The head of a federal committee tasked with advising the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on air quality science recently disparaged a new Harvard study examining the link between air pollution and coronavirus fatalities across the country. The EPA adviser’s critical remarks appear consistent with his track record of disregarding robust science on air pollution and health risks in his consulting work for industry clients such as tobacco and fossil fuel interests.

Dr. Louis Anthony (Tony) Cox Jr., who is chair of EPA’s Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee, criticized a preliminary study from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in comments made to the Washington Examiner. Cox — who previously produced his own study on air pollution and health risks that was funded and edited by the American Petroleum Institute — questioned the validity of the Harvard study, which was released publicly in early April but has yet to undergo formal peer review.

The study, which links the type of fine particulate air pollution produced by cars and power plants to higher COVID-19 mortality rates, has been submitted for review and publication to the New England Journal of Medicine.

“It was rushed out without being properly vetted,” Cox said. He called the study a “bogus piece of analysis” and “technically unsound.” According to Cox, the study is “fundamentally flawed” and “has sensational policy implications, none of which are trustworthy.”

That study found that even small increases in fine particulate matter (PM2.5) exposure is associated with a statistically significant increase in the COVID-19 death rate. It is the first study to examine the link between long-term particulate matter exposure and coronavirus risks in the U.S., and the results are consistent with other peer-reviewed studies finding a correlation between COVID fatalities and air pollution in Europe and, most recently, a preliminary analysis in Louisiana’s Cancer Alley.

NEW: Important research from @HarvardChanSPH linking dirty air with coronavirus deaths. It’s the 1st nationwide study & it finds places with even slightly higher PM 2.5 levels will likely have far higher Covid-19 death rates than less polluted areas.https://t.co/yVoWmhQoLA

— Lisa Friedman (@LFFriedman) April 7, 2020

The Harvard study has already garnered attention in Democratic policy circles. A trio of Democratic Representatives cited it in a letter expressing concerns over an EPA policy to relax environmental compliance obligations during the pandemic. Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey’s office also cited it in a recent brief on environmental injustice and coronavirus.

Democractic presidential candidate Joe Biden referenced the study in an online fact sheet about his plan for a “clean energy revolution and environmental justice.” And in April the study authors discussed their findings with members of the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis.

According to H. Christopher Frey, who has studied air pollution for over 30 years and chaired EPA’s Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee from 2012 to 2015, the Harvard study linking fine particulate matter exposure and worsened coronavirus outcomes “is no doubt the first of more to come.” He said the Harvard researchers behind this study previously published epidemiological research showing the harmful effects of human exposure to fine particles, which is part of a robust science indicating deadly impacts of fine particulate (or particle) air pollution.

“What is lost in the media coverage of the recent Harvard study is the strong causal link between human exposure to fine particles — before, during, and after the pandemic — and premature death,” Frey told DeSmog via email. “There is strong evidence, based on multiple peer-reviewed studies that span a wide range of locations, population demographics, housing characteristics, and so on, that exposure to fine particles at levels below the current air quality standards causes premature death and numerous disease outcomes.”

Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, in 2011. Credit: John Phelan, CC BY 3.

But for Cox, who now leads the EPA advisory committee that Frey formerly chaired, the Harvard study’s findings are not convincing. “I would have zero confidence in the published results of this study because its interpretation, design, and analysis are fundamentally flawed,” he told the Washington Examiner.

“The statistical models developed by the Harvard team ignore crucial real-world interactions among risk factors, such as that PM2.5 cannot kill people where there are no people to kill,” Cox explained to DeSmog. He said the models also “omit crucial information and demographic variables” that could help explain reported associations. “For example, the model omits a variable, the ‘rural-urban continuum,’ that could help examine whether the reported association between PM2.5 and COVID-19 mortality risk is explained by the fact that both are higher in more crowded areas,” he said.

Francesca Dominici, Harvard biostatistician and senior author of the COVID study, defended Cox’s critiques to the Washington Examiner, saying the team took into account potential confounding variables such as population density and separately analyzed urban and rural counties, with “very similar” results.

A group of 10 agriculture and biofuels organizations called out Cox’s dismissive comments in a May 8 letter to EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler, a former coal industry lobbyist.

“The Harvard School of Public Health has done work with EPA for years. It is shocking to see the Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee be so dismissive of such a highly respected independent party,” a spokesman for the group said in a press release. The letter also points to Cox’s close association with the American Petroleum Institute, with the letter describing him as “the proverbial ‘fox in charge of the chicken coop.’”

Longtime Industry Consultant

Tony Cox is a statistician focusing on risk analysis and is president of Denver-based consulting firm Cox Associates. He has a long history of consulting work on behalf of corporate clients including in the tobacco, fossil fuel, and chemical industries. His industry ties include work in service of tobacco giant Phillip Morris and trade associations such as the American Chemistry Council, National Mining Association, and the American Petroleum Institute (API).

Cox “has a history of attacking established research on the health risks of air pollution,” according to E&E News, and his approach has been to emphasize scientific uncertainty and to question standard risk assessment. He has published studies, for example, that question the relationship between levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and mortality rates.

One of those studies, published in 2017 in the journal Critical Reviews in Toxicology, was not only sponsored, but also copy-edited, by API, a major oil and gas industry trade group. According to E&E News, “Cox denied that API influenced his work and said the organization did not suggest any substantive changes.” Cox has done other research backed by API into air pollution and health risks, as well as the carcinogenic risks of benzene, a chemical in gasoline.

When asked whether his past industry funding sources could affect his research approach and stance on health risks of air pollution, Cox said the short answer is no. He defended his adherence to what he calls “sound science” that demands a “more exacting” analysis and higher burden of proof compared to the traditional weight-of-evidence approach. “I believe that adhering to principles and methods of sound science, which leave no room for what funding sources believe or want, serves both science and the public interest far better than other approaches, and will continue to apply that approach in reaching conclusions,” Cox told DeSmog.

Studies show that industry-funded research may bias results and tends to produce more favorable results for its backers, in areas from psychology to medicine to sugar and obesity.

Cox acknowledged that his approach has been “met with enormous backlash.” Frey said Cox’s treatment of air pollution risk assessment is “disregarding the law.”

“The Clean Air Act requires that EPA set air quality standards that protect public health with an adequate margin of safety. The standards should be set based not just on known, but also anticipated, adverse effects,” Frey explained. “With Dr. Cox leading the way, the current [Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee] has imposed a burden of proof for evidence of adverse effects far beyond that required by the Clean Air Act.”

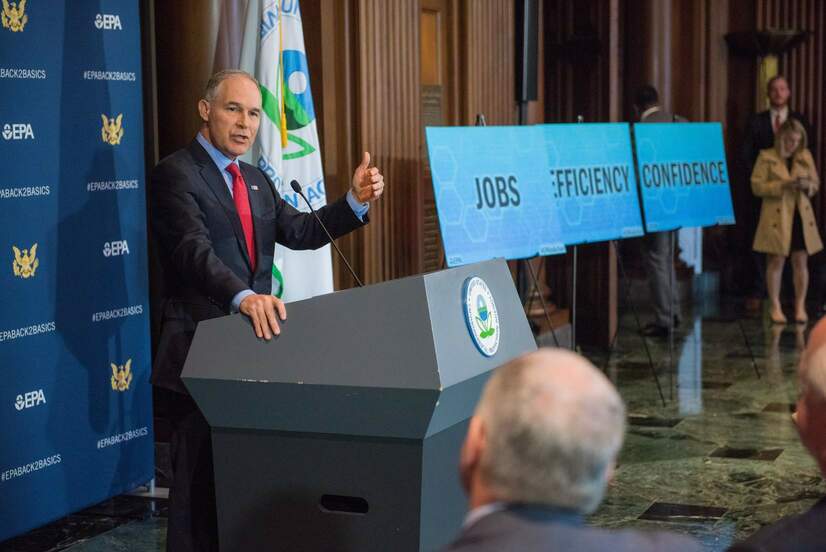

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce nominated Cox to chair EPA’s Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee, and former EPA head Scott Pruitt ushered Cox into that role as part of a move that replaced many of the independent scientists on the agency’s Science Advisory Board with industry-affiliated experts.

Purging Independent Scientists From EPA Advisory Board

As noted in 2017, Cox was one of three nominees to the Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee that raised red flags. The other two were S. Stanley Young, who is affiliated with climate science–denying Heartland Institute, and Deane Waldman, who directs the Koch, Exxon, and tobacco industry-funded Texas Public Policy Foundation’s Public Health Center. Cox became chair of the committee and both he and Young were put onto EPA’s Science Advisory Board.

Senators Tom Carper (D-DE) and Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) raised concerns about these two ultimate appointments in a January 9, 2018 letter to then-EPA Administrator Pruitt. “Specifically, it appears that public commenters warned that Drs. Louis Anthony (Tony) Cox, Jr. (a researcher for the petroleum industry) and S. Stanley Young (a researcher for the pharmaceutical and petroleum industry) may have financial conflicts of interest, may risk an appearance of impartiality, and may lack the scientific expertise necessary to serve on one or more Federal Advisory Committees,” they wrote.

Then-EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt re-opening auto emissions rulemaking in 2018. Credit: EPA, public domain

The senators also expressed concern with Pruitt’s decision to bar scientists who received EPA grant funding from serving on EPA advisory committees and to instead appoint individuals with clear ties to regulated industries.

“We are concerned that some of the newly-appointed members of these nonpartisan scientific advisory committees and boards may have financial and ethical conflicts of interests,” they wrote. “In addition, some of these individuals may not possess the appropriate level of scientific expertise or credentials. This underscores our concern that your actions to replace many highly-qualified members of these committees — including the unprecedented action to remove any scientist who was a recipient of EPA grants from eligibility — has led to Federal Advisory Committees that are not balanced in viewpoints, and to the appointment of committee members who are either not qualified or not impartial. This approach undermines the process of providing sound, science-based advice that EPA can use as a basis for environmental regulations that are aimed at protecting human health and the environment.”

A federal court recently ruled that the EPA cannot prohibit its grant recipients from serving on its advisory panels.

EPA’s Science Advisory Board generally does have some industry-affiliated scientists — they made up 40 percent of the board under President Obama — but under Trump they have come to dominate the agency’s science board, comprising 68 percent of the members.

As Reveal News explained in 2017, “Pruitt transformed the board from a panel of the nation’s top environmental experts to one dominated by industry-funded scientists and state government officials who have fought federal regulations.”

‘Sidelining Science’

In mid-April, just a week after the Harvard study came out, EPA posted a proposed decision to retain the current regulatory standards for fine particle pollution, a decision that ignored evidence showing that strengthening the standards would save lives.

“Leaving the standards alone is a threat to public health, because thousands of premature deaths each year could be prevented by a more stringent science-based standard that meets the legal requirements of the Clean Air Act,” Frey told DeSmog.

Gina McCarthy, president of the Natural Resources Defense Council and former EPA Administrator under the Obama administration, called EPA’s decision to retain the particle pollution (soot) standards “indefensible.”

“EPA’s own scientists say more than 12,000 lives could be saved every year by strengthening the national limits for soot,” she said in a statement.

Today, the Trump @epa dodged an opportunity to save *more than 12,000 lives a year* by failing to issue a more protective federal limit on harmful soot.

That’s indefensible. https://t.co/MsZl2MT7lA

— Gina McCarthy (@GinaNRDC) April 14, 2020

But as Frey explained, Trump’s EPA appears to have little interest in heeding the science.

“EPA political appointees are ignoring, disregarding, and sidelining science in pursuit of their ideological agenda of regulatory rollback,” he said.

“Mr. Wheeler’s proposal to retain the current fine particle standards is a floundering example of red herrings, strawmen, and other logical fallacies,” Frey added. “The danger is that the courts may not be able to sort this out and, even if they do, it will take time during which Americans will continue to suffer under an inadequate standard.”

Main image: The New York National Guard registers people at a COVID-19 Mobile Testing Center in Glenn Island Park, New Rochelle, March 14, 2020. Credit: Sgt. Amouris Coss/The National Guard, CC BY 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts