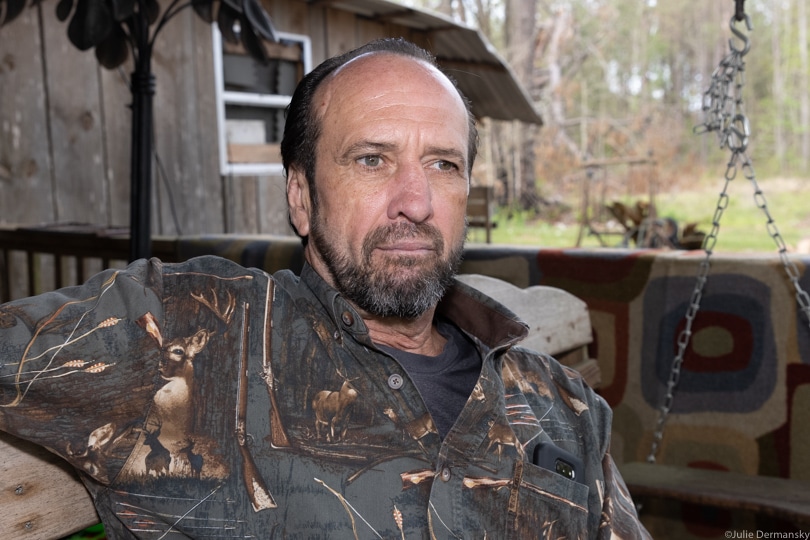

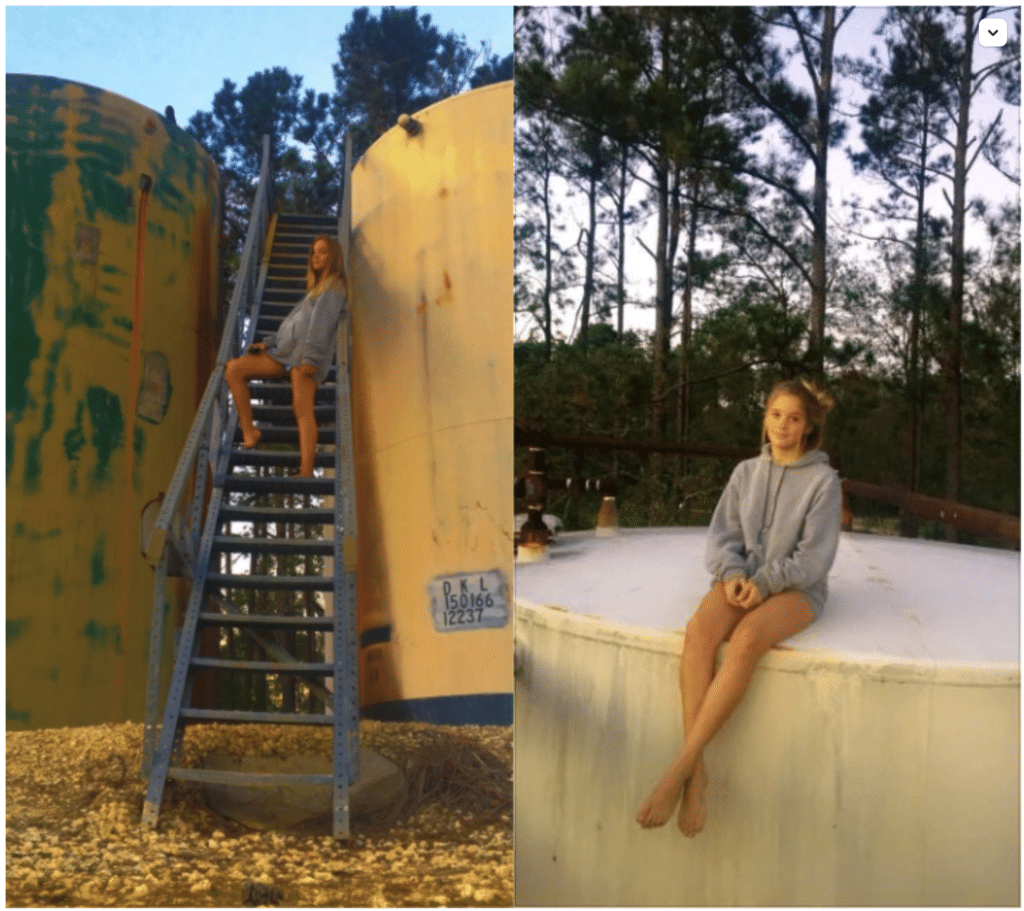

Maxwell Smith is on a mission to make sure no one loses a child the way he lost his 14-year-old daughter, Zalee Gail Day-Smith. Zalee, a vivacious high school freshman who loved singing, died on February 28 when oil tanks exploded near her home in Beauregard, Louisiana. “Her body was thrown 200 feet in the air,” Smith told me when I went to visit the family a month after the accident. Zalee’s body was found across the street from the site of the blast in the Bear Field oil field, just north of Lake Charles. It was located alongside one of the oil tanks that had been blown off its foundation. Smith says that his daughter’s body was mutilated to such a degree that the family was never allowed to see it.

Zalee lived with her mother, sister, and twin brother about a hundred feet from the oil field site owned by Urban Oil and Gas LLC, a Texas-based company that holds numerous oil and gas leases in Louisiana and several western states.

“The landlord told us it was ok to play on the site,” Mattisun Miner, one of Zalee’s older sisters told me. Douglas Kent Carroll, Zalee’s older brother, also said that the landlord made it clear that the tanks next door to the home were nothing to worry about. The landlord did not respond to a request for comment. The rural area is littered with oil field sites that range in activity from actively producing wells to permanently decommissioned ones, and everything in between. So, when Carroll’s family members moved into a house next to one of these sites, it didn’t raise his concern at the time. He now knows better.

After the explosion, Zalee’s father and other family members started looking for answers about her death and are now devoted to finding ways to protect other children from the dangers of oil and gas industry sites in Louisiana. They hope that their efforts can spare other families from suffering the pain of losing a loved one as they have.

At the Urban Oil and Gas site that exploded is an injection well that was used to dispose of wastewater from oil production and a tank battery — a set of storage and processing tanks — in this case, two of which stored oil — that were linked to two shut-in oil wells nearby, according to Patrick Courreges, communications director for the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources (LDNR). In 2012, one of the wells was shut-in, meaning the operator purposely turned a valve to stop the well from producing, a process which can be reversed to later restart production. The other well was shut-in in February last year, not long before Zalee’s family moved in.

Her family was under the impression that this oil field site had been permanently decommissioned. But Urban Oil and Gas had only paused production and left oil in the storage tanks on the property next to Zalee’s home. The site had no apparent activity while the family lived next to it — they were evicted shortly after the explosion — and there was no sign describing its current status.

The Louisiana State Fire Marshal’s Office described the site of the explosion as an inactive oil field. According to a March 4 press release, a multi-agency investigation into the cause of the explosion is ongoing. It also noted that Zalee’s “presence near the tanks moments before the incident has been identified as a contributing factor in the case.” When asked how Zalee’s presence on the site might have contributed to the explosion, Ashley Rodrigue, public affairs director for the fire marshal’s office, would not elaborate.

An early media report from KPLC, a local TV station, included the fire marshal’s statement in a way that implied the explosion was in some way Zalee’s fault, says her brother. The TV station later added a statement to its online story from her family’s lawyer, reiterating that the investigation is ongoing and that ”the family is extremely distressed about investigators releasing incomplete statements that cast blame upon the victim.”

Zalee’s family members said there were no warning signs at the oil industry site and no indication that people were prohibited from being there. There wasn’t even any fencing to stop people accessing the site. “If Zalee had been told the site was dangerous, or that she was trespassing if she went near the tanks, she would never have gone there, but she didn’t know — it was her hangout place,” her sister Miner said. “Lots of kids hung out there including the landlord’s granddaughter.”

Even with the added statement to KPLC’s report, Douglas Kent Carroll, Zalee’s old brother, said the TV report would make you think Zalee was up to no good. The family assured me that she was a straight-A student, didn’t smoke, and didn’t want to cause damage to anything.

Urban Oil and Gas disputes the family’s claim about a lack of signage on the site. “There was indeed signage on the property,” Carolyn Alvey, a spokesperson for Urban Oil and Gas, wrote in an email, saying that it included a “no trespassing” sign, a hazardous material sign, and a notice to “keep off the tanks.” Photos and video which Zalee’s family showed me do not indicate any obvious warning signage was present. The only sign that appeared in the photos I saw was a required sign next to the injection well with the operator’s name and the site’s identification number.

The driveway leading into the site and the roadway on it were often used as a shortcut across the property, according to Zalee’s family members, and not only by them but by local officials too. During hurricane season last year, Miner said local officials told the family it was fine to use the oil field driveway to reach their home, which was no longer accessible without passing through the industry site.

I asked Alvey if the company knew people were using the company’s driveway and did not receive a response before publication.

“If I had known the site was inactive, and not abandoned,” Zalee’s father Smith, a former oil and gas industry worker, said, “I would never have let her play there or let other family members use the driveway.”

He says he didn’t know that the oil wells tied into the tank battery that blew up were classified as “Shut-In/Future Utility,” which means they are no longer productive, but not yet plugged and abandoned. If the wells were plugged properly, the site wouldn’t have been explosive. That information can be found online at the State’s Strategic Online Natural Resources Information System (SONRIS), but isn’t widely known to those who live around well sites. The status of the wells isn’t made clear on signage at the site, according to Smith, and there is no regulation requiring it, which is something he said needs to change.

The State of Louisiana requires oil well operators that discontinue production at a well for good to plug the well by filling it with concrete before it is considered permanently closed and abandoned. However, companies can cut off a well’s production and leave the possibility open for later use by “shutting-in” that well, as Urban Oil and Gas did with its wells connected to the tank battery that blew up. Shut-in wells are simply left in an inactive state, keeping the possibility of reactivating them later.

While oil fields in any state should not be used as a playground, Courreges of LDNR said that an inactive site is undoubtedly more dangerous than an abandoned well site.

There is no requirement for an operator with an inactive site to remove any oil that may be stored in tank batteries at the time the wells stop producing. And because sites can stay inactive for years, oil can remain in tank batteries for years too. If operators who shut-in wells had to remove oil from their tank batteries, the danger of an explosion would be eliminated at such sites like the one that took Zalee’s life.

I asked Urban Oil and Gas how much oil was in the tanks at the time of the explosion but did not receive an answer.

The lack of federal or state safety regulations at active and inactive oil field sites dumbfounded Smith. “Not requiring warning signs and fencing around the site — it is like leaving a bomb unattended,” he said.

“We don’t have regulations telling oil and gas site operators they need a fence or warning sign at volatile sites near homes, but we have laws requiring you wear a helmet when on a motorcycle and you must have a fence around a swimming pool in Louisiana,” Smith said.

“We have warning requirements on everything these days,” Zalee’s brother Carroll pointed out, “but not for oil wells and tank battery sites.” That just doesn’t make any sense to him or the rest of their family.

In his research after the accident, Smith learned that the Louisiana Environmental Action Network (LEAN), an advocacy group based in Baton Rouge, has been pushing to pass legislation that would protect people from the kind of dangers that took his daughter’s life. He says he was devastated to see how over and over again state politicians have voted against this proposal, because he believes if such a law had been passed, Zalee might be alive today.

Smith reached out to Marylee Orr, LEAN’s executive director, last week to seek help with his own efforts. LEAN is part of the Green Army, a coalition representing environmental and social justice organizations led by retired Lt. Gen. Russel Honoré, that spearheaded the effort to pass legislation to protect people from orphaned and abandoned wells in 2014; the legislation, however, did not pass. Since then, LEAN and the Green Army have continued to push LDNR for reform.

Orr feels strongly that people who live near oil and gas sites should be warned about activity and potential dangers at them and says that these sites need to be clearly marked that they are dangerous. “Zalee’s death is heartbreaking,” Orr said, adding that she believes a warning sign at the site might have prevented this loss of life.

Honoré, famous for his response as a U.S. military commander during Hurricane Katrina, was tapped by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi to lead the security investigation into the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol.

“If I hadn’t been in Washington, I would have gone out to meet with Zalee’s family right away,” Honoré said. He told me that he is haunted by Zalee’s death. “A child has died because the state law allows companies like this company from Texas to come here and create a hazardous situation without warning signage or fences to keep children or anybody a safe distance away.”

Honoré plans to continue pressing for better legislation and says he hopes to introduce a bill in Zalee’s name soon.

Wilma Subra, LEAN’s technical advisor, hopes that the loss of Zalee’s life will lead LDNR to require at least warning signs and security fencing at all oil and gas sites, whether they are active, shut-in, abandoned, or orphaned wells.

As a result of the explosion and Zalee’s death, “DNR is looking into changing its regulations,” Courreges told me, but says that changes likely won’t happen until after the investigation into the cause of the explosion is complete. He stressed that people should know to steer clear of all oil and gas production sites. He also acknowledged that regulatory action may be needed to ensure people get that message, but said it is too early to say what changes DNR will make.

Zalee’s family members said they are committed to doing whatever they can to make these oil and gas sites safer in her memory. “Making things better for the environment” is something Zalee would have wanted, her father said. Before our interview ended, Smith lamented, “It probably would cost more to bury my daughter than it would have to put a fence around that location.”

CORRECTION 4/2/21: The original version of this article stated that the author had inquired about the amount of oil remaining in the wells, not the tanks. That has been corrected.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts