This article is the first in a series by DeSmog on the safety of shipping ethanol and oil by rail.

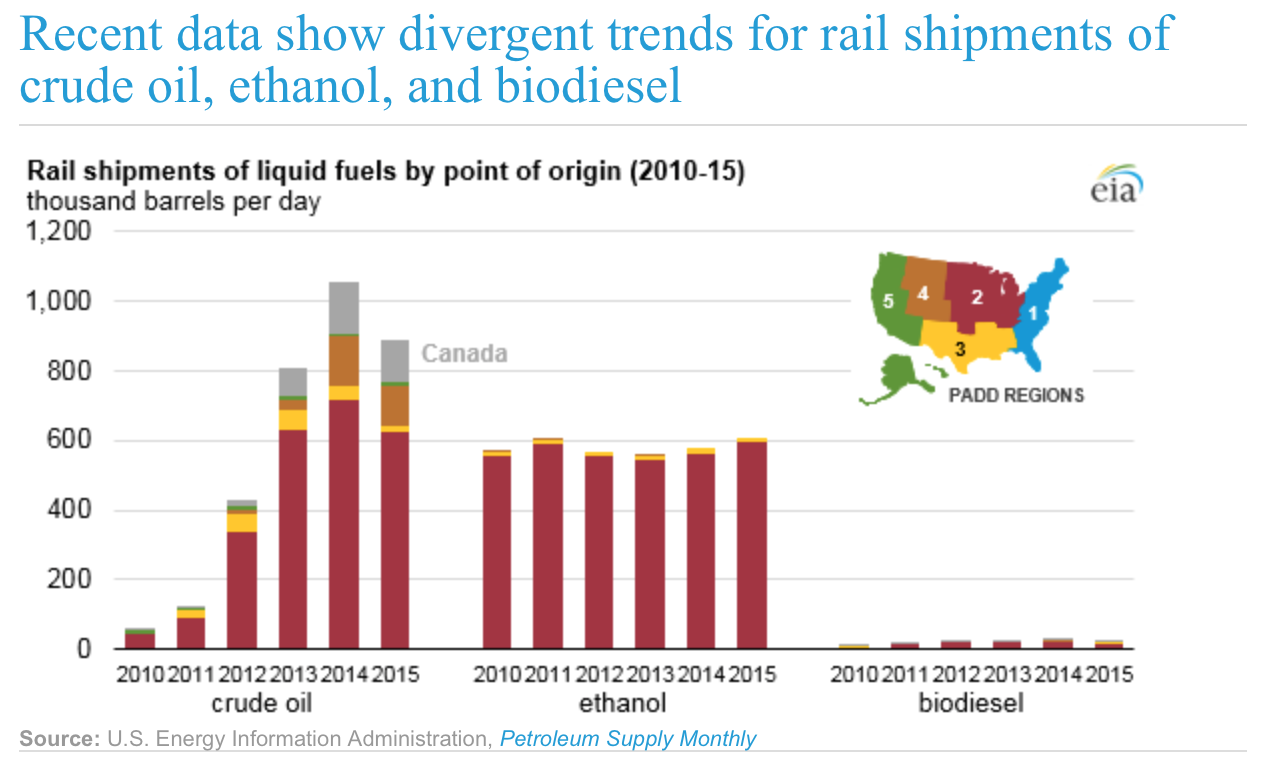

From 2010 to 2015, the total number of tank cars moving ethanol by rail was more than 1.98 million. That’s about 18 percent greater than the more than 1.68 million tank cars of crude oil shipped over the same time period.

With more ethanol than crude oil moved by rail in recent years, why isn’t anyone calling ethanol trains “bomb trains” too?

Ethanol is significantly less volatile than crude oil or gasoline. However, when an unpunctured rail car full of ethanol is engulfed in flames for long enough, it too will explode with the signature “bomb train mushroom cloud” typical of those carrying Bakken crude oil. For example, after a BNSF train derailed in Montana in August 2012, eight of the 14 cars carrying ethanol caught fire in what was described by a BNSF spokesperson as a “chain reaction,” which included a mushroom cloud–shaped ball of fire.

Yet perhaps the main reason no one is referring to ethanol trains as “bomb trains” is that these trains have been involved in fewer accidents — which is by far the best way to avoid large fires and explosions.

According to information provided to DeSmog by the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA), from 2010 to 2015 there were seven accidents involving ethanol train derailments; half as many as the 14 accidents with oil trains. This lower number of accidents for ethanol trains is despite the fact that more ethanol was moved by rail during the same six year period. So far, 2016 has seen one oil train accident but none involving ethanol.

Cynthia Quarterman used to be in charge of the U.S. Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, the federal agency that regulates oil and ethanol trains. After leaving that position, she made the following statement about oil train safety:

“Any hazmat regulator or investigator worth his salt would gather as much data as possible.”

However, to date, DeSmog is not aware of any discussion of the reason why oil trains derail more frequently than ethanol trains. Let’s take Quarterman’s advice and follow the data to determine possible explanations.

Despite Industry Claims, Oil Trains Derail More Often

As previously cited, the data on derailments certainly suggests oil trains are different — and more likely to derail — than ethanol trains.

Despite this, Dr. Christopher Barkan, an expert testifying in July 2016 for the rail industry on a proposed oil train facility in Vancouver, Washington, argued in his pre-trial testimony that this was not the case. [Prior to his current position as a professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Dr. Barkan worked for the Association of American Railroads (AAR), the rail industry’s biggest lobbying group.]

“Research on this topic is continuing, but the increased incidence of crude oil unit train derailments in recent years was more likely the result of the enormous (more than 40-fold) increase in petroleum crude oil traffic since 2009. The substantial growth in this traffic meant that these trains were exposed to greater potential involvement in accidents. There is no evidence that these trains were themselves inherently less safe than other types of trains, just that there were many more of them operating.”

However, this statement fails to acknowledge that while crude oil traffic has seen an “enormous increase” since 2009, more ethanol actually was transported by rail over that same period. When you further examine the data, evidence begins to appear that something about oil trains is making them “inherently less safe” than ethanol trains.

To improve safety, we need to answer the following question: Why aren’t ethanol trains derailing at the same rate as oil trains?

Longer Trains Are More Profitable — And Risky

One potential risk factor that stands out from rail crash data is that the oil trains that are derailing are long trains. Among the 15 oil train derailments since 2010, 10 were over 100 cars long and four were over 90 cars long. This fact by itself isn’t surprising; unit trains — those consisting solely of oil tank cars — are often longer than 100 cars.

On July 13, 2016, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) held a roundtable on the issue of tank car safety with regard to moving oil and ethanol by rail. During that event, Robert Fronczak of the Association of American Railroads (AAR) noted that crude oil is transported in unit trains “to a large degree” while, in contrast, “ethanol is generally not shipped in unit trains.”

At the same roundtable, Richard Kloster of rail consulting firm Alltranstek cited numbers showing unit trains of ethanol over 100 cars are extremely rare, with only 1 percent of ethanol moving this way.

He noted that 46 percent of ethanol was transported via trains of 75-99 cars. The rest — constituting more than half of all ethanol shipped by rail — traveled on trains of 74 or fewer cars. Furthermore, 32% of these ethanol shipments were actually single cars of ethanol transported as part of a mixed freight train.

Yet, of the seven ethanol train accidents between 2010 and 2015, three involved trains longer than 100 cars and two others included trains 98 cars long (although not all of them were unit trains carrying only ethanol). This means five of the seven recent ethanol train accidents occurred with the type of long trains typical of the more accident-prone oil trains.

Looking at this data, it is hard to argue with the fact that trains carrying oil are generally longer and derail with greater frequency than those carrying ethanol, which tend to be shorter. Most oil shipped by rail moves in these long unit trains. Most ethanol shipped by rail does not. When ethanol trains have derailed, however, most of them have been around 100 cars or more long.

Based on this information, DeSmog submitted the following question during the 2016 NTSB roundtable:

“Earlier it was noted only 1 percent of ethanol is shipped in unit trains of 100 cars. Most crude oil trains that have been involved in accidents are over 100 cars. Can the panel comment on train length as a potential risk factor? Could requiring shorter trains improve safety and keep more trains on the tracks?”

In response, the room sat in silence for a full 12 seconds. After no one from the rail industry volunteered to comment, Karl Alexy from FRA made a statement in which he changed the subject without directly answering the question.

At that point, Robert Fronczak from AAR made the classic industry argument that by making the trains shorter, more trains will be required to move the same amount of oil, therefore, potentially increasing the risk of derailment.

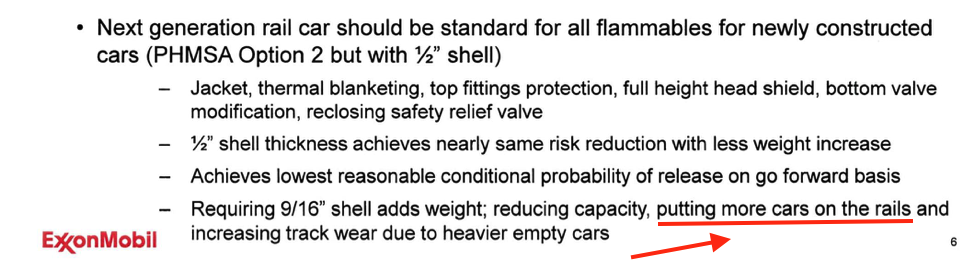

ExxonMobil and the oil industry use the same argument against improving rail safety by making tank car shells thicker: because that would mean more trains on the tracks. ExxonMobil presented the following slide to regulators, which argues against requiring safer, thicker tank cars.

What would be better, more safe trains or fewer unsafe trains? Seems like a question worth exploring, and it is clear that Fronczak is “not sure” about which actually produces safer results. Based on the response to DeSmog’s question (as visible in the above video), no one at either AAR or FRA appears interested in examinig the issue.

Judging by the long, awkward silence in a room full of the nation’s top rail experts, train length appears to be the proverbial “third rail” of train regulation. It’s the untouchable issue.

This “ignorance” approach is the other way bomb trains keep rolling. As long as industry representatives and regulators say they are never quite sure about the cause of or solution to an issue, they are forced to do nothing in the face of this uncertainty.

For example, regulators have not required the stabilization of Bakken crude oil to reduce its volatility prior to transport because they say “the science is still out” about how to do so most effectively. However, as explained in this DeSmog video, that is not the case. Still, the Department of Energy is now studying this issue and won’t have results until late 2017. Any regulations based on those findings would take several more years to complete.

And modern braking systems for trains are claimed to be an “unproven” technology, even though they been studied and proven to be safer than the current air braking systems on trains. The AAR even ran ads saying safety data didn’t support the use of modern braking systems. Congress has now mandated that train braking systems be studied further, again delaying any action.

Questioning known facts — or outright dismissing what is actually unknown, in the case of train length as a risk factor in derailments — is a very effective method for delaying action.

If longer trains do derail more often, perhaps they shouldn’t be allowed. As previously reported on DeSmog, no regulations exist for train length, and none are proposed.

As noted earlier, Dr. Barkan testified on behalf of the rail industry in support of the proposed Vancouver, Washington, oil-by-rail facility. Barkan is a professor of civil engineering at the University of Illinois with a focus on rail transportation and runs a research group that receives funding directly from the rail industry.

On the university website, Dr. Barkan notes the close relationship between the industry and his department: “Our strong relationship with the rail industry means our research has an impact and our graduates have great job opportunities.”

Robert Anderson, a student at the University of Illinois, completed his master’s thesis on the “Quantitative Analysis of Factors Affecting Railroad Accident Probability and Severity.” In the thesis he concludes the following:

“Thus, it follows that longer trains have an increased likelihood of having an accident due to a larger number of car-miles of exposure.

In 2001, the average number of cars per freight train of Class I freight railroads was 68.5 cars (AAR, 2003b). In the same year, the average length of derailed Class I freight trains was 78.6 cars (FRA, 2003a). These two statistics are consistent with the hypothesis that longer trains have a higher likelihood of derailment.

In light of the trade-off between car-mile and train-mile-caused derailments, there may be an optimal train length to minimize derailment occurrence.”

This research came from a university closely aligned with and funded by the rail industry and concludes that trains may have an optimal length to reduce their risk of derailment. Yet, regulators and industry have not acknowledged these results, and nothing is being done to address this issue.

According to the Association of American Railroads, in 2015 the average freight train length was 72.5 cars. In his testimony for the Vancouver oil-by-rail project, Dr. Barkan estimated the average train length for oil trains at that facility would be 118 cars, considerably longer than the average and in the range expected to derail more often than shorter trains.

Ethanol Expected to Start Using More Unit Trains

While the rail industry appears to have no interest in analyzing data to address the question of optimal train length, the ethanol and oil industry don’t seem against making data-driven decisions — at least when it comes to higher efficiency and higher profits. This point was made at the NTSB roundtable by Kelly Davis, director of regulatory affairs for the Renewable Fuels Association, an ethanol industry lobbying group:

“Unit trains has [sic] been an increasing transportation efficiency that we have been using … we are encouraged to do more unit trains.”

In late 2015, energy giant Kinder Morgan announced plans to build a new ethanol unit train facility in North Carolina.

Based on the ethanol industry’s interest in using more unit trains for “efficiency,” and the fact that it is allowed to transport ethanol in the unsafe DOT-111 tank cars until 2023, perhaps it won’t be long before ethanol trains are known as bomb trains too.

Make the Elephant Dance

Talking to the people who operate these trains makes clear that it is no easy task. Mile-long trains, ever-changing cargo, various braking systems, slack in the train, hills, curves, and fatigue are all part of the mix for train operators. They have to make a lot of judgment calls about how best to navigate the tracks with any given train.

Bill Keppen is a former locomotive engineer and comes from a railroad family. Keppen told DeSmog about his experience learning to operate long, heavy trains.

“Being the son of a respected engineer, I learned on the job from other good engineers,” Keppen said. “After a few years of experience, I felt like I could make the elephant dance.” Keppen was referring to the skills it take to successfully operate a big, heavy train.

Keppen also was clear that the longer the train, the harder it was to operate.

“It’s a matter of math and physics, the more cars you have, the more slack you’re going to have (between the cars in the train), more product movement you’re going to have … it’s just the way it is.”

Or, as he said, “It’s always easier to make the elephant dance if you have fewer cars than more cars.”

All of the evidence supports the idea that longer trains, which are more difficult to operate, are also more likely to derail. Yet instead of seeing research and regulations to identify the optimal train length for preventing derailments, what we get is the ethanol industry making the potentially dangerous move toward the use of more unit trains.

By examining data on ethanol trains, the oil-by-rail industry could learn a lot about how to ship this volatile product more safely. Yet the reality appears to be that the ethanol industry wants to emulate the oil-by-rail industry, not the other way around. And that is bad news for the 25 million people living in bomb train blast zones.

Main image credit: Ethanol unit train. By Justin Mikulka

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts