Congressional Democrats have introduced a “Green New Deal” proposal that calls for a 10-year national mobilization to curb climate change by shifting the U.S. economy away from fossil fuels. Many progressives support this idea, while skeptics argue that a decade is not long enough to remake our nation’s energy system.

The closest analog to this effort occurred in 2009, when President Obama and Congress worked together to combat a severe economic recession by passing a massive economic stimulus plan. Among its many provisions, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 provided US$90 billion to promote clean energy. The bil’s clean energy package, which was dubbed the “biggest energy bill in history,” laid the foundation for dramatic changes to the energy system over the last 10 years.

I am an environmental economist and worked with Congress as a member of the Obama presidential transition team to negotiate the energy package. Then I oversaw its implementation as a White House official in 2009-2010. Based on my experience, I believe this effort holds several key lessons for a Green New Deal and other policies the new Congress will consider.

A Lower-Carbon Economy

The 2009 Recovery Act focused on four major categories of energy-related investments: Energy efficiency, the electric grid, transportation and clean energy. Major targets included about $25 billion to promote renewable electricity generation through investment grants, production tax credits and loan guarantees. Another $20 billion funded energy efficiency and conservation through tax credits, rebates and block grants to state and local governments.

About $10 billion supported investments in smart electric meter and smart grid technology and long-distance transmission lines. The bill provided $5 billion for advanced vehicle technologies, such as electric battery manufacturing subsidies and heavy-duty diesel retrofits. It also included $2 billion to develop carbon capture and storage technologies for coal-fired power plants.

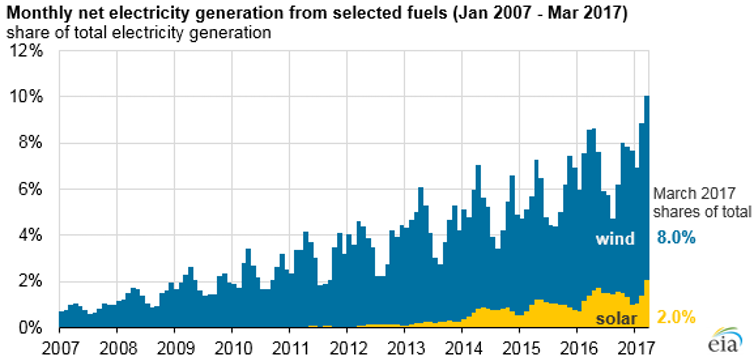

These investments catalyzed rapid growth in renewable power. Since 2008, wind power has more than tripled and solar power has increased 80-fold. This wind and solar investment significantly outpaced new investment in natural gas power plants over the past decade.

The largest years of wind power investment occurred in 2009 and 2012 – the first and last years of Recovery Act support. More recent growth in solar across the country, as utilities and homeowners alike have adopted it, reflects significant drops in the cost of solar panels, which were enabled by generous investment subsidies in previous years.

This renewable energy surge has played a key role in cutting carbon dioxide emissions from the U.S. electric power sector by 28 percent since 2005. In 2017, renewable power and power from cheap natural gas were nearly equally responsible for these emission reductions.

Even though the U.S. population has grown about 8 percent and our nation’s gross domestic product has risen more than 20 percent since 2008, residential electricity consumption was lower in 2017 than in 2008. This decrease reflects long-term energy savings benefits from Recovery Act investments in high-performance windows, insulation, high-efficiency furnaces and water heaters and advanced lighting. Electric vehicles make up a growing share of the U.S. car market which was aided by Recovery Act investments in advanced battery manufacturing facilities.

High-profile Setbacks

Not all programs yielded such impressive returns. Although the federal government invested $2 billion in FutureGen, a decade-long effort to capture carbon dioxide emissions from coal-fired power plants and store them underground, this effort failed to attract enough cost-matching investments from private utilities. As a result, it never moved forward to test carbon capture and storage at commercial scale.

The Department of Energy Loan Guarantee Program awarded about $2 billion to guarantee $16 billion in loans at 25 companies investing in solar, wind and geothermal power and clean energy manufacturing projects. It produced a small pipeline of innovative energy projects and imposed burdensome requirements that undermined its effectiveness. Ultimately the program became a political liability when Solyndra, a solar panel manufacturer, defaulted on a federally guaranteed $535 million loan.

Lessons for a Green New Deal

This record offers valuable lessons for policymakers who want to catalyze further progress toward a clean energy economy. Critically, the main reason to spend public money in the energy sector is to drive changes in investment. Businesses already have plenty of incentive to invest in energy; the challenge is getting them to invest in socially preferred areas, such as lower-carbon energy sources.

Taxpayer dollars are limited, so well-designed policies should deliver results at the lowest possible cost. The Obama administration needed to implement the Recovery Act quickly in 2009 because the economy was in a tailspin, so some energy stimulus programs failed this test by awarding subsidies that didn’t do much to change household and business energy choices (although they delivered economic stimulus). For example, about 90 percent of families that received rebates for buying EnergyStar-rated refrigerators likely would have done so without the Recovery Act appliance rebate program.

Another key lesson is that when policies are designed to be simple and transparent, it is easier for businesses and households to understand them. Complex, opaque processes create opportunities for crony capitalism that may undermine program goals and attract political criticism. Solyndra’s default led to a four-year federal investigation and charges of political favoritism in awarding the loan guarantee.

Today, with the emergence of big data and advances in analytical methods, managers can design and implement programs in ways that make it easier to measure their performance. Designing such reviews at the start would facilitate low-cost evaluation after programs go into effect. The need for speed during the Great Recession precluded such planning, but the next stage of clean energy policies can be designed to enable this kind of learning, which can then inform thoughtful policy updates and reforms.

Finally, the Obama administration saw government spending on clean energy as a complement and stepping stone for a more ambitious, economy-wide carbon pricing policy. In 2009 President Obama supported a cap-and-trade program to cover America’s carbon dioxide emissions. More recently, some experts have called for carbon taxes to drive deep, cost-effective greenhouse gas emission reductions.

Just as we economists believed in 2009 that an economy-wide market-based approach would be the most effective way to combat climate change, it still holds true today. The Green New Deal resolution does not address carbon pricing, but I believe that an ambitious carbon tax could promote broad and deep economy-wide emission reductions today and the far-reaching innovation necessary to transform the energy foundation of the U.S. economy.

Joseph Aldy is Associate Professor of Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Main image: Assembling capacitors for electric automobiles at SBE, Inc. in Barre, Vermont, July 16, 2010. SBE received a $9 million stimulus grant to build electric drive components. Credit: AP Photo/Toby Talbot

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts