When someone charges a cellphone or flips on the lights, what costs are felt by the far-off communities that produced the coal or gas powering that home? What happens to those same communities when a utility decides to switch from coal power to natural gas? And what keeps these impacts of American energy habits hidden from view?

New research helps provide some clarity. A study led by Noel Healy from Salem State University in Massachusetts analyzes the hidden but interconnected injustices that can occur throughout the world’s fossil fuel supply chains.

The research project spanned three sites: a power plant in Salem, Massachusetts, recently decommissioned and converted from coal-fired to natural gas; the Cerrejón open-pit coal mine in La Guajira, Colombia, which was the primary coal supplier to the Salem plant for over a decade; and hydraulic fracturing (fracking) sites in Pennsylvania, which now supply natural gas to the power plant in Salem.

A Coal Mine’s Impacts

Healy and his colleagues Jennie Stephens from Northeastern University and Stephanie Malin from Colorado State University reveal what they call “interlinked chains of injustices,” or how local energy decision-making in one region generates social and environmental injustices in other, distant ones.

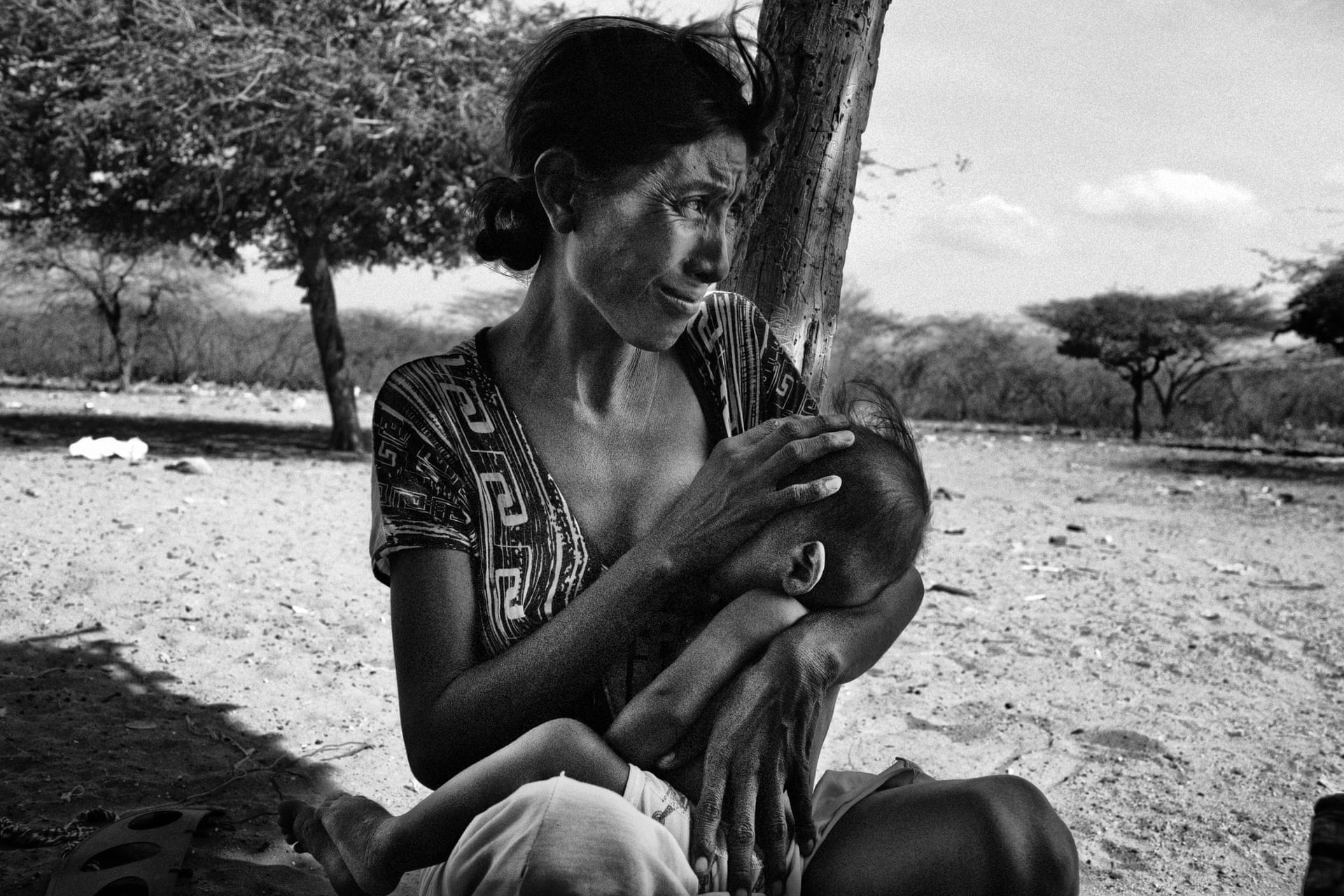

Reliance on coal mining in La Guajira to turn on the lights in Massachusetts supported a mine that over more than three decades has forcibly displaced several nearby indigenous communities and tried to suppress, with bloody results, union activity. The mine’s operations have been linked to widespread pollution from coal dust and the destruction of fishing and hunting grounds, leaving La Guajira plagued by food insecurity.

“Some villages were bulldozed, communities forcibly removed, like the Afro-Colombian community of Tabaco,” said Healy, who has conducted research surrounding the Cerrejón mine. “Others were displaced via the ‘slow violence’ of contaminated farmland and drinking water.”

The Cerrejón mine in La Guajira, Colombia, is one of the largest open-pit coal mines in the world. Credit: Noel Healy, used with permission

“Communities live in fear,” he added. “We witnessed high levels of community trauma, anxiety, and stress.” In the communities Healy interviewed, children reportedly suffer from respiratory illnesses and some people are afraid to drink the water.

“Mining operations have destroyed the social and cultural fabric of communities within the region, traditional migration routes have been cut off, and communities lost access to sacred sites and ancestral grounds,” Healy said.

Colombian Coal to New England Power

Aviva Chomsky, a Salem resident, professor, and activist, has long fought to bring attention to the injustices surrounding the Colombian mine by making them more visible to its end users in New England.

“Most of us like to think of ourselves as good people who would not deliberately harm someone or take advantage of someone,” Chomsky told DeSmog. “Yet we are the beneficiaries of a system that harms and takes advantage of a lot of people — and we collaborate with it because we are able to not see the harms.”

Chomsky is the founder of the North Shore Colombia Solidarity Committee (NSCSC) and has organized speaking tours for several of La Guajira’s indigenous leaders and activists in Massachusetts.

Antonia is an indigenous Wayúu mother. The Cercado Dam drained the Rancheria River, her community’s only nearby source of water. According to Noel Healy, the Cerrejón mine uses over 4.4 million gallons of water a day. Credit: Nicolò Filippo Rosso, used with permission

“We need to hear the voices of the people displaced and the lives and livelihoods destroyed by coal,” said Chomsky. “In La Guajira, Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities are crying out for the world to see what is happening to them and to support their struggle for recognition and reparations from the coal company that has destroyed their farming communities and left them dispossessed.”

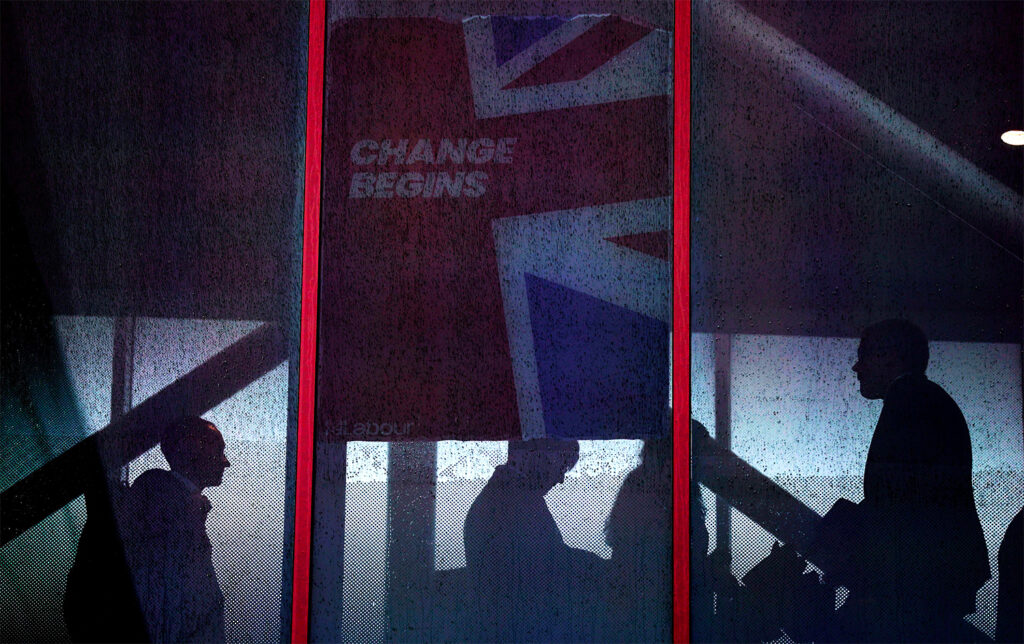

And while activist pressure has led local political leaders in Salem to acknowledge the injustices wrought by the reliance on coal, there’s a reluctance to extend the same recognition to the effects from Pennsylvania’s fracking fields, where Salem’s power plant now sources its energy feedstock.

‘An economic logic that allows some places to be destroyed’

The study led by Healy has found that energy injustices in one place are perpetuated in another when regulators fail to account for them. For example, the extraction, processing, and transportation of natural gas to Salem were not considered in the formal siting process when the power plant made the switch from coal.

The devastation in these zones is “often shielded by the absence of effective regulatory frameworks, and is normalized by an economic logic that allows some places to be destroyed in the name of progress, profit, and national and regional economic interests,” Healy and his colleagues wrote.

Just as troubling, the researchers found that companies involved in the supply chain perform what amounts to greenwashing these injustices in order to justify their operations. The current owners of the Cerrejón mine rebranded the mine as “Cerrejón Minería responsable” (responsible mining), and launched a system of charitable foundations to complement its corporate social responsibility division.

The Cerrejón open-pit coal mine was rebranded as “Minería responsable,” or “responsible mining.” Credit: Noel Healy, used with permission

In Salem, the new owners of the natural gas-fired plant downplayed the dangers of fracking by claiming that form of extraction can be done safely under appropriate regulations.

Chomsky echoes these findings: “It takes a lot of work to see these injustices since they are deliberately hidden from us. Coal companies and energy companies make great profit off of a system that depends on our complicity. We enjoy cheap electricity — and we don’t have to see the destruction caused by the extraction of the coal.”

As in the case of the Colombian coal mine, it is mainly up to local activists at the site of consumption to make the injustices at the point of extraction visible to the end consumers. Recently, several Massachusetts organizations, including Mothers Out Front and Clean Water Actions, organized a speaking tour by four Pennsylvania activists impacted by fracking.

For many Massachusetts residents, it was their first exposure to such harrowing tales of schools suffering from benzene pollution; farmlands decimated by drilling wells, trucking, and fracking fluids; and drilling leases gone awry.

An Energy Disconnect

As energy production has increasingly shifted across borders, so too has the disconnect between places of energy consumption and those of energy production.

“There is a clear ‘consumer blindness’ and citizens and residents are often unaware of where the fuel they consume is coming from and what injustices were inflicted on communities within those sites of fossil fuel extraction,” said Healy. “Exposing these injustices of energy ‘sacrifice zones’ — like in La Guajira or Pennsylvania — could be critical for future energy policy decision-making.”

He suggested energy consumers team up with climate and human rights groups. Together, he said, they can call on policymakers to recognize the impacts along a particular energy supply chain when regulators fail to do so.

Reaching the Paris Agreement’s goals for limiting climate change, however, also means getting off coal and risks perpetuating some of the same injustices as other energy transitions. Healy said the Colombian government should establish plans for what is known as a “just transition” — ensuring environmental sustainability along with social and economic justice — for the department of La Guajira.

“Otherwise if the mine shuts down tomorrow, a whole region will become stranded,” said Healy.

He pointed to Spain’s plans for shuttering its coal industry.

“They included early-retirement schemes for miners over 48, environmental restoration in pit communities and re-skilling schemes for new green industries,” he said before proposing who should finance such a transition. “The close relationship between Cerrejón and elected officials meant the mine reaped the benefits of favorable tax breaks. It is clear that Cerrejón has benefited most from decades of coal extraction, and it is Cerrejón who should be held accountable for reparations for all the damages caused to the region.”

Editor’s note 11/16/18, 12:03 p.m. PST: This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Noel Healy’s name. We regret the error.

Main image: A Wayúu woman makes soup in 2016. According to the Wayúu, the Cerrejón coal mine uses much of the region’s scarce water, diverting and contaminating the water they need to drink and irrigate their subsistence crops. Credit: Nicolò Filippo Rosso, used with permission

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts