Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is getting a lot of attention these days, with U.S. producers making major investments in the infrastructure to produce and export LNG to China and the rest of the world for the next several decades.

That’s despite LNG looking like a big bet that may not ever pay off.

A common question about the super-chilled, easier-to-ship form of natural gas is whether LNG will become “the next coal.” This is a reference to the U.S. coal market’s failure, in part due to climate concerns, but mainly because it can’t compete economically with other sources of electricity, including renewables.

To counter those coal comparisons, the oil and gas industry is working hard to push LNG as the “fuel of the future” and is getting plenty of help from members of Congress. Last week, the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources held a hearing on “The Important Role of U.S. LNG in Evolving Global Markets,” which was chaired by Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), a big supporter of developing infrastructure to export LNG from Alaska to Asia.

While the committee featured the usual industry supporters from Congress, this hearing showed a healthy amount of skepticism about the future of LNG exports.

Nikos Tsafos, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Energy and National Security Program and a major promoter of LNG, gave a less than confident assessment about that future.

“Whenever you make 25 year bets, some people are bound to be wrong,” Tsafos told the committee.

Similar skepticism was abundant at a presentation held this week by Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy. The presentation reviewed the International Energy Agency’s report “Gas 2019 — Analysis and Forecasts to 2024” by Jean-Baptiste Dubreuil, a senior natural gas analyst at the International Energy Agency (IEA).

The report highlighted the rapid expansion plans for the global LNG industry, with the U.S. leading the way. However, the panel discussion that followed painted a more nuanced picture.

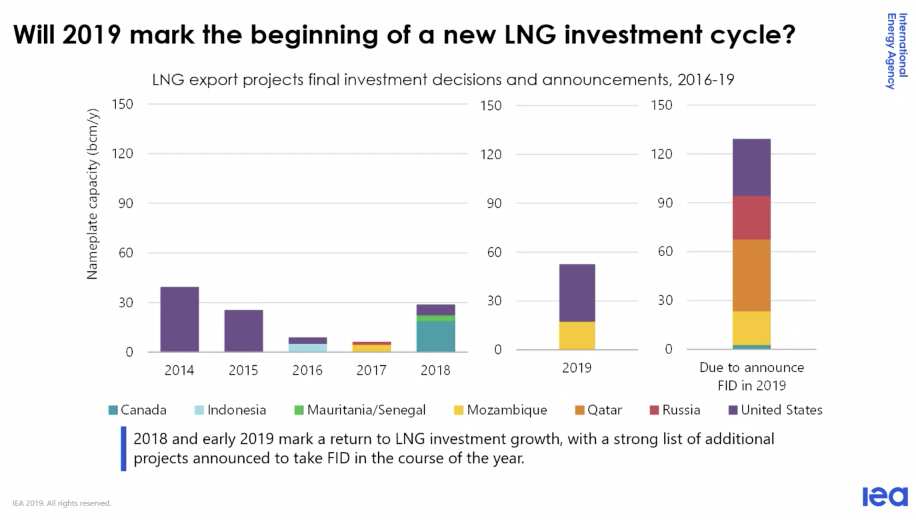

Planned LNG export projects around the world. Credit: International Energy Agency

Panelist Leslie Palti-Guzman, co-founder and president of the oil and gas industry firm Gas Vista, noted one of the main reasons for the expansion was that is was “driven by the race between suppliers.”

“Many exporters are fearing the closing of the window of marketing opportunity or fearing stranded assets,” Palti-Guzman said. “It’s really driven by the sentiment that it is now or it may never happen for many exporters and suppliers.”

Palti-Guzman also highlighted how climate concerns could affect LNG‘s prospects and questioned whether the public will accept the risks of a future based on a fossil fuel. “One key risk to the outlook [of LNG] will be the social acceptance of gas and whether gas is the next coal,” said Palti-Guzman.

Gas producers are trying to lock in future demand for their product now by building export terminals, pipelines, and other infrastructure, or face the possibility of stranded assets, a situation in which their natural gas reserves would be left untapped.

Platts S&P Global also just released the report “New horizons: The forces shaping the future of the LNG market.” It concludes that: “The stakes are high. Global fossil fuel demand is expected to peak over the next decade, threatening trillions of dollars in energy asset investments.”

Another recent study concluded that even using the existing fossil fuel infrastructure already built, including that of natural gas, will push the planet past the international goal of limiting warming 1.5°C (2.7°F) by 2100.

This latest research confirms that plans for LNG expansion are a climate disaster waiting to happen. Nevertheless, the oil and gas industry is desperate to avoid stranded assets and is instead betting on a big future for LNG.

Confusing National Security Arguments for LNG Exports to China

Both the oil and gas industry and its proponents in Congress are looking to secure as much natural gas infrastructure and future demand as possible. However, to make this argument, they are forced to make some considerable leaps of logic.

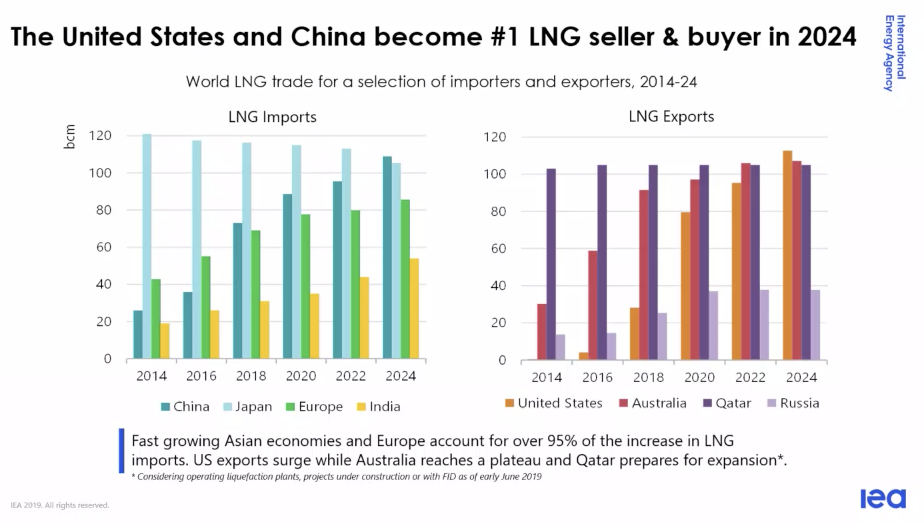

It is highly likely that the U.S. will become the largest exporter of LNG, and China will be its biggest customer. However, that situation leads LNG supporters in Congress to make some contradicting statements.

Predicted LNG exports/imports through 2024. Credit: International Energy Agency

One supporter is Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.). He is pushing the proposed Appalachian Storage Hub project, which would form the backbone of a whole new petrochemical industry in West Virginia, one based on the region’s natural gas supplies. Sen. Manchin is arguing that this project could give the U.S. more leverage over countries like Russia and China.

“Not only would it be an economic driver for the region but it would also increase our national and economic energy security,” Manchin said in a statement July 16. “With countries like Russia and China continuing to leverage their energy resources for political influence, it is more important than ever for the United States to secure energy independence.”

The obvious flaw in this argument is that the petrochemical development proposed for West Virginia would be largely financed with $83 billion from China. Similarly, China is proposing to invest in Alaskan LNG infrastructure.

Not everyone at last week’s Senate hearing thought this trend was a good idea.

Melanie Hart, director of the China Program at the liberal public policy think tank Center for American Progress, was one of the witnesses for the hearing and pointed out the obvious conflicts of interest with China investing in U.S. gas infrastructure.

“If those deals move forward, the Chinese Communist Party will have tremendous leverage over local economies in two great American states,” Hart told the committee.

Hart also brought up another flaw in the current plan to produce natural gas in America and export it as LNG to China. “There is no strong commercial business case for exporting large quantities of U.S. LNG to China,” Hart said. Current market conditions (plus a trade war) mean China can meet its rapidly growing LNG demand with lower cost non-U.S. suppliers like Australia.

In April Jordan McNiven, an analyst with energy-focused investment bank Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co, told the Wall Street Journal that for the Asian markets U.S. exports were “basically out of the money” and that the message from Asian markets to U.S LNG exporters was “don’t send us any more LNG, we’re good.”

Not exactly a great start to a 25 year bet on selling U.S. LNG to China.

We Live in Two Different Worlds

At the end of the Columbia panel’s discussion about LNG this week, an audience member addressed the topic that had been ignored for the whole discussion — how increased investments in natural gas infrastructure are completely at odds with achieving climate goals.

“It seems as though we are living in two different worlds. The Paris climate agreement is to reach zero carbon by 2050 and you’re talking about the increased investment in natural gas, LNG, pipelines.”

The panel had no real answer or explanation in response.

Agreed: “The @IEA continues to be stuck in the past when it comes to championing gas and other fossil fuels…The IEA should focus on improving its energy scenarios to align with the 1.5-degree goal within the Paris Agreement” – @david_turnbull https://t.co/KZWmmWrZjo

— Lila Holzman (@lila_holzman) July 18, 2019

Another disconnect the panel did not address was the IEA‘s prediction that natural gas prices will remain low. Because current prices are at historical lows and many gas producers in the U.S. are losing money at these prices, this trend is an unlikely scenario.

As recently reported by DeSmog, Steve Schlotterbeck, the former CEO of shale gas producer EQT, pointed out that the economics of gas production mean prices will have to go much higher and the only question is whether that happens gradually or quickly. That price shift is a potential risk that S&P Platts also noted in its new report: “The industry is still exposed to abrupt investment cyclicality, a phenomenon known to cause disruptive supply shocks, price volatility, and demand destruction.”

Even when ignoring the issue of climate change, there is no strong economic case for the sheer scale of plans to expand the global LNG industry. Gas producers understand the very real risk of overinvesting in LNG and natural gas, but the alternative — to leave it in the ground — is simply not an option the industry wants to accept, and is instead racing to avoid being the last terminal or pipeline built.

As Leslie Palti-Guzman told the audience at Columbia this week, it is now or never for those wanting to place 25-year bets on LNG. But a lot of evidence points to these being bad bets — just like coal.

Main image: LNG SOKOTO, KRVE 61, SMIT EBRO & SMIT SCHELDE. Credit: Kees Torn, CC BY–SA 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts