Harold Hamm isn’t the kind of guy you’d expect to be name dropping Ivy League schools. Born in Oklahoma, his education ended with his graduation from high school. Which didn’t stop him from becoming a multi-billionaire by building his own oil and gas fracking company, Continental Resources — a company that bills itself as “America’s Oil Champion.”

So for a self-made man from oil country, it wasn’t surprising to see a PowerPoint slide with the bullet points “Rigs, Rednecks, and Royalties” during his presentation this June at the annual Energy Information Administration conference in Washington, D.C. Although when he referred to the oil producing sections of the U.S. as “Cowboyistan” it didn’t get the laugh he was probably expecting.

What was a bit surprising was to see him touting the work of Columbia and Harvard to support his argument to lift the ban on exporting crude oil produced in the US.

“There have been a dozen studies so far, everyone of them come[sic] out with the same thing – lower gasoline prices….These are not folks who write about our industry all the time. We’re talking Columbia, we’re talking Harvard…”

Now, Hamm’s attempt to distance Columbia and Harvard from the oil industry was probably a clever tactic and not based on ignorance. Hamm has probably spent more time in D.C. this year than some members of Congress.

From the EIA conference to multiple appearances before congressional committees, Hamm has been pushing to get the oil export ban lifted.

Either way, he is wrong to say that Columbia and Harvard don’t write about the oil industry all of the time.

At Columbia University there is a rather new division of the school that does just that called the Center on Global Energy Policy (CGEP).

Center on Global Energy Policy (CGEP) School Thrives at Columbia

If you were looking for a success story in starting up a brand new group at your university and having it very quickly jump into a leading role in the national energy policy debate, Columbia’s CGEP represents the gold standard. On the surface the formula is pretty simple, although perhaps not easily replicated without some deep-pocketed funders.

First, get a high-level person with a White House pedigree to lead it. In this case the Center’s director Jason Bordoff, former special assistant to President Obama and senior director for energy and climate change on the staff of the National Security Council. Bordoff was hired to lead the Center from its inception a little over two years ago.

Next, line up powerful figures from the energy industry to join the group.

Like Daniel Yergin, about whom Time magazine said, “If there’s one man whose opinion matters more than any other on global energy markets, it’s Daniel Yergin.” Yergin is best known for his Pulitzer Prize winning book The Prize. It’s quite a coup to start up a brand new group and land the most influential man in global energy markets.

And if you want to be influential in the oil markets, it is always good to have someone like Robert McNally, George Bush’s former top energy advisor during the run up to the Iraq war.

Then put together a group of former high ranking government officials, military leaders, oil tanker brokers, investment bankers and oil company executives as advisors — a virtual dream team of influential people if your goal was to push the agenda of the oil and gas industry and influence policy.

What could possibly draw in so many heavy hitters to a brand new and unproven group?

While the CGEP website makes references to climate science, it becomes quite apparent after reviewing the list of advisors that they don’t appear to want any advice on climate science or renewable energy.

Since its inception, lifting the crude oil export ban has been a top priority of CGEP. In January, the center partnered with the Rhodium Group to issue a report called “Navigating the U.S. Oil Export Debate.” They have held star-studded panel discussions on the issue where every person on the panel agreed the ban should be lifted.

Jason Bordoff has testified in Congress about lifting the ban. Daniel Yergin has used his high profile to make pushing to end the ban his top priority for the past two years.

So when Harold Hamm says that we should all agree to lift the ban because of a report put out by Columbia — saying “these are not folks who write about our industry all the time” — he couldn’t be more wrong.

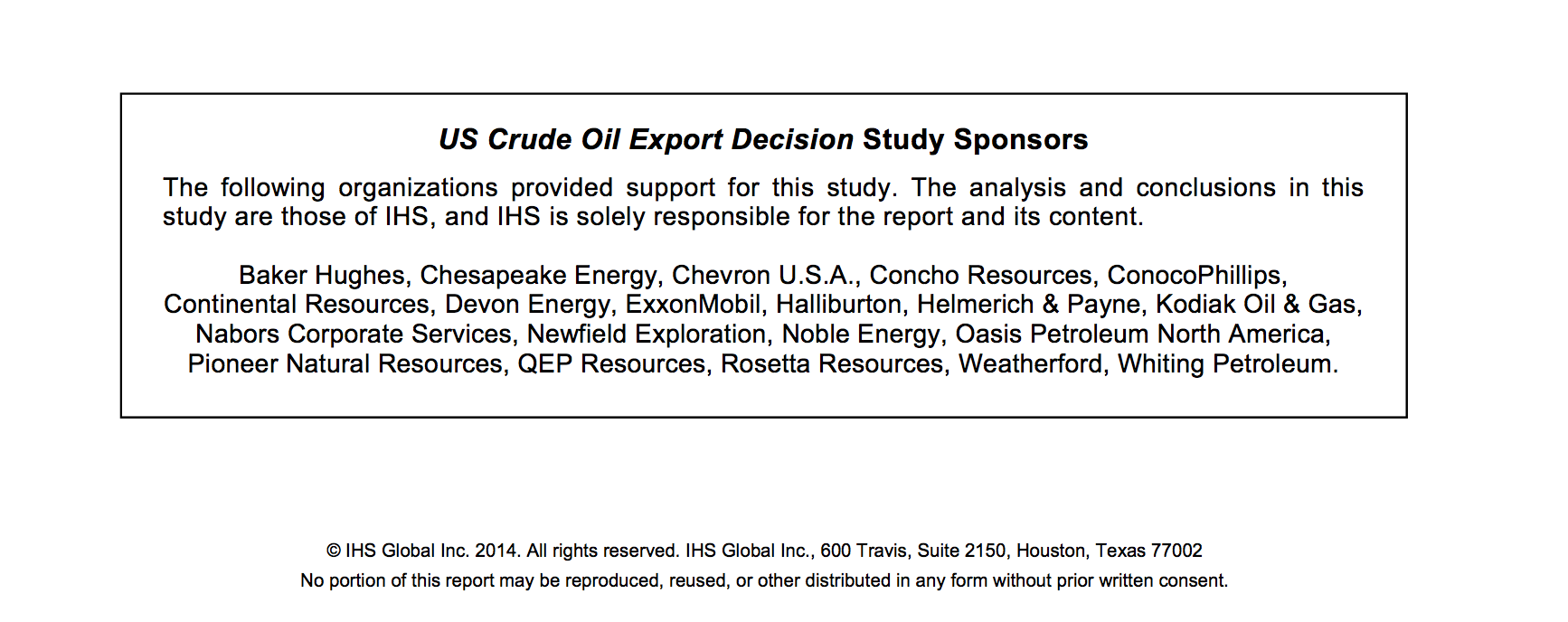

Most people associated with Columbia’s CGEP not only write and talk and create reports that are favorable to the oil industry all the time, many, like Daniel Yergin, work directly for companies that will profit from the lifting of the ban. However, Yergin’s association with these companies does conveniently fail to appear on the Columbia website.

Documents recently released via a Freedom of Information request by the Sightline Institute reveal how deeply involved Columbia’s CGEP is in the efforts to lift the oil export ban. The records reveal a paper trail of how an industry-funded report by Yergin via his employer IHS makes its way to the policy makers in government.

In a rather sparse email, Yergin forwards the new IHS study supporting lifting the ban to Bordoff.

The next day, Bordoff forwards the email and study to people at the U.S. Department of Commerce. The lack of content in Bordoff’s email seems to imply that all involved parties are well aware this study was on the way, and perhaps also that it would support lifting the ban.

Jason Bordoff goes as far as to write that he hasn’t even read the study “in detail.”

Was the study’s result, in favor of oil exports, a foregone conclusion?

A ConocoPhillips executive repeatedly cited this same IHS study — at Columbia’s annual energy symposium in 2014 — as a reason to lift the ban. She did not mention that Daniel Yergin authored it, even though he was the keynote speaker that day at the conference. She also failed to mention her company helped pay for the study.

So who is funding CGEP? We don’t know. Because Columbia is a private university and has no obligation to reveal its funding sources.

DeSmog’s Steve Horn recently sent repeated requests to CGEP and their public relations agency asking about their funding. They didn’t respond. But it does raise the question of why does a university policy group have a PR agency and who is paying for that?

Harvard’s Study to Lift the Oil Export Ban

When Harold Hamm was referring to Harvard he was referencing a report from the Harvard Business School called “America’s Unconventional Energy Opportunity” that recommends lifting the export ban. The report was done in conjunction with management consultants Boston Consulting Group, and the process of creating the report included an event where more than 80 industry leaders convened to discuss the issue.

People like Ken Cohen, Vice President of Public and Government Affairs for ExxonMobil, who blogged about attending the meeting and the resulting report.

In response to an inquiry about how the meeting and study were funded, a representative from Harvard Business School (HBS) explained to DeSmog via email that

“The effort is part of the U.S. Competitiveness Project at HBS (we at HBS do independent research as you know). BCG provided pro-bono, in-kind support and expertise to take on this complex topic.”

The report includes a conflict of interest disclaimer for Boston Consulting Group which basically informs the reader that there may be conflicts of interest but they aren’t going to reveal them. Now, what could possibly motivate BCG to work for free on something that advanced the interests of the oil industry?

Research by the Public Accountability Initiative notes that according to a 2012 tax return Boston Consulting Group was paid $648,875 by the Western States Petroleum Association for “advocacy” — although the nature of the actual work was not detailed. Although we don’t know if Boston Consulting Group considered its work on the Harvard study to be connected to its work for the Western States Petroleum Association, assisting with the Harvard report, whose conclusions are being used to influence the lifting of the crude oil export ban, certainly might qualify as advocacy.

One of the three authors of the report is Michael Porter, who has a background similar to Columbia’s Daniel Yergin. He is a widely praised author in the area of business competitiveness and is known for his book “On Competition.” Like Yergin he also had a second career outside of academia with a lucrative consulting firm he helped found, the Monitor Group.

However, as recently noted by DeSmog’s Steve Horn, after Monitor grew into a large international consultancy, it went out of business after it was revealed that it was working on a coordinated public relations effort to improve the image of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi.

What would motivate someone to work to improve Gaddafi’s image? As noted in a 2013 piece in the Boston Globe, if the efforts had been successful, “US oil companies would have hired Monitor to help them access Libya’s oil fields.”

If you are willing to work for Gaddafi to line your own pockets, it does raise the question of just where would you draw the line about pushing the oil industry’s agenda.

Harold Hamm’s Problem With Freedom of Information

The advantage of having this work done by private universities vs. public ones is that they are immune to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. Harold Hamm learned the part about public universities being accountable to the public the hard way when he reportedly tried to get University of Oklahoma researchers fired because they linked fracking to earthquakes.

A FOIA request by Bloomberg revealed an email from Larry Grillot, the dean of the university’s Mewbourne College of Earth and Energy informing colleagues that “Mr. Hamm is very upset at some of the earthquake reporting to the point that he would like to see select OGS staff dismissed.”

Hamm has given $20 million to the university, and perhaps expected some return on that investment.

Hamm also filed a $75,000 defamation lawsuit against the former head of the Oklahoma Independent Petroleum Association because of a Facebook post asserting that Hamm sought to “squelch” OGS work on the earthquakes issue.

A similar situation has recently been revealed at Kansas University where a Freedom of Information request revealed that the Koch brothers were literally funding the payroll of a lecturer who had testified before the state senate against the state’s renewable energy standards.

The New York Times also recently uncovered emails showing academics receiving money from Monsanto and working to push that company’s agenda. The email that probably summed up the situation best was from Dr. Kevin Folta of the University of Florida who wrote to a Monsanto executive promising results saying “I am grateful for this opportunity and promise a solid return on the investment.”

But the only reason we know this is because these are public universities. There is no way to get access to this information about private universities like Harvard and Columbia.

A Plan Comes Together

On the Columbia SIPA Center on Global Energy Policy website, they don’t try to hide their ambitions.

Mission: To improve the quality of energy policy and dialogue through objective, balanced, and rigorous analysis

Vision: To be among the world’s most respected, trusted and influential sources of energy policy analysis

“To be among the most influential sources of energy policy analysis.” A bold goal for an academic institution. But where boldness shades into worrisome is where an academic institution’s conclusions directly align with the American Petroleum Institute’s top priority of lifting the crude oil export ban.

Columbia appears well on the way to achieving its goals. However, its claims of being independent and objective will remain suspect at least until its sources of funding are revealed.

But since private institutions are immune to FOIA requests, the entities that paid to create this influential organization will remain secret. Mission accomplished.

Blog image: screen shot of Columbia Center on Global Energy Policy ‘Navigating the U.S. Oil Export Debate’ report cover.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts