While fracking for oil and gas in the U.S. has contributed to record levels of fossil fuel production, a critical part of that story also involves water. An ongoing battle for this precious resource has emerged in dry areas of the U.S. where much of the oil and gas production is occurring. In addition, once the oil and gas industry is finished with the water involved in pumping out fossil fuels, disposing of or treating that toxic wastewater, known as produced water, becomes yet another problem.

These water woes represent a daunting challenge for the U.S. fracking industry, which has been a financial disaster, something even a former shale gas CEO has admitted. And its financial prospects aren’t looking any rosier: The industry is facing another round of bankruptcies as producers are overwhelmed by debt they are unable to repay.

This week, Bloomberg reports that the Permian region of Texas and New Mexico, a fracking hotspot, will need an estimated $9 billion of new investment to create 1,000 new injection disposal wells to deal with fracking wastewater over the next decade, citing a note to clients from financial services company Raymond James and Associates.

Permian needs $9 billion worth of new wells—but not for crude #Water #Wastewater #SDG6 #Permian #Oil #Gas #Fracking #Wells #Texas https://t.co/kte3tjLyMZ via @mwtnews

— Noah J. Sabich (@NoahSabich) July 31, 2019

“Most investors are simply unaware of the fact that as crude production grows, produced ‘dirty’ water grows even faster,” wrote Raymond James analyst Marshall Adkin.

In July the industry analysts at Wood MacKenzie — who have been highlighting issues about water and fracking for some time — pointed to this factor, and its financial impacts, only getting worse, while also predicting wastewater output in the Permian would double in the next four years. “The entire Permian production cost curve is shifting as produced water volumes expand, posing a risk to production growth in the most prolific U.S. shale play,” wrote Wood MacKenzie.

Meanwhile, Wall Street is aware of this fact and is viewing the water crisis in the fracking industry as another way to profit from fracking while investors lose their shirts. Natural Gas Intelligence reported that Raymond James noted this water problem was “offering substantial market opportunities.”

In March, a headline on Reuters also emphasized this point: “Wastewater – private equity’s new black gold in U.S. shale.” So, from the perspective of private equity, the more wastewater, the better.

Oil Industry Buying up Water

During fracked oil and gas production, a mix of freshwater and chemicals are blasted down into the shale or other rock to release oil and gas. Some of that injected water also comes back up, along with produced water from within the rock which can be extremely salty and contains naturally occurring radioactive materials, chemicals, oil residues, and other contaminants.

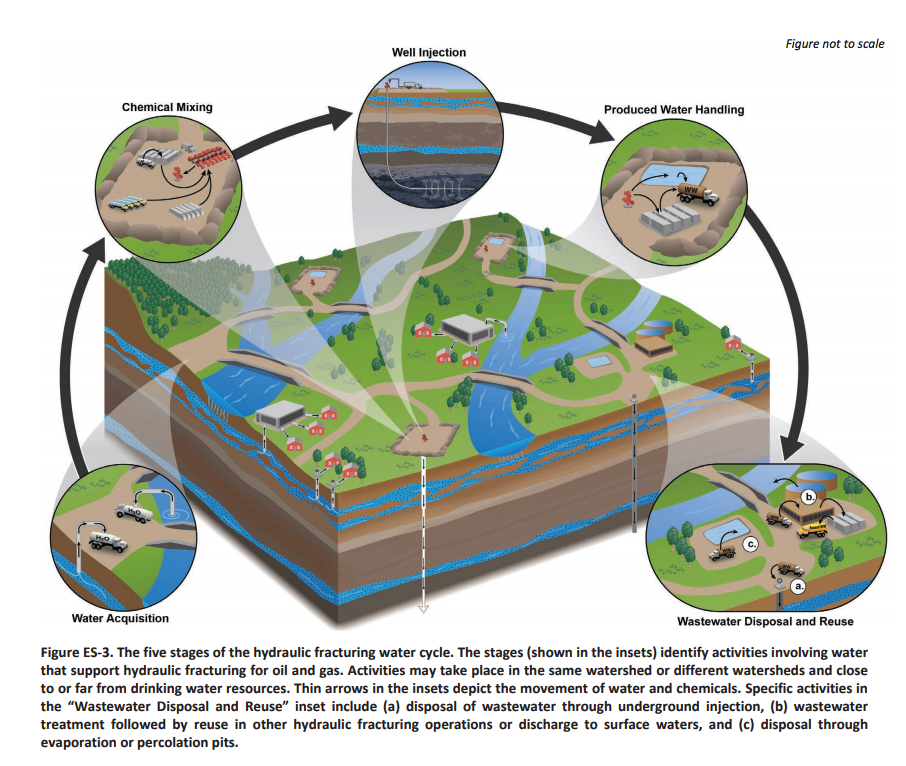

A graphic showing the water cycle during hydraulic fracturing. Credit: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2016

That’s where the wastewater comes from. But the initial water injected into the rock has to come from either groundwater or surface lakes and rivers.

In places like Texas and New Mexico, freshwater can be in short supply. That also presents a huge money-making opportunity for some.

“Water is the new oil,” Laura Capper, a Houston-based oilfield consultant, explained to the publication Finance & Commerce. “The value of water has changed.”

Big money is being spent to lock up the rights to freshwater in Texas, in order to sell those rights to oil and gas producers. Finance & Commerce reported one sale of a family farm for $32.5 million. This farm was sold at a premium to other recent sales. Initially, the sale was supposed to be an auction, but that was canceled when an oil investor’s pre-bid was higher than anyone else was willing to pay. Interestingly, the family first had hoped to get rich off of potential oil and gas reserves on the farm, but instead hit it rich with water.

Of course, the water that goes to the oil industry is no longer available for people to use it for many other uses, such as drinking, electricity, and agriculture. Similar concerns were expressed in a July Wall Street Journal story about another large farm selling off its water in Texas’s Chihuahuan Desert region. A single landowner there has plans to sell up to 25 million gallons of water a day.

“I don’t know why the hell you would want to pipe water out of the desert,” said Kirby Warnock, a farmer from the area. “It’s like space shuttle astronauts selling their oxygen. It boggles my mind.”

The extraction model of the oil and gas industry is now being applied to water. Those who sell the commodity will make their money and have the option to move on. But water is a limited resource in Texas.

Still, laws there allow landowners broad leeway to do what they want with water on their land. Inevitably, the aquifers they are drawing from will become depleted by the oil industry’s thirst for water — making a few people very wealthy — and leaving the rest high and dry.

New Mexico’s New Rule for Fracking Wastewater

New Mexico has a water problem and is hugely dependent on water from the Colorado River. But the viability of that source is potentially at risk as a rising population creates greater demand for water, and the region remains locked in long-term drought.

The state, home to part of the Permian Basin oilfields in eastern New Mexico, currently draws water for the fracking industry from Texas. As one Texas farmer who was selling water to the oil industry recently told the Texas Tribune, “If it wasn’t for Texas water, New Mexico wouldn’t have no oil production.”

The Tribune also reports that New Mexico is accusing Texas farmers of stealing water from New Mexico aquifers to then sell back to New Mexico. As the old saying goes, “Whiskey is for drinking, water is for fighting over.”

With real water shortage issues facing the state, New Mexico recently passed a new law allowing fracking wastewater to be treated and reused by the oil and gas industry. The law was a direct effort of the industry and has environmentalists concerned because it opens the door for recycled fracking wastewater to be used for other applications, including irrigating farmland (which has happened in California) or even being added back to drinking water supplies — something the oil and gas industry is eager to explore.

#NavajoNation, which covers parts of Arizona, Utah, & New Mexico, 1000’s of ppl still struggle to get clean running drinking water, many travel 50+ miles 2 get water .#NativeAmerican https://t.co/0Qgj6BC6ZC

— Becca Ramos (@BeccaFromTX) August 1, 2019

“There’s an opportunity to catch up on produced water and potentially open doors to reuse that water for other purposes, or to save or recycle that water for additional production purposes, and that could be a huge opportunity for oil and gas,” Robert McEntyre, spokesman for the New Mexico Oil and Gas Association, told the New Mexico Political Report.

Some of the problems with reusing fracking wastewater are that not only can it have high levels of salts and chemical contaminants, but it also can be radioactive, drawn up from natural sources in rock. This is a documented problem with fracking wastewater in North Dakota and Pennsylvania.

Even more troubling is that the Trump administration is trying to weaken safeguards related to radioactivity, with some officials even claiming that low doses of radiation make people healthier. In addition, the Trump Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) decided it was “not necessary” to update the federal standards for handling toxic waste from oil and gas wells, including fracking waste, even as unconventional oil and gas wastewater volumes shoot up.

Creating Wastewater Where There Is Little to Waste

In addition to hosting plans for a huge fracking expansion in the Permian region, Texas is home to two of the fastest growing cities in the country. Meanwhile, the fastest growing city in the country is Phoenix, which also holds the title of “least sustainable city” in the country.

Population trends combined with weather trends and the expansion of fracking in the American Southwest all point to a huge looming battle for water.

As in Australia and Texas, so it will be in BC with fracking: “A Texan tragedy: ample oil, no water – #fracking boom sucks away precious water from beneath the ground, leaving cattle dead, farms bone-dry and people thirsty” https://t.co/OUwNEju5Jn #bcpoli #cdnpoli

— Lindsay Brown – Stop Site C dam (@Lidsville) August 14, 2018

“We don’t want it to be pumped dry,” Greg Perrin, who runs the Reeves County Groundwater Conservation District in Texas, told The Tribune, “You don’t want to see it being able to produce a world of water and then just use it for the oilfield industry.”

Main image: Fracking and agriculture compete for land and water near Denver City, Texas. Credit: NASA, CC BY–NC 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts