When Harvey’s rain, for the most part, stopped falling on August 30, I started making my way from Louisiana to Texas to document the pollution inevitably left in the storm’s path. That day I got as far as Vidor, a small town in southeast Texas where the floodwaters were still rising.

Getting there was no easy matter. I was forced to drive west in the eastbound lane of the interstate because the lanes I should have been driving in were flooded up to the top of the highway divider. All the while, I tried not to worry about the water rushing through cracks in the cement divider, which had the potential to give way.

Parts of Vidor were only accessible by boat or in a high-clearance vehicle. I hitched a ride in a monster truck, which pushed water over cars stuck in the floodwaters as we passed by a Mobil gas station, also submerged. I noted the irony considering ExxonMobil’s history of funding climate science denial and Harvey’s intensity tied to climate change.

Mobil gas station in Vidor, Texas, on August 31.

Home in Vidor, Texas, flooded up to its roof.

People navigating by boat in Vidor, Texas.

Louisiana’s Cajun Navy, a grassroots network of people with boats, along with other individuals with boats and trucks from across the country were on hand to help those who had initially chosen not to evacuate but changed their minds once the power was gone and the water continued to rise.

Houston After Harvey

When I arrived in Houston on September 1, I headed to one of the many subdivisions still under water on the city’s west side. There I met the Purcells, who were collecting what they could while water was rushing through their home. The neighborhood, made up of upscale homes, flooded during Harvey’s initial downpour when a nearby bayou overflowed. The flooding was compounded when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began releasing water from the Addicks Dam, which had already started to overflow.

Inside the Purcells’ home on the west side of Houston.

The Purcells rescuing whatever they can from their flooded house.

Lan Feng in her house on Gessner Road after the floodwaters receded on September 1.

Later I met the Fengs, whose nearby house was on dry ground. They were in the process of gutting it. While the initial rainstorm didn’t impact them, the water released from the Addicks Dam did. “We don’t have insurance,” Lan Feng told me. “Why would we? Our home isn’t in a flood zone.”

Hurricane Meets Fossil Fuel Industry

A couple of days later I joined Bryan Parras, the Sierra Club’s Beyond Dirty Fuels Gulf Coast organizer, and Kristal Ibarra-Rodriguez, an Austin-based volunteer coordinator with the Sierra Club. They were assessing the needs of underserved communities near oil and gas industry sites across the state’s coast.

“We are looking to identify partner organizations and collaborate in the near future to build and restore post-Harvey,” Rodriguez told me.

We stopped at a new housing development across from Houston’s Energy Corridor, a business district where many oil and gas companies have corporate offices and which was also flooded by the Addicks Dam release. The apartment building sits on a hill, and there was a line of oil along the grass indicating how high the water had risen, like a ring around a dirty bathtub. The water that remained in front of the housing units was too high for people to drive through, though it was starting to recede. Those who stayed told us they felt like they were on an island.

Bryan Parras and Kristal Ibarra-Rodriguez checking out a band of oil in front of the Heights at Park Row apartment building.

View of Houston’s Energy Corridor where BP and other oil and gas companies have offices across from The Heights at Park Row apartments.

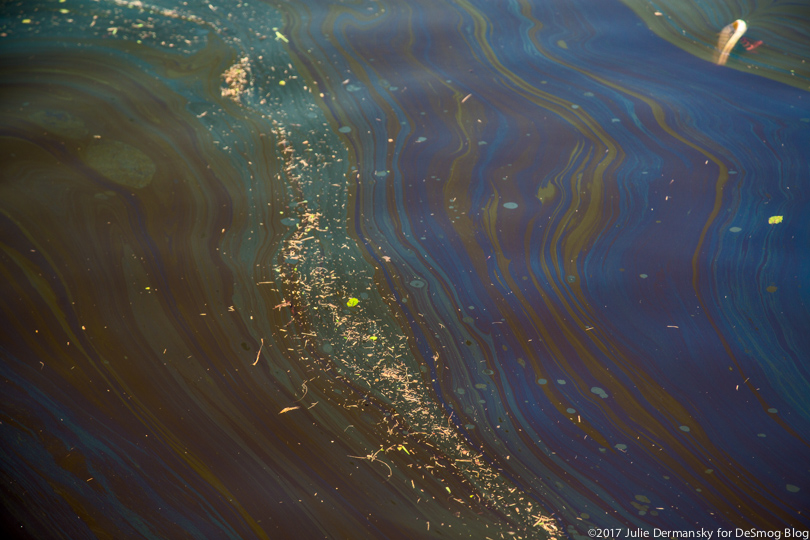

Oil in the floodwater left behind by Hurricane Harvey.

Parras pointed out the perfect vantage point for observing how unregulated development added to the current crisis. Construction cranes for a new development sat stuck in the floodwaters, and on the front of a glimmering office building, BP’s logo caught his eye.

Last year ProPublica and the Texas Tribune published a warning that showed, using interactive maps, how Houston’s unchecked development had left the city vulnerable to a major hurricane, risking a fate similar to New Orleans after Katrina. The article warned that rapid development coupled with more frequent and fierce rainstorms fueled by climate change could be disastrous for cities like Houston. Harvey proved the warning was spot on.

Communities and Their Refineries

Before heading back to Louisiana, I stopped in the Texas cities of Baytown, Beaumont, and Port Arthur, where some of the largest refineries in the United States remained shut down.

Jonathan Moraes, left with a flooded apartment and totaled car in Baytown, Texas, doesn’t know what he will do next.

“Man has been destroying nature so this is the outcome we are going to face,” Jonathan Moraes, a pipefitter from Mumbai, India, currently living in Baytown, told me. Baytown is just across the Houston Ship Channel, where Exxon’s largest U.S. refinery is located.

Moraes’s car and apartment flooded, leaving him and his wife trapped in their soggy rental unit. He was about to start a new job when Harvey hit but isn’t sure that job still exists at this point. Losing his car was a tough blow, because without it, he has no way to look for other work. Two days after his Baytown apartment flooded, he got word that his apartment on the other side of the world in Mumbai had also flooded. “If we can’t take care of nature, nature is going to backfire on us,” Moraes concluded. He showed me photos of his flooded Mumbai home, sent by his family, thinking that I might not believe him.

Exxon refinery in Beaumont, Texas trying to restart operations after Harvey.

An impassible bridge leads to a flooded pipe manufacturing shop in Beaumont, Texas.

In Beaumont, black smoke billowed out of an Exxon refinery. Near the refinery’s fence line, I spoke with Joseph Curtis, a freelance technician who does repairs at refineries. He was worried that his son’s asthma will get worse as the refineries start back up because they emit more hazardous compounds during this process.

He is right to worry. According to NBC, new regulatory filings submitted to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality state that, due to Hurricane Harvey, industry may have released as much as two million pounds of potentially hazardous airborne pollutants from oil refineries and other facilities in the Houston area.

Farther south in Port Arthur, I photographed standing water at both the Motiva and Valero refineries before I connected with environmentalist Hilton Kelley, who was returning home after evacuating. After he assessed the damage to his home and business, he began organizing relief efforts for his community.

Motiva’s refinery in Port Arthur shut down during Hurricane Harvey.

Oil tank at Valero’s refinery in Port Arthur surrounded by floodwater.

Containment boom attempts to confine an oil spill at Motiva’s refinery in Port Arthur.

Over the phone, Parras told me he would be visiting Kelley in Port Arthur soon and bringing some much-needed supplies.

“Getting aid to those impacted will be needed for years to come,” Parras said. Many of the communities abutting refineries impacted by the storm are already lacking in resources.

These neighborhoods have to deal with not only recovering from the obvious physical and emotional damage from the storm, but also an excess of potential pollutants released in the air, water, and soil.

By September 6, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality press release said it assessed 16 of the state’s 17 Superfund sites in the hurricane’s path, and was still in the process of restoring its air-monitoring network, shut down as the storm approached, leaving industry to self-report emissions.

“We know how well that works,” Parras said. He carries around his own respirator, but isn’t convinced it will protect him from the chemicals he may encounter. But he won’t let that stop him from helping affected communities.

Will Harvey force the state and federal government to change Houston’s lax regulations for building in potential flood zones? President Trump recently revoked an Obama-era directive that set flood-risk standards for federally funded infrastructure in areas affected by flooding and sea-level rise. This is a tell-tale sign that regulatory pressure won’t come from the federal government.

Meanwhile Hurricane Irma is taking aim at Florida.

All photos and video by Julie Dermansky.

Main image: Mobil gas station in Vidor, Texas.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts