This factsheet is part of DeSmog’s Agribusiness Database project. For more information, read our full investigation into the meat industry’s messaging on climate change.

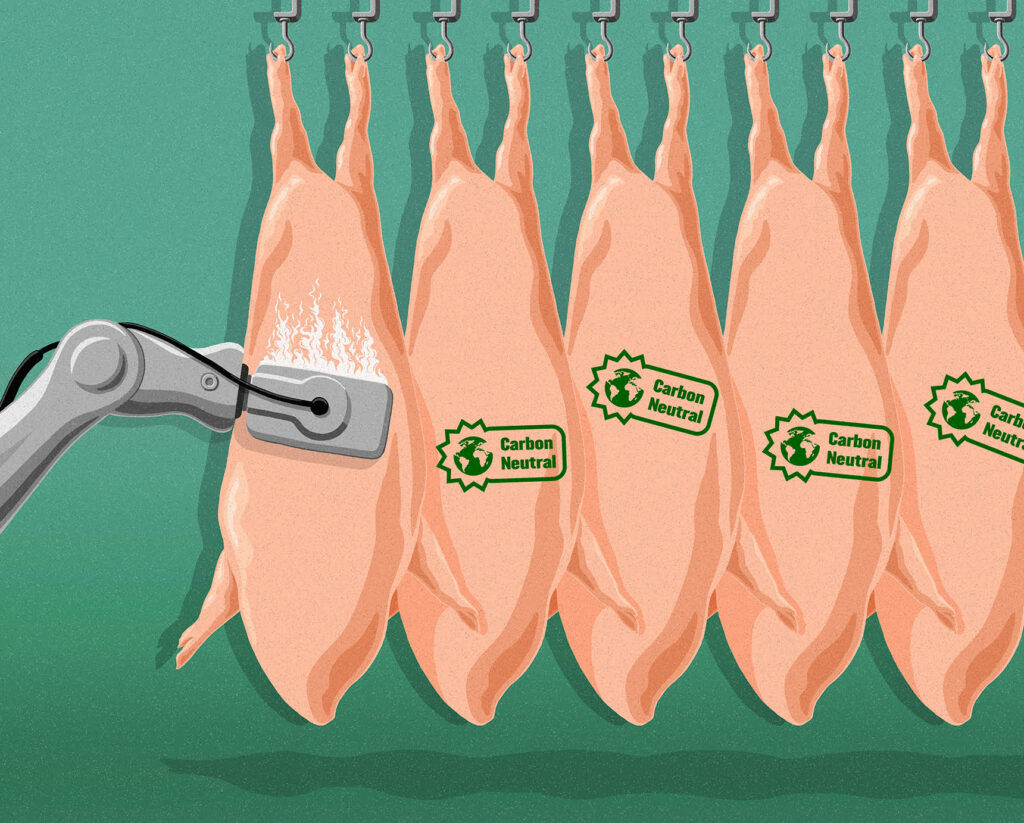

As the climate impact of meat production becomes more publicly known and debated, the meat industry has developed several narratives to portray meat as “part of the solution” and industrial scale farms as potential “heroes” in this discussion.

According to environmental experts and campaigners, the meat industry downplays the climate impact of animal agriculture and exaggerates the potential of different innovations to reduce it, depicting meat as indispensable to feeding the world’s population while denying the need to cut consumption globally to reach climate targets.

The profiles in DeSmog’s Agribusiness Database provide a summary of the ways in which the meat industry measures its climate impact and promotes meat production as climate-friendly. Here is a summary of the main criticisms of the meat industry’s claims.

Meat companies downplay their climate impacts by excluding the majority of their emissions

According to a 2021 study by researchers from the New York University (NYU) Department of Environmental Studies, meat companies “emphasize mitigating energy use, with limited focus on emissions (e.g., methane) from animal and land management and land-use change, which make the biggest warming contributions in the agricultural sector.”

Many companies do not consider “scope 3” emissions in their emissions reporting (including Danish Crown, JBS, Vion Food Group and Tyson Foods), which account for the majority of their greenhouse gas (GHG) footprint. Scope 1 and 2 emissions stem from direct activities of an organisation or activities under their control and the production of energy used by the organisation. Scope 3 emissions are all other indirect emissions from activities of an organisation, which include, in the case of animal agriculture, emissions produced by farms supplying meat companies and land use and land-use change related to grazing and animal feed production.

For example, while Brazilian meat giant JBS reported emissions of 7.14 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (Mt CO2e) in 2019, organizations such as GRAIN, which advocates for small-scale farming, and the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (IATP), a US-based sustainable farming research organisation, estimate that JBS has the “largest climate footprint of any meat company in the world, with independent calculations suggesting that in 2016 its emissions rivalled Taiwan’s at 280 million tonnes of CO2-eq.”

The NYU study also found meat industry groups, such as the International Meat Secretariat, were involved in shaping the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) methodology for measuring livestock emissions, likely allowing “for some influence over how [the sector’s] emissions are accounted for, and subsequently how their environmental impact is understood by the public.”

According to environmental researcher Nicholas Carter, the FAO’s livestock emissions reports were conducted by livestock specialists “with an inherent bias to improve this sector internally,” undercounting methane emissions and excluding key data points such as emissions caused by livestock respiration and aquaculture, as well as the “opportunity costs” associated with using large amounts of land for livestock production. A review conducted by Carter estimated that livestock is responsible for at least 37 percent of GHG emissions.

Sustainable farming campaigners such as the U.K. charity Feedback have criticised the focus of meat producers’ emissions strategies on scope 1 and 2 emissions, stating in 2020: “They’re farming companies using the emissions reduction strategies of transport companies rather than coming up with strategies that are consummate with the fact that they are meat and dairy companies.”

‘Animal agriculture isn’t a serious driver of climate change’

Meat industry leaders are increasingly marketing meat as sustainable, arguing that meat production in countries such as the U.S. and U.K. only accounts for a small proportion of national emissions while locally produced meat reduces transport emissions. Producers claim their animal feed comes from responsible sources and their livestock use land unsuitable for other uses, all the while supporting biodiversity and capturing carbon from the atmosphere through holistic or other types of “regenerative” grazing.

According to a 2021 NYU study, however, the US meat industry “takes advantage of large overall US emissions and frames emissions as a relative percentage rather than absolute terms” to downplay the industry’s climate footprint, at the same time as excluding certain scope 3 emissions sources.

The report quotes data from a previous study indicating that US beef production is responsible for 3.7 percent of total US emissions at approximately 243 teragram CO2e, noting that “despite this relatively small percentage, these emissions represent nearly 40 percent of the emissions of the US agriculture sector, which has a sizeable footprint globally at ~661 Tg CO2e (EPA).”

A 2019 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report concluded that the emissions caused by the global food system will increase by 30 to 40 percent by 2050, without intervention such as dietary change towards more plant-based diets.

According to an analysis published by Oxford University’s Our World in Data project, the transport, processing, retail, and packaging of food, account for only a small share of emissions, while most GHG emissions caused by animal agriculture result from the production of the meat itself. These come from deforestation, changes in soil carbon, methane emissions, emissions from fertilisers, manure, farm machinery, and animal feed production.

Many meat companies report plans to ensure that soy within their supply chain is verified as responsibly sourced by programs such as the Round Table on Responsible Soy (RTRS). But a 2021 report by Greenpeace described RTRS’s claims of supporting responsible feed production as “misleading, allowing companies a green image even if they are still contributing to human rights abuses and/or the destruction of nature.” It noted that “the vast majority of RTRS soya sales are based on credits” and that credit buyers “thus might not know whether the producers of the actual products they are buying are engaging in deforestation or other ecosystem destruction.”

Concerning the meat industry’s argument that some pastures cannot be used for other forms of agriculture, University of Oxford researcher Marco Springmann argues that “if everybody were to make the argument that ‘our pastures are the best and should be used for grazing’, then there would be no way to limit global warming.” According to a 2010 study on managing soils to mitigate climate change, soils used for agriculture contain 25 to 75 percent less soil organic carbon “than their counterparts in undisturbed or natural ecosystems.”

A 2018 metastudy conducted by researchers from Oxford’s Food Climate Research Network concluded that “better management of grass-fed livestock, while worthwhile in and of itself, does not offer a significant solution to climate change” and that carbon sequestration achieved through grazing “is small, time-limited, reversible and substantially outweighed by the greenhouse gas emissions these grazing animals generate.”

A 2020 study by biodiversity experts from Aarhus University on how “rewilding” can serve as a climate mitigation strategy identified plant-based diets as a key element to free up land for nature restoration. According to a 2016 study by public health, nutrition and environmental experts, replacing beef with beans in the American diet would free up 42 percent of U.S. cropland and help the U.S. achieve 46-74 percent of the reductions needed to meet the country’s 2020 climate target.

According to a 2021 UN-backed report by Chatham House, meat production is a key driver of global biodiversity loss because animal farming necessitates converting natural ecosystems into agricultural land. A 2020 study by researchers from the University of Alberta warned that scaling up livestock grazing to meet future food demand could threaten the biodiversity of herbivores and pollinators worldwide.

‘Plant-based diets do not solve the problem of climate change’

The meat industry often dismisses dietary change as a means of tackling climate change and claims that meat production only has a small emissions footprint, quoting a 2017 study by researchers at Virginia Tech’s Department of Animal and Poultry Science and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service. Environmental, nutrition and epidemiology researchers have criticised the study for failing to include land use for feed crops in its methodology, as well as “uncritical use of nutritional values and optimization algorithms, and a highly unrealistic and narrow scenario design.”

A 2019 IPCC report concluded that “a dietary shift away from meat can reduce GHG emissions, reduce cropland and pasture requirements, enhance biodiversity protection, and reduce mitigation costs.”

A 2018 study published in Nature found that reducing meat consumption is crucial to lowering the food system’s emissions and that “[i]f socioeconomic changes towards [meat-heavy] Western consumption patterns continue, the environmental pressures of the food system are likely to intensify, and humanity might soon approach the planetary boundaries for global freshwater use, change in land use, and ocean acidification.”

A systematic review based on multiple studies concluded that emissions “differ considerably per diet, with a vegan diet having the lowest CO2eq production per 2000 kcal consumed.” A study published in Nutrition Journal found that a diet modelled on India’s dietary guidelines, such that only plant-based foods are included in the protein group, emits only 0.86 kg of CO2e per day, while the non-vegetarian diet recommended by US dietary guidelines emits 3.83 kg CO2e per day.

An analysis of 85 countries found that most national dietary guidelines were incompatible with climate change targets and that limiting the consumption of animal-based foods had the greatest potential for improving the guideline’s climate impact. A separate analysis from Oxford University’s Our World in Data project found that transitioning to a global vegan diet could save 6.6 gigatonnes (Gt) of CO2e and sequester 8.1 Gt CO2e yearly, resulting in yearly savings of 12.3 Gt CO2e – “almost as much as global food emissions today.”

A study published in Science found that “even if fossil fuel emissions were immediately halted, current trends in global food systems would prevent the achievement of the 1.5°C target and, by the end of the century, threaten the achievement of the 2°C target.”

The meat industry claims that meat causes fewer emissions from food waste than vegetables and fruits since meat is wasted less often, but studies have found “plant-based diets are also more climate friendly when they are wasted.” Researchers from the University of Michigan showed that “fruits and vegetables which comprise 33 percent of food waste [in the U.S.], account for only 8 percent of carbon dioxide emissions,” while animal products “account for 33 percent of food waste by mass and 74 percent of carbon dioxide emissions.” A 2021 study by researchers from Freiburg University and Vienna University of Economics and Business concluded that “an exclusive focus on food waste would potentially mislead policymakers and prevent them from addressing diets, despite [dietary change towards more plant-based diets] being the more effective strategy for reducing resource use.”

‘Meat is needed for a healthy diet and to feed the world despite climate change’

The meat industry frequently portrays meat as a crucial ingredient to feeding the world’s growing population, emphasising the nutritional properties of meat and arguing that diet is a personal choice.

According to a 2019 IPCC report, “consumption of healthy and sustainable diets [including diets low in animal-sourced foods] presents major opportunities for reducing GHG emissions from food systems and improving health outcomes.”

According to the World Resources Institute (WRI), a sustainable development thinktank, feeding 10 billion people by 2050 without transitioning to a more plant-based global diet would necessitate the destruction of the world’s remaining forests and “agriculture alone would produce almost twice the emissions allowable from all human activities.” Meat and dairy products only provide 18 percent of global calories yet take up 83 percent of agricultural land and generate 60 percent of agriculture’s GHG emissions, according to a study published in Science.

In contrast to meat industry claims that the world isn’t getting enough protein, the WRI argues that overconsumption of protein is already occurring in all of the world’s regions, particularly in wealthy countries. The latest protein supply figures from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) for 2013 recorded average protein consumption of 69.1g per capita per day in Africa, 77.57g in Asia, 86.09g in South America, and 102.06g in Europe.

Nutrition experts do say people who follow an exclusively plant-based diet need to take B12 supplements to avoid health risks, a vitamin the meat industry argues is “only found naturally in animal-based products.” But the livestock sector feeds an estimated 90 percent of the global B12 supplement supply to livestock because pesticides and antibiotics used on farms kill the bacteria that produce the vitamin.

Nutrition associations, including the British Nutrition Foundation, approve of meat-free diets, if approached carefully. According to the American Dietetic Association, “appropriately planned vegetarian diets, including total vegetarian or vegan diets, are healthful, nutritionally adequate, and may provide health benefits in the prevention and treatment of certain diseases.”

‘Innovations in animal agriculture will tackle climate change’

The meat industry suggests it will reduce emissions by increasing the sector’s efficiency through innovations such as biogas digesters, precision feed management, more sustainable packaging, improved animal nutrition, and new grazing methods that lead to carbon sequestration.

Sustainability non-profits GRAIN and IATP warn that arguments for emissions intensity reduction “in the absence of targets to reduce the livestock sector’s total emissions” are “dangerous”. They argue that the “large gains in ‘efficiency’ realised by industrial farming in the twentieth century will be hard to repeat without major ecological, social and health impacts.” The organisations describes the efficiency of intensive livestock production as “a myth that is dependent on feeding human-edible cereals to animals who convert them very inefficiently into meat and milk,” noting that “for every 100 calories fed to animals as cereals, just 17–30 calories enter the human food chain as meat.”

Precision agriculture has also been promoted by the agrichemical industry as a solution to climate change, despite questions about the efficacy of the techniques.

Environmental scientists from the University of Oxford have criticised the idea of using cattle grazing to capture carbon, finding that this offsets only 20-60 percent of annual average emissions from the grazing ruminant sector and concluding that “grass-fed cattle remain net contributors to warming.” A study on the concept of “grazed ecosystems,” also known as “holistic management,” further found that “the application of HM [holistic management] principles of trampling and intensive foraging are as detrimental to plants, soils, water storage, and plant productivity as are conventional grazing systems.”

Environmental campaigners have criticised manure management technologies such as biogas digesters for “supporting and helping to perpetuate large-scale factory farming—and in some cases, causing farms to grow in size—under the guise of mitigating climate change.” Others have pointed out that gas produced on factory farms does not qualify as clean energy because burning the gas releases carbon dioxide and other contaminants, while methane-capture technologies fail to address the majority of industrial livestock farming emissions.

One of the meat industry’s suggestions to lower livestock emissions includes adding seaweed to cattle feed. But researchers at NYU’s Department of Environmental Studies and Concordia University regard the benefits of this technique as limited “both in its capacity to reduce cows’ methane emissions and its potential to scale up to the size of the problem” — referring to the size and environmental impact of the livestock sector.