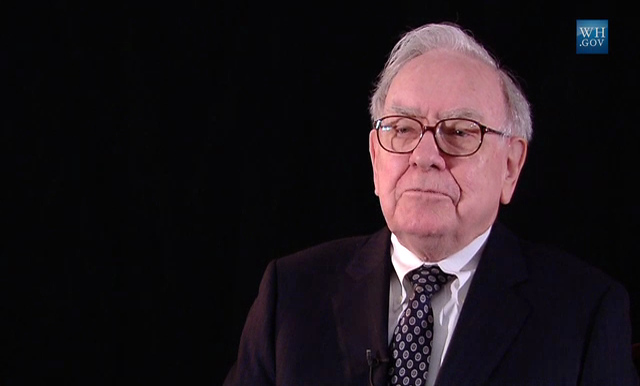

Warren Buffett, CEO of investment holding company Berkshire Hathaway, is considered one of the top investors in history and can back up that track record with a personal wealth of around $90 billion. Buffett is known for advising investors to be “fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful.”

In the U.S. fracked oil industry, this month can be read like a textbook version of Buffett’s fear and greed adage. The shale industry showed plenty of signs of fear while Buffett made a massive “greedy” bet on the future of the Permian Shale in Texas and New Mexico, assuming it will produce oil profitably and investing $10 billion in Occidental’s purchase of shale producer Anadarko.

Buffett is betting on a fracked oil future as climate scientists warn of the waning window for preventing catastrophic climate change and fund managers and energy researchers warn of stranded oil and gas assets.

Déjà Vu?

Meanwhile, on May 1 Houston-based energy investment group Tudor, Pickering, and Holt released an investment note about the U.S. shale industry titled, “Don’t Raise Your Budget,” and imploring shale oil producers to stop spending more money than they make selling oil.

If that feels like déjà vu, it should. In 2018, The Wall Street Journal reported the same message from investors asking for fiscal restraint alongside predictions of 2018 finally being a profitable year for the shale oil industry. As one analyst said, “Is this time going to be different? I think yes, a little bit.”

But was it different? In a word, no.

Now Tudor Pickering is begging the industry to listen and stop overspending. It’s literally saying, “Please, for the love of God, don’t do it.”

This trend has led to a well-known short seller recently describing overspending shale oil companies as “capital destruction machines.”

A short seller calls U.S. shale companies “capital destruction machines” and bets it all on a spectacular market crash https://t.co/IAZR3JKiFe via @markets #OOTT

— Kevin Orland (@kevinorland) May 10, 2019

Capital Destruction Machines

Last year DeSmog featured the company Halcón Resources as an example of how shale oil company executives get rich while losing investor money. Halcón Resources had emerged from bankruptcy and promised success with the currently popular strategy of focusing solely on oil production in the Permian region.

After last year’s first quarter financial results, investment site The Motley Fool wrote the following about Halcón’s plans:

“Halcón Resources has an aggressive plan to increase output at a lightning-fast rate, to offset asset sales in recent years. It’s a big bet on higher oil prices, since the company is significantly outspending cash flow to get up to where it wants to be as fast as possible.”

To which we asked, “Anyone want to bet how this ends up?”

After another year of producing in the Permian, Halcón has not delivered and Kallendish Energy reports the shale company is now developing “new strategic and financial plans.” Why?

Well, Halcón lost another $336.6 million in the first quarter of 2019. Its stock lost over 50 percent of its value last week and is now in penny stock range. But its executives still get paid.

While the Permian wasn’t the solution for Halcón, the region is where the U.S. fracked oil industry is still pinning its hopes for finally unlocking profits. As we recently noted, Exxon and Chevron have both made fracked oil production in the Permian a central part of their business strategies.

Exxon appears to have adopted the shale oil mentality already. According to Bloomberg, “Exxon will likely continue to outspend its organic cash from operations, as it seeks to rebuild its growth portfolio.”

Permian oil producer Pioneer Resources has also been in the news recently. In February, after its financial results showed it “could not generate enough cash flows to fully fund its capital expenditure,” Pioneer’s CEO suddenly retired and the former CEO Scott Sheffield returned to run the company.

One of Sheffield’s claims to fame is that in 2016 he said Permian oil could be produced profitably when oil prices were below $30 a barrel. Apparently he was very wrong.

Oil and gas drilling (fracking, hydraulic fracturing) pads at Wickett, Texas. Credit: Dennis Dimick, CC BY–NC–ND 2.0

Sheffield has just overseen a round of layoffs and a recent stunning asset sale. In February 2018, Pioneer announced its intention to focus just on the Permian (like Halcón) and thus would be selling its assets in the Eagle Ford shale play in Texas. Initial estimates were that the assets were worth $2 billion. This past April, however, Reuters reported the price would now likely be less than $1 billion.

The deal was finalized at $25 million, with future payments based on the price of oil and gas and potentially adding up to $475 million. But those Eagle Ford shale assets sold for only $25 million up front. Capital destruction in action.

Bakken oil producer Whiting Petroleum also reported losses when profits were expected.

And it isn’t just the oil producers who are suffering. The oil service companies who do much of the actual work producing the oil have not been faring well either.

In February the CEO of cash-shedding oil services company Weatherford International Plc was asked if he was considering bankruptcy. He responded, “I don’t waste a lot of time thinking or planning how to fail.” Weatherford’s stock hit 14 cents last week as the company plans to file for bankruptcy.

Things haven’t been going well for shale producers despite higher oil prices, which averaged $65 a barrel in 2018 (for U.S. pricing standard West Textas Intermediate) and was the highest average price since 2014.

Jeff Miller, the CEO of oil services company Halliburton, recently made some dire predictions about shale’s ability to continue record oil production.

“Higher activity and more advanced technology will be needed to maintain flat production levels,” said Miller. Higher activity and more advanced technology mean higher expenses. And that would apparently be required just to keep production at current levels.

Buffett’s Big Bet in Permian Bidding War

Warren Buffett in 2010. Credit: White House, public domain

It is easy to see why Warren Buffett sees this as a time to be “greedy.” Many others are failing with their investments in U.S. shale oil and seem fearful of getting a return on capital in shale oil and gas production.

Despite others’ fears (or perhaps because of them), Buffett decided to back Occidental with $10 billion for its purchase of oil company Anadarko and its prized Permian holdings. This was no bargain.

Initially it looked like oil major Chevron would be successful with its $33 billion bid to buy Anadarko. But then Occidental started (and ended) a bidding war with an offer reportedly totalling $57 billion, made possible in part by Buffett’s $10 billion.

Occidental’s share prices have hit a 10-year low since the deal was finalized and one criticism has been the very favorable terms surrounding Buffett’s investment. This isn’t the first time Buffett has struck a deal like this. During the financial crisis, his company bailed out Goldman Sachs with a $5 billion loan, again with favorable terms for him. Buffett did well on that investment and could stand to profit on this deal as well, thanks to the generous terms.

CHART OF THE DAY: Occidental Petroleum shares plunge to a 10-year low (down more than 6% today) after Chevron walks away from takeover battle for Anadarko, giving Occidental the victory | #OOTT $OXY pic.twitter.com/3YEZPy5NZb

— Javier Blas (@JavierBlas) May 9, 2019

However, Buffett is not a seasoned oil industry expert and apparently agreed to the $10 billion loan after just a 90 minute conversation. That is a lot of money to bet on a simple premise: that the Permian can produce oil profitably. Apparently that 90 minute conversation convinced Buffett it’s possible. He explained his rationale: “It’s also a bet on the fact that the Permian Basin is what it is cracked up to be.”

Perhaps the terms of the deal shield Buffett’s investment from any real risk, but whether Buffett understands the Permian and the finances of fracking better than someone like Scott Sheffield of Pioneer is up for debate.

Despite the U.S. fracking industry’s history of “capital destruction,” one of the top investors in the world has bet big that Occidental holds the secret to Permian profits. But perhaps this time really will be different, or perhaps Occidental will follow in the footsteps of Halcón and others who bet it all on the Permian and lost.

Main Image: 738C9717.jpg by Esteban Monclova under license CC BY–NC 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts