The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is hosting a three-day listening session this week in Louisiana’s capital city to hear the public’s opinions on the state’s bid to take over permitting authority of carbon capture and sequestration (CCS), the fossil fuel industry’s preferred response to climate change.

While the EPA has already expressed its intent to give permitting authority to the state, those who testified on the first day of the three-day public hearing spoke to a deeper matter: Whether the state of Louisiana should continue to tie itself to fossil fuels.

“I support the oil and gas industry because it’s the basic root of Louisiana’s economy and for the industry of all America,” testified Danny Wallace, of Winnsboro, Louisiana. “If the oil and gas industry were to leave this state it would be devastating not only to this state, but all of America. Jobs and careers would be gone.”

“A prior speaker said he worried about his friends who were leaving Louisiana because there were no jobs available. I am concerned about the cacophony, the litany, the long list of friends who have left the state of Louisiana because there is no future here,” testified Jane Patton, who works for the Center for International Environmental Law and lives in New Orleans. “And injecting the oil and gas industry’s waste product under the ground in experimental, proven-to-be-ineffective carbon injection wells is not the climate solution that the people of Louisiana are demanding.”

Federal regulators have not approved any carbon capture and sequestration projects in Louisiana yet. But oil and gas companies are eager to add the technology to their plans to expand in the state as well as retrofit existing facilities with the technology, which would allow the firms to continue burning fossil fuels. Carbon capture and sequestration involves chemically stripping carbon from the exhaust of power plants, fertilizer manufacturing facilities, and other industrial emitters and transporting the gas through pipelines to underground caverns for storage.

Plans for at least 20 carbon capture and sequestration projects in the state have been announced, according to a report commissioned by the 2030 Fund. Half have applied for federal permits.

Recently passed federal subsidies and, potentially, a quicker permitting process are driving fossil fuel firms to develop these plans. Companies successfully pushed for increased subsidies for CCS to be written into the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law that they’re now eager to capitalize on. The industry wants Louisiana to take over permitting of the projects under the assumption that the state would permit projects much faster than the federal government has.

The EPA granted North Dakota permitting authority of carbon capture projects in the state in 2018. Since then, North Dakota has approved a project within eight months, said Marc Ehrhardt, with Grow Louisiana Coalition, an oil and gas industry advocacy group. In comparison, federal permitting takes three to six years, he said. “Louisiana’s energy industry has been the backbone of our state’s economy for a century and has been an essential resource for America’s and the world’s energy supply,” Ehrhardt said. “It’s critical for Louisiana to maintain our place as an energy innovator.”

But other speakers noted that the industry’s success in the state has come at the expense of polluted air for some Louisiana residents. For more than 30 years, the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice has helped Louisiana communities push back against industrial polluters that put their health at risk, said Dr. Beverly Wright, the Center’s Executive Director. “After these steps forward, we are now confronted with the possibility of a major setback,” she said. “Oil and gas companies are now attempting to push us back and lock us into the continued burning of dirty energy dressed up with carbon capture and storage.”

A 2019 Stanford University analysis found that carbon capture technology reduced the climate warming emissions of a coal-burning power plant by a mere 10 percent, while increasing overall air pollution.

The Inflation Reduction Act passed in August 2022, with provisions requested by fossil fuel firms aimed at making the technology economically viable. Carbon capture and sequestration is a costly endeavor in part because of the amount of energy required to run the equipment, which is often fed by burning more fossil fuels. Denbury Inc, Air Products, CF Industries, and Shell — all of which have planned projects in Louisiana — were among the 170 signatories on an August 2021 letter to Congress demanding more subsidies for carbon capture projects be included in what would become the Inflation Reduction Act.

Their requests, most of which made it into the IRA, include increasing the 45Q tax credit values for carbon capture and storage and enhanced oil recovery, extending the timeframe for projects to build, and lowering the amount of carbon that projects need to store to qualify for the tax credits. The IRA subsidies add to those created under the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which included $2.5 billion for CCS demonstration projects, $1 billion for large-scale pilot projects, and nearly $5 billion for CO2 transport and storage infrastructure, according to the Global CCS Institute, which called the law “the single largest CCS infrastructure investment ever.”

The increased subsidies have made carbon capture economically viable for a wider range of polluting facilities including oil refineries and chemical manufacturers, according to the Clean Air Task Force, an environmental lobbying group that has embraced carbon capture technology. But the chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has warned that carbon capture technology alone is not enough to reach climate goals in lieu of reductions in fossil fuel dependence. With so much money at stake, industry players and their proponents made up about half of the testimony on Wednesday in Baton Rouge.

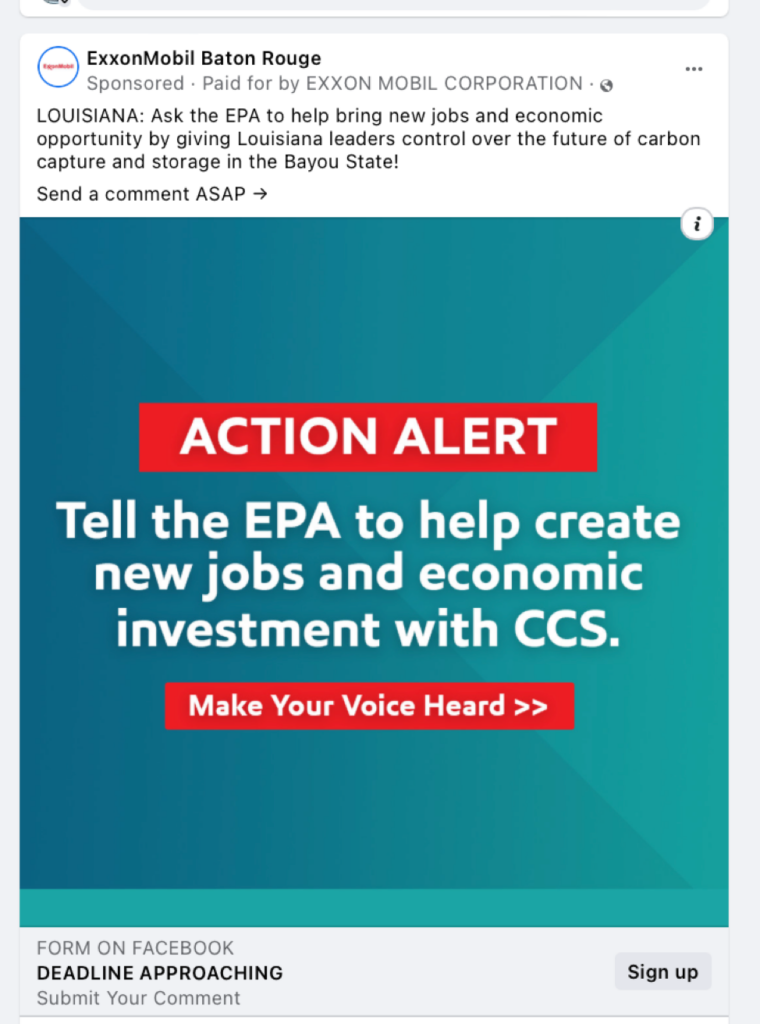

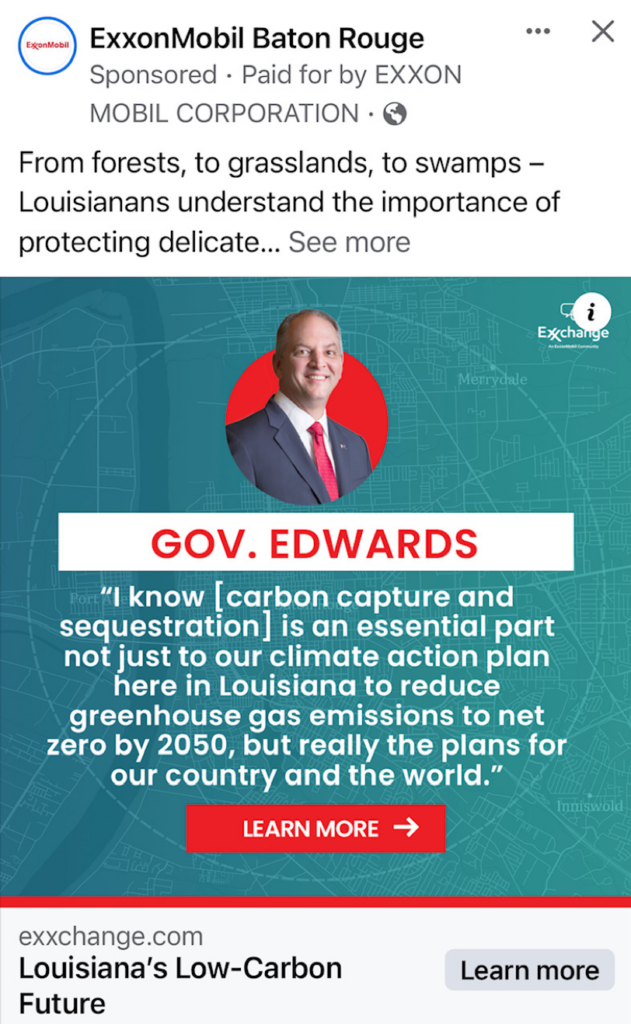

ExxonMobil, which has announced plans to build a carbon storage project in Vermilion Parish in south Louisiana, ran advertisements on Facebook ahead of this week’s hearings. “Tell the EPA to help create new jobs and economic investment with CCS,” one ad reads. Another features a quote from Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards, a Democrat, in support of carbon capture and sequestration.

Still, many residents voiced concerns about the potential public health impacts of carbon capture projects and the thousands of miles of pipelines necessary to feed them. In 2020, a carbon dioxide pipeline in Mississippi, operated by Denbury, ruptured and sent 49 people to the hospital. The same company, which paid the second-largest fine ever levied by the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA), has plans to expand its carbon dioxide pipeline network in Louisiana.

“I’m here to deliver a message to those who would turn Louisiana into a dumping ground. You are not welcome and your efforts here will not be worth your while,” said Jesse George, a policy director for the Alliance for Affordable Energy and a lifelong resident of south Louisiana. “There is a groundswell of people in Louisiana who are willing to challenge every page of permit and oppose every foot of pipeline to prevent further degradation by the same petrochemical companies that have turned our state into an ever eroding cesspool.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts