Most activities I do these days are monitored, thanks to the small army of devices I carry about my person. On any given day, I’ll know how many steps I took, my resting heart rate, how deeply I slept. In theory, this information is meant to make me a better, healthier person.

But there’s something I haven’t yet been able to track: what I breathe. So when I was offered a free trial of a new portable air pollution monitor, I leapt at the chance.

Air pollution is known as the “silent killer”. According to the UN, dirty air is claiming seven million lives a year, with 90 percent of the world’s population at risk.

While it’s a global threat, it is also a local issue, with pollution levels varying street-by-street. Air pollution is caused by a number of factors, including the combustion of fossil fuels and transport, which emit particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, and other pollutants that can end up in the lungs and airways, causing both long- and short-term health issues, particularly for people who already suffer from lung and heart problems, and for vulnerable groups like children and the elderly.

I knew all this, but I didn’t know whether the air I personally breathe was dangerous. I hoped that, by carrying around an air pollution monitor for a day, I could see whether my daily habits were putting my long-term health at risk.

Out on the town

Honestly, I didn’t know what to expect. More than 40 cities across the UK are at or exceed the World Health Organisation’s air pollution limits, including Newcastle-upon-Tyne, where I live. But unlike the years I spent in London, when the haze across the Thames was sometimes visible on hot summer days, I haven’t worried much about what I’ve been breathing – despite the fact that I have to cycle across a motorway to get into the centre of town.

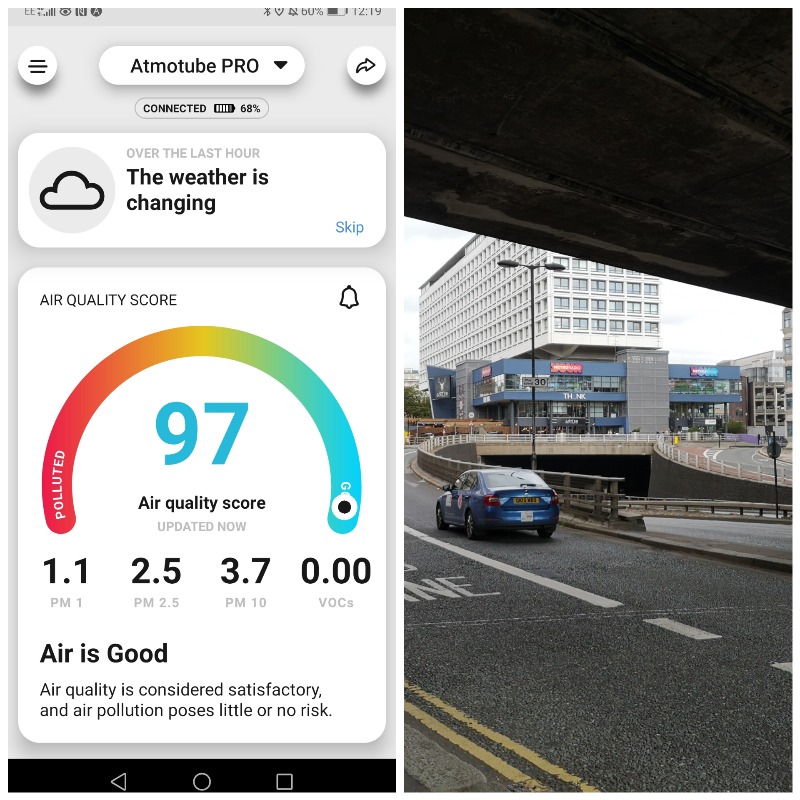

So, on a reasonably sunny September day, I attach my Atmotube Pro to my bag and set off, on foot, into town. The device, a small back box containing a quietly whirring fan, is connected to my phone. This fan collected the air, which is then analysed for particulate matter and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), both of which can be harmful to humans. An app provides me with constant updates on the air quality, including alerts if it drops below a certain level.

The WHO says that, over the course of a year, humans should not be exposed to an average of more than 10 micrograms per cubic metre of the fine particles known as PM2.5, or to more than 20 micrograms per cubic metre of the coarser PM10 particles. Despite this, studies have found that there are no “safe” levels of exposure of PM2.5 exposure, with a 7 percent increase in mortality with each additional 5 micrograms per cubic metre.

Somewhat perversely, I am disappointed when it delivers a positive reading as I step out into my leafy suburb. Does this thing even work? The answer comes at the end of my street, as I walk through a small area of road works, and the digital dial suddenly spins to the left: dust.

Other than that, the air quality score remains high as I walk into the centre of the city, and even as I pass over the motorway.

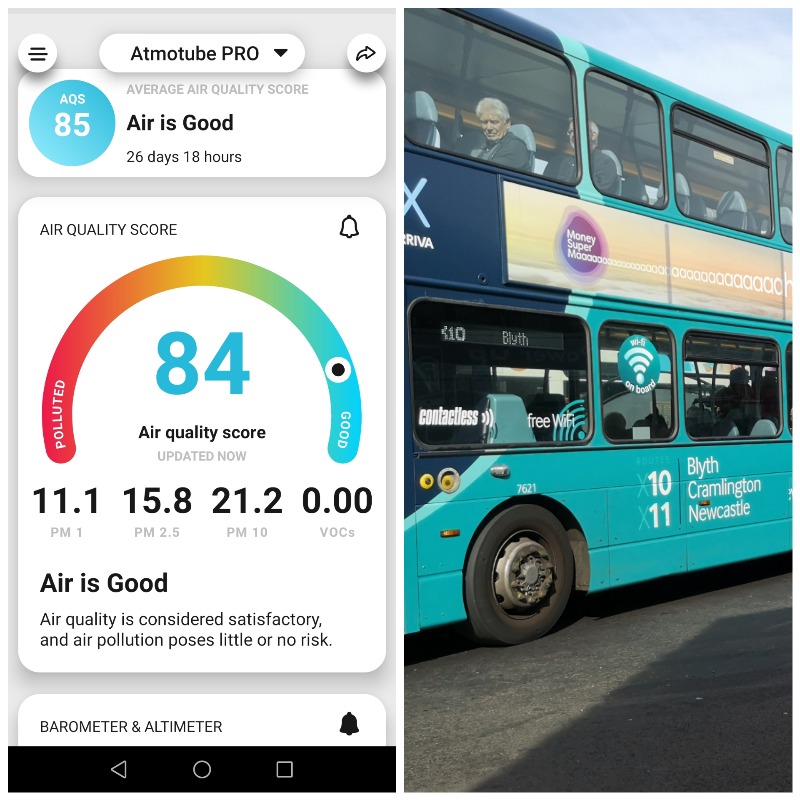

Then, the dial starts to move again. I have reached the bus station, and instantly the air exceeds the WHO’s guidelines. The PM2.5 count ratchets up to 17 micrograms per cubic metre, and the PM10 count up to 22 micrograms per cubic metre.

Of course, I’m unlikely to sit at the bus station for an entire year, so this probably isn’t going to be a problem for me personally. But for people who have to work in this area, the levels are high enough that it could start to pose a health risk.

Other than that, levels of particulate matter throughout the city streets remain fairly low. That’s in line with what Newcastle Council reports. It monitors PM2.5 and PM10 at two locations, and neither site exceeds the WHO’s guidelines.

But these positive readings disguise a problem: the greatest air pollution problem in the city is not PM2.5 or PM10, but nitrogen dioxide (NO2). While Newcastle reports fairly low levels of particulate matter, an investigation by Friends of the Earth found that NO2 levels across the city were well above the WHO’s recommendations.The Atmotube Pro cannot measure this; nor can it detect ozone, another common pollutant.

I ask Atmotube about the lack of an NO2 sensor, and a spokesperson responded: “We aimed to design a consumer-level but still precise portable air quality monitor… More precise electrochemical NO2 sensors have bigger sizes and don’t fit inside a small device like Atmotube.”

Caffeine stop

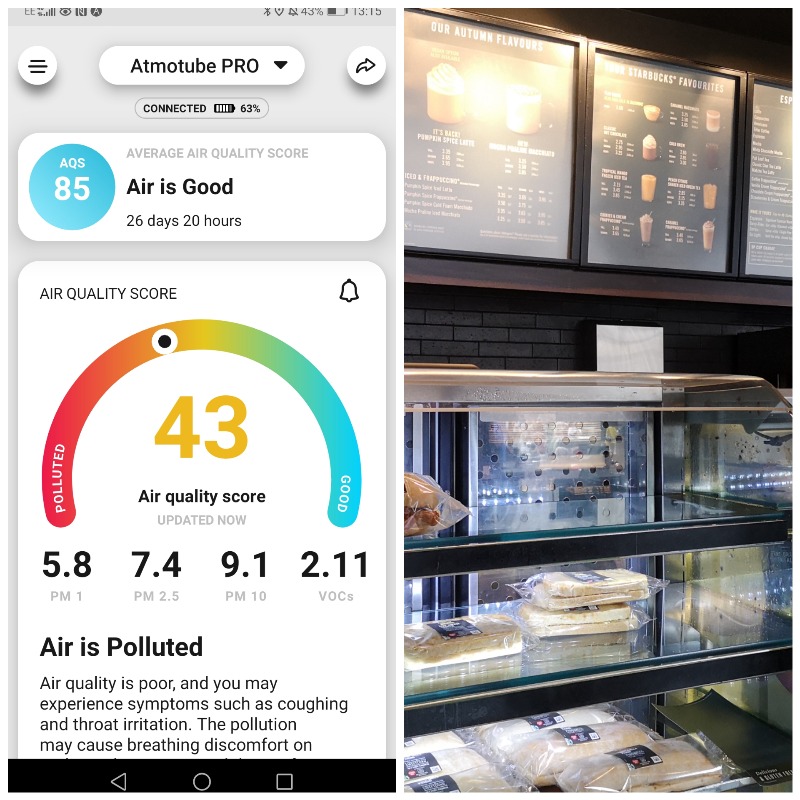

Air quality isn’t just an issue for the streets: indoor air can also be toxic, as I discover when I stop for a coffee. Suddenly, the air quality dial plummets. I’m getting a reading of 53, and my phone warns me that I “may experience symptoms such as coughing and throat irritation”. (I don’t.)

This dramatic drop in air quality is thanks to a sudden hike in VOCs. There’s no official safe levels for these substances, which are numerous and derive from products like paints, varnishes, detergents, cleaning products, photocopiers and printers. Such a figure would be largely irrelevant anyway; a single measure “reveals little regarding the nature of the individual compounds, their concentrations and possible toxicity,” according to a recent paper by scientists from Public Health England.

Nonetheless, with my monitor showing readings of more than 2,000 parts per billion – and with the risks ranging from eye irritation to cancer at just 16 parts per billion for one VOC, formaldehyde, for example – I would at least want to ask some questions if I worked at this coffee shop. And I’d probably think twice about sitting there with my computer for the day; the reading at the cafe where I normally work is reassuringly low.

The verdict

It’s been a long day: I’m reliably informed that I’ve walked 22,000 steps and burned around 1,056 calories in the interests of testing the gizmo. After all this, do I see myself tracking my air quality as systematically as my movement?

It’s certainly been an interesting experiment. I’m more aware now of the variations in the air I breathe. Newcastle’s air, on the whole, proved almost suspiciously clean – I suspect my walk along the motorway wasn’t quite as cleansing as my mobile app suggested. It would have been useful to see data on additional pollutants that have been highlighted by other, more rigorous monitoring efforts.

However, that might have to come at the expense of portability, and a clear advantage to Atmotube is its flexibility. While the Council only monitors four locations, I can track the places that are important to me, in real time: my home, my commute, my favourite cafes. In some circumstances – choosing a school, moving house – this information could lead to an ultimately life-saving decision.

The app creates a map of air quality readings from around the world. And while there are still too few devices out there to create a meaningful dataset right now, I can see this being a valuable source of real-time information in the future.

So while I can’t see my air pollution monitor becoming quite so surgically attached to me as my smartwatch, I can see myself using it when there’s an important decision to be made. And that, in itself, is probably the healthier approach.

Atmotube provided me with the Atmotube Pro for free, but had no editorial input or oversight of the contents of this article.

Title image: Wojtek Gurak. All other images by Sophie Yeo.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts