School of Economics. We met either at a regional meeting of Federation of Communication Services or its March 1972 Annual Conference.

“We discovered we had had the same flying instructor at Carlisle when he was doing some SAS Reserves related work and I was on an RAF Special Flying Award. He was my best man in 1977 and we are very close indeed.”

He added: “He is influential behind the scenes and in advising younger MPs on career strategy.”

Conservative Goals

But Davis was not competing alone. David Cameron, the 38-year-old Old Etonian, Oxford graduate and shadow education secretary, announced his intention to contend the leadership as a moderniser.

A smooth talking former television executive, Cameron gave a speech at the Policy Exchange think tank in June titled “We are all in it together” in which he argued that Conservative goals were “forward-looking, inclusive and generous” and that “we should never allow our opponents to caricature us as the opposite of these things… you never get anywhere by trashing your own brand”.

Davis and Cameron both officially announced they would stand as leader on 29 September 2005 with Davis calling from Westminster for “radical change” to “empower people and let them fulfil their potential.” An hour later Cameron was calling for his party to detoxify its brand.

Freak Weather

Climate change soon became an election issue after Britain experience an unusually hot October leading the extreme right wing Express newspaper to demand: “For God’s sake stop our freak weather”.

Cameron’s response was to visit the Eden Project in Cornwall where he demanded an end to the “Westminster party dogfight” and called for cross party political consensus. He also pledged to set up a national auditor to monitor carbon emissions and promised that under his Conservatives the climate would be a “priority” and not “an afterthought”.

He told the gathered journalists: “On the environment, I have set out today the steps we need to take to make this a cross party issue where we can agree things for the long term good of the country.”

Davis, on the other hand, all but ignored global warming as an election issue but remained the favourite for leader until the Conservative party conference where he delivered a “disastrous” speech and Cameron’s rhetorical flourish saw him rise to the top from an unpromising third.

New Era

On 6 December, Michael Spicer, the party chairman, declared that in the final round of the ballot Davis had received more than 64,000 votes but had fallen far short of Cameron’s 134,000 supporters. The defeat was a significant blow for the right of the party, and the few sceptics among them.

Cameron represented a new era of environmentalism, inclusivity and what, to some, was an uncomfortably accurate mimicking of Blair. Cameron’s climate calls meant the sceptics faced being left out in the political wilderness for years to come – and industry faced the government imposition of effective limits to carbon pollution for the first time.

His green rhetoric would prove particularly tough for one climate denying think tank, the International Policy Network, which had ties to Cameron’s ‘green guru’ and architect behind his campaign for Prime Minister.

Next time in the DeSmog UK epic history series we remember that moment when George W Bush declared: “America is addicted to oil.”

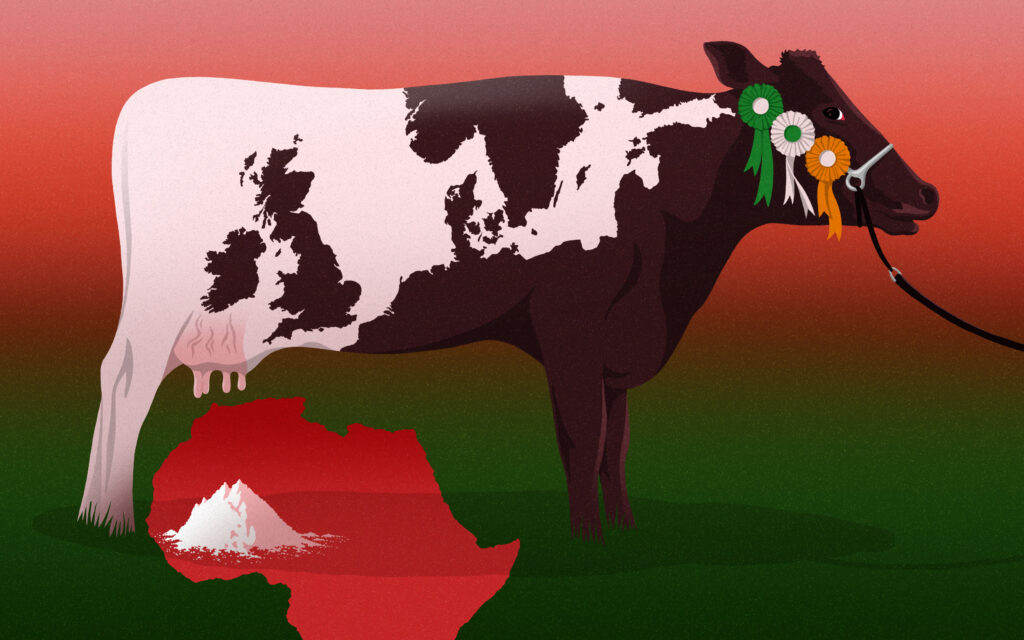

Photo: The Mirror via Creative Commons

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts