By Tim Profeta, Duke University

“He was just doing his job.”

When I asked a longtime staffer to Sen. John McCain why the senator battled to address climate change in the early 2000s, that was his answer.

A simple answer, but one essential to understanding how McCain led those early efforts to combat the challenge when no one else would step forward.

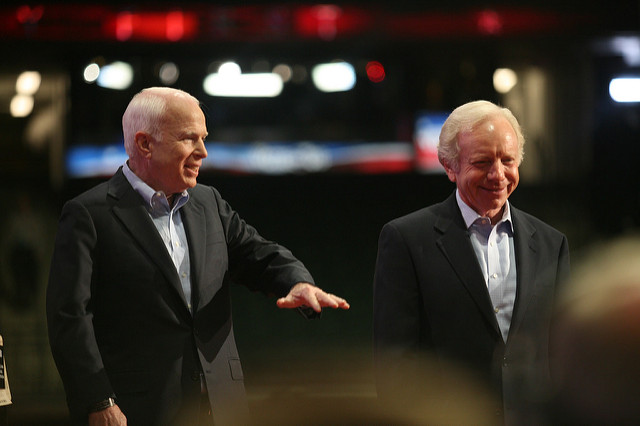

Although others had brought climate change as an issue to the Senate, McCain, a Republican, and democratic Sen. Joseph Lieberman were the first to bring climate legislation that aimed to reduce emissions. That attempt was their bipartisan 2003 Climate Stewardship Act. As Lieberman’s counsel for the environment, I helped write this legislation.

Science informed McCain’s policy

In 2000, McCain was the chair of the Senate Committee for Commerce, Science and Transportation, which had jurisdiction over the U.S. Global Climate Research Program. That program, established in 1990, aimed to assist “the Nation and the world to understand, assess, predict and respond to human-induced and natural processes of global change.”

McCain wanted to oversee the program’s activities and began a series of hearings on it. He sought out and gained insights from institutions he trusted in the hearings — including the U.S. Navy, McCain’s former professional home and a hub of defining research at the time — to learn more about climate science.

Armed with knowledge of the science, McCain proceeded to “do his job” to take on the challenge posed by climate change.

The hearings he called sparked conversations that led him to develop and co-sponsor, with Lieberman, the first legislation aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions by industries across the economy.

The legislation attempted to institute a market-based program to reduce emissions from electricity, manufacturing and transportation sectors of the economy. Those sectors represented 85 percent of U.S. emissions that at that time contributed to climate change.

This legislative step was particularly difficult for McCain as a Republican. Climate change legislation was, and remains, a tough political challenge as it requires regulating the sources of energy that underlie so much of our economy.

In 2000, the only recorded vote in the U.S. Senate on climate change was a 1997 resolution that passed unanimously. It was an effort to stop the U.S. from agreeing to what lawmakers believed to be unfavorable terms in the Kyoto Protocol.

Many key Republican constituencies were at the time particularly resistant to any form of greenhouse gas regulation.

As the senators began to pull together their proposal, building support for the bill required concessions to the political needs of certain senators. But for McCain, who had a history of bipartisan problem-solving, the only prodding he needed was the scientific evidence and his responsibility to respond to it.

Sens. Lindsey Graham, Susan Collins, John McCain and Hillary Rodham Clinton, on a fact-finding visit to Alaska in 2005 to see the effects of global warming. AP/Al Grillo

Advocating for their bill

Sens. McCain and Lieberman decided that the best way to change the politics of the issue was to force senators to become educated and accountable for their positions.

To do this, they drew on a political strategy that had worked before for them with their bipartisan campaign finance bill. They directed their staff to develop legislation in consultation with all political players and bring it to a vote as soon as possible. The support of a range of interests meant that politicians could more easily support the bill, and the quick vote was designed to force the senators to take a position.

The opportunity for a vote arose in mid-2003 as the Senate turned to comprehensive energy legislation. And in that effort, McCain’s tactical skill and resolve were on display.

The 2003 Senate debate about energy policy was the first major legislation that Majority Leader Bill Frist, a Tennessee Republican, managed. It represented an important effort to secure the new leader’s authority over his colleagues.

But it did not go well. The bill floundered on the floor. In order to get it passed, Frist engaged in legislative maneuvering that including asking for a rare thing, the Senate’s unanimous vote, or “consent,” to replace the energy legislation with the previous year’s bill that had passed the Senate. It was a legislative “Hail Mary.”

There are few moments of true political leverage in the Senate like a “must pass” request for unanimous consent. The only way for Frist to achieve it was for all 100 senators to sign off. That meant each senator had the power to stop the bill.

McCain recognized this moment of political leverage and seized it to advance the 2003 climate change legislation. He and Lieberman would say no to Frist’s request for unanimous consent, unless Frist would allow a vote on their bill.

After I informed the Senate leadership that McCain and Lieberman might have an objection, I sprinted to the staff phones and called McCain’s office – a Republican was better for holding a bill being managed by a Republican.

Within minutes, McCain was on the floor of the Senate, demanding that his climate bill be scheduled for a vote before anything could move forward. His request was granted, and Sen. Frist promised an up-or-down vote on the bill before the end of the year.

By resisting the political pressure from his own majority leader, Sen. McCain demonstrated his political spine. And in doing so, he showed his tactical skill, negotiating a commitment for a recorded vote on the final passage of the climate bill.

One hundred senators would have to publicly state their position on climate change.

Recharging the climate debate

Three months later, McCain and Lieberman brought their legislation to the floor and secured 43 votes in favor, plus the pledge of support from absent Sen. John Edwards.

It was a loss, but still important as the first step in the McCain-Lieberman strategy to get lawmakers to declare where they stood on climate change.

Forty-four senators were now on the record favoring the bill, and the remaining 56 could be held politically accountable. And it was a far cry from the 95-0 vote count against the Kyoto climate change treaty from 1997 that stood previously as a litmus test on the issue.

Despite its failure to pass, the McCain-Lieberman bill breathed life into legislative efforts to respond to climate change.

McCain at a campaign rally in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, on Jan. 7, 2008, during his presidential bid. AP/Charles Dharapak

The momentum for climate legislation built through the decade, with the development of the 2005 and 2007 Climate Stewardship Innovation Acts, neither of which passed. The 2008 presidential race was significant in that both candidates, Sens. McCain and Obama, supported serious climate change measures.

With President Obama’s election, it looked like 2009 marked the moment the nation would finally address climate change concretely. But a combination of political polarization, leadership failures and economic recession conspired to frustrate the climate legislation of 2009-2010.

Since the 2010 midterm elections, climate legislation has not re-emerged.

As a result, we now have arrived at a point not unlike 2001, with political paralysis on Capitol Hill on the issue of climate change. Right now, there is no clear legislative leader who, like McCain, will step up and tackle such a politically risky problem. Perhaps we’ll get the chance to see another bipartisan leader emerge.

by Tim Profeta, Director, Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions and Associate Professor of Practice, Duke University

Originally published by The Conversation

Image credit: Senators John McCain and Joe Lieberman via PBS NewsHour, Flickr CC

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts