This article is part of a cross-border investigative series supported by Journalismfund Europe

The coastal city of Freeport, Texas is a dense tangle of metal pipes, tanks and towers. Located 60 miles south of Houston, it’s home to a sprawling petrochemical complex – one of the largest and most polluting in the United States.

Among its facilities is a plant dedicated to the production of ammonia, a colourless compound of nitrogen and hydrogen, and a key ingredient in fertilisers widely used on industrial arable farms – including on fields of barley, wheat and maize across Europe.

Chemicals giants Yara and BASF opened the “world-scale” factory to great fanfare in 2018, promising “cost-efficient” and “sustainable” ammonia production. Unlike conventional plants, which use hydrogen made from natural gas, Yara Freeport would employ a hydrogen “by-product” from neighbouring petrochemicals plants, helping to tackle the fertilizer industry’s sizeable carbon footprint.

But a nine-month investigation by DeSmog and Data Desk, published with The Guardian, reveals that despite these green promises, the facility is relying on hydrogen made from U.S. shale gas — one of the most environmentally and socially damaging fossil fuels – to manufacture its ammonia in Texas.

This investigation was co-published with The Guardian.

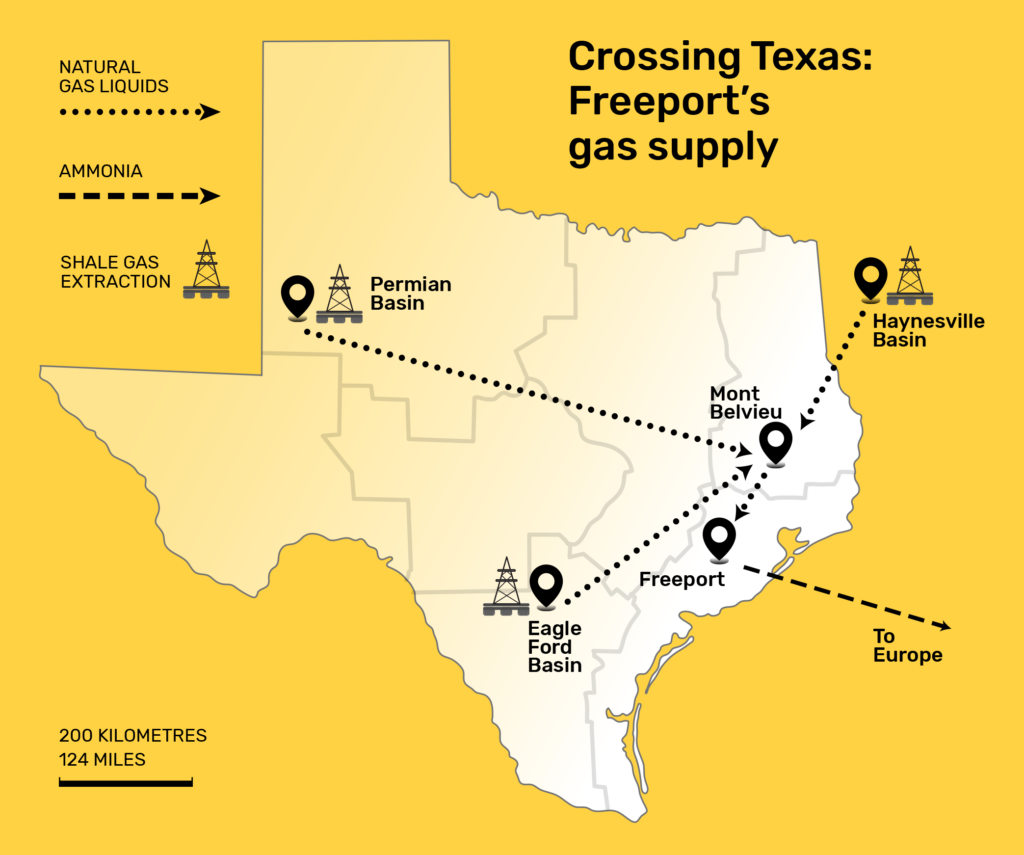

Analysis of pipeline and permit documents traces the source of this gas hundreds of miles west of Freeport to the second largest gas-producing region in the U.S., the Permian Basin, which is widely regarded as a “carbon bomb”.

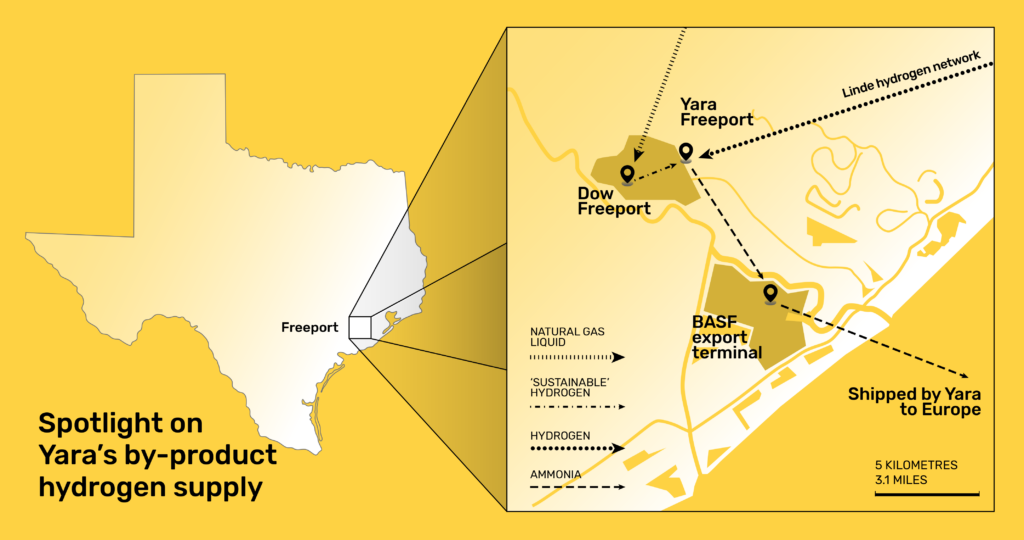

The investigation follows the complex energy supply chain of a Freeport plastics plant through a network of pipelines and storage facilities, revealing fracked gas as the source behind this so-called “sustainable” ammonia. This ethylene plant, operated by U.S. chemicals company Dow, supplies most of Yara’s by-product hydrogen.

Responding to the investigation’s findings, experts said claims by Yara and BASF that the facility produces ammonia without the use of natural gas were “not true at all”. While the recycling of hydrogen at Dow’s plant results in energy savings overall, the fuel has to be replaced with natural gas to heat Dow’s industrial furnace. In this way, they said, Yara Freeport indirectly drives demand for additional fossil fuel extraction.

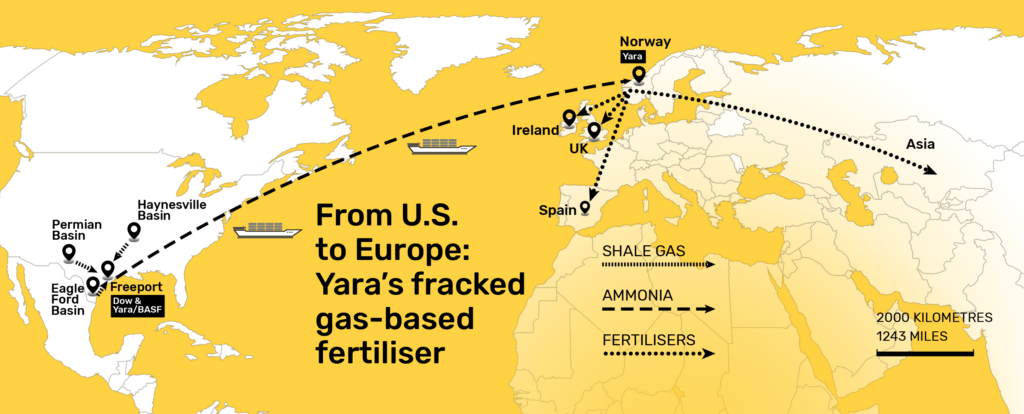

Despite these links to fracked gas and uncertain carbon-savings, the investigation shows that this ammonia is being shipped to fertiliser factories in Europe, including to Yara’s flagship green Herøya plant in Porsgrunn, southern Norway.

Yara – which remains Europe’s largest industrial buyer of natural gas and is globally responsible for emissions equivalent to 16 coal fired power plants each year – claims it is “committed to reducing emissions” and “mitigating climate change”.

Yet shale gas extraction through hydraulic fracturing – known as fracking – releases large volumes of the potent greenhouse gas methane and multiple toxic chemicals and pollutants into the air and water. Studies have found that individuals working and living in close proximity to the Permian Basin and other extraction sites in the U.S. face increased risks of health issues, ranging from asthma and other respiratory issues to preterm birth and cancer.

Responding to DeSmog’s findings, Bernhard Stormyr, Yara’s vice president for sustainability governance, said Yara was “a leader in the transition to lower-carbon fertilizers and low-emission ammonia” and prioritised “profitable decarbonization”. The company acknowledged that ammonia produced at Yara’s Freeport plant “has always relied on hydrogen derived from natural gas”, but said it was “one of the lowest emitters of pollutants and one of the lowest carbon intensity plants in the U.S”.

The company had nearly halved its greenhouse gas emissions since 2005, Stormyr said, and had a target to reduce them by a further 30 percent by 2030 from 2019 levels. However, DeSmog found that the targets did not cover operations at the Freeport plant, or emissions from gas production, according to Yara’s 2024 annual report.

At Yara’s annual general meeting today (28 May), shareholders called on Yara to set emissions reductions targets covering its purchase of fossil-based raw materials. Speaking on behalf of investors worth $1.8 trillion (£1.3 trillion), campaign group ShareAction urged Yara “move away faster from the use of fossil fuels and lead the way in promoting more efficient use of nitrogen fertilisers in global agriculture”.

Yara did not respond to DeSmog’s request for comment regarding the shareholders’ demands. Yara also did not respond to DeSmog’s specific questions about its hydrogen deriving from fracked gas, or comment on the harms or emissions associated with the fuel.

Gas demand for ammonia is expected to boom in the coming decades. The ammonia market will likely triple by 2050, driven by a booming fertiliser trade currently estimated at around $200 billion (£148 billion). The use and production of fertiliser is already a major contributor to climate breakdown – creating more emissions than aviation and shipping combined.

Planned ammonia facilities are also set to quadruple production in the U.S., with 95 percent of this expansion dependent on natural gas. Meanwhile, efforts to tackle fertiliser emissions in Europe appear to have stalled since an ambitious reductions pledge was agreed in 2021.

“European countries and companies claim to be feeding the world with ‘clean’ fertilisers and fueling the future with ‘clean’ energy,” says Taylor Hodge, an agrochemicals campaigner from the Washington D.C.-based environmental non-profit Centre of International Environmental Law (CIEL). “In reality, they’re offshoring the pollution, costs, and risks to communities in the U.S. Gulf South.”

Speaking to DeSmog opposite Yara’s plant, Freeport resident and campaigner Manning Rollerson says he has seen plumes of orange, yellow and green smoke hanging above the BASF facility, which produces a different product from each of its 26 plants.

“Only thing I can say living here, raising my children here — this place takes more than it gives,” Rollerson says. “Every person in this community sits in church praying that God heals them from the cancer that they’re going through.”

Recycling Gas

Yara’s plant in Freeport is the company’s first investment on U.S. soil. The Norwegian chemicals giant – Europe’s largest fertilizer producer – said in its launch press release with German multinational BASF that its use of hydrogen by-product would reduce the environmental impact of 750,000 tonnes of ammonia production a year.

According to BASF – which has a 32 percent share in the plant – Yara Freeport sources its hydrogen inputs by effectively recycling gases produced in nearby plants. The main supplier is the Dow chemical corporation, which produces ethylene for plastics a few hundred metres away from the ammonia plant.

DeSmog and Data Desk reviewed dozens of pipeline maps and permit documents and traced the hydrogen supplying Yara’s plant back to fracked gas stored at Mont Belvieu, a vast salt dome containing dozens of caverns filled with natural gas liquids (NGLs) from several U.S. shale gas basins, including the Permian Basin, Eagle Ford, and Haynesville.

From Mont Belvieu, the fracked gas molecules are piped 90 miles south to Dow, one of the world’s largest ethylene plants – where an intensive steam cracking process produces ethylene and a hydrogen by-product.

Yara told DeSmog that its use of by-product hydrogen, which avoids the conventional process of using natural gas-based steam methane reformation (SMR), reduces carbon emission intensity by 20 percent. But experts told DeSmog that such savings did not go far enough in tackling the sector’s dependence on fossil fuels or its carbon impacts overall.

“Just because it’s a by-product doesn’t mean it’s clean,” notes Paul Martin, a chemical engineer with Spitfire Research, a Toronto-based consultancy specializing in industry decarbonization.

There are other ways in which Yara Freeport’s recycling process is not as green as it claims. While Yara states it’s using a more “sustainable” by-product, Dow’s plant has to use more fracked gas to fuel its furnace to replace the lost heat energy it would otherwise have generated from burning its hydrogen in-house.

The exact quantity of “sustainable hydrogen” from Dow is unknown, but if it met the plant’s total demand, this would amount to around 1.1 million kilograms of natural gas a year, or 1,100 tonnes a day of extra gas, being fed to Dow’s cracker furnaces, according to Martin. He therefore says that while the use of by-product hydrogen is more efficient overall, reducing the amount of fossil fuels required to produce Yara’s ammonia, it’s “not true at all” to say the ammonia production avoids the use of natural gas, since it is also driving up Dow’s use of the fuel.

This gas is then piped from Dow’s factory to the ammonia plant by industrial company Linde, which runs a Gulf Coast hydrogen grid, and provides a back-up hydrogen supply for the companies. Linde itself produces hydrogen at over a dozen facilities along the coast, using gas from shale and offshore extraction, according to analysis of pipeline maps.

Yara and BASF declined to comment on the proportion of hydrogen supply met by Dow versus Linde’s own supply. Dow and Linde did not respond to DeSmog’s questions or requests for comment.

BASF said it was unable to comment on any of its specific operations. A spokesperson said the company was “firmly dedicated to the responsible management of materials at all our manufacturing sites and protecting the environment through efficiency in its production and manufacturing processes, including the joint ammonia production facility with Yara at our site in Freeport, Texas”.

Stormyr, of Yara, defended the terminology used by BASF and Yara in the 2018 press release. “The usage of terms like ‘sustainable,’ ‘green,’ and ‘environmentally friendly’ have evolved considerably,” he told DeSmog. The companies do not appear to have issued a fresh press release on the facility since 2018, or updated the wording used.

Yara’s use of fracked gas makes a mockery of Yara’s “green” expansion in Europe and undermines its attempts at “sustainable” U.S. production, according to Hodge from CIEL.

“The Freeport facility is making ammonia out of hydrogen derived from fossil gas — plain and simple,” she says. “The flow of feedstocks from plastic production and other petrochemical operations makes it clear how deeply these dirty industries are intertwined. Yara’s claims mislead the public about their climate- and community-harming emissions.”

The findings have also raised concerns among experts who have spent years tracking methane emissions in the Permian oil and gas fields, among them Justin Mikulka, communications director at the Texas-based NGO Oilfield Witness.

“We know the Permian is one of the worst hotspots for oil and gas methane emissions globally,” says Mikulka.

“The hydrogen Yara claims to be sustainable starts with methane gas that is extracted from the Texas gas fields. Until Yara switches to using green hydrogen made from water using renewable power, it isn’t possible for them to produce green ammonia in Texas.”

Made with renewable energy, “green” ammonia is the lowest carbon option for making chemical fertiliser, and has been widely promoted by the industry as a way to decarbonise its operations. But the process is costly, and highly energy and water intensive, meaning that only a small handful of projects are operational, accounting for less than one percent of global ammonia production. Yara currently runs a pilot project in Porsgrunn, Norway, where full conversion of the plant was last year put on hold.

In recent years, Yara has invested heavily in “blue” ammonia plants, and is exploring plans for two major new facilities on the Gulf Coast. The fuel is produced through a controversial and largely untested technique, where emissions from ammonia produced with natural gas are captured and stored underground. This will do little to halt the growth of fossil fuels: 95 percent of planned ammonia expansion in the U.S. is expected to rely on natural gas, the vast majority likely to come from fracked gas.

Speaking on behalf of Yara, Stormyr, said the company was “advancing solutions such as hydrogen produced using electrolysis of water and renewable energy instead of natural gas, and carbon capture and storage (CCS), while maintaining full transparency and compliance in how we communicate our product claims”.

Raj Patel, a research professor at the University of Texas at Austin and panel expert at the think tank, the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food), told DeSmog that neither technology addressed underlying issues around fertiliser use and could not provide adequate climate solutions.

“Green and blue hydrogen fertilizers simply prop up an inherently wasteful agricultural model. They don’t touch the root problem – the over-use, pollution and potent greenhouse gas emissions happening on farms,” he said. “We’re applying 21st century technology to preserve 20th century farming problems.”

Destination Europe

Yara recently closed one of its major European production plants in France, and announced its intention to close another, in Belgium. Despite this, the company said that “a strong European fertiliser industry is crucial not only for ensuring food security in Europe and globally but also for enabling Europe to lead the green transition” and has highlighted recent investment plans in green ammonia at plants in Norway and the Netherlands.

Yara made headlines with the launch of Herøya, its first European pilot plant for “low-carbon footprint” fertilizer production in Porsgrunn in 2024, which was described by chief executive Svein Tore Holsether at the time as “a major milestone” for Yara and for the “decarbonization of the food value chain”.

Yara has communicated little about how its European facilities are using ammonia imported from its U.S. plant, stating in its launch press release that it would market its share of ammonia “to industrial customers and the agricultural sector in North America”.

Analysis of customs data reveals that around a quarter of Yara Freeport ammonia is exported outside of the U.S., with over 90 percent of this shipped to Europe to be made into fertilisers in 2023 and 2024. Yara, which does not provide detailed information on commercial transactions between its factories, declined to comment on these numbers.

The vast majority of ammonia was shipped to Porsgrunn and Glomfjord in Norway, the investigation found. In 2024, Yara imported over 100,000 tonnes of ammonia from Freeport to Porsgrunn, roughly one-fifth of its ammonia production capacity.

Less than four percent of the fertiliser produced at Porsgrunn is sourced from renewable electricity, according to DeSmog’s analysis of Yara figures. In October, four months after it celebrated the inauguration of its green hydrogen plant in Porsgrunn, Yara announced it was shelving plans to scale up green hydrogen at both this facility and its plant in the Dutch village of Sluiskil.

In response to DeSmog’s questions, Yara’s Stormyr said that scaling up green hydrogen production at the site was “not possible” until it was economically feasible. “We are closely monitoring developments related to the energy and grid situation, support mechanisms, as well as market and technology developments,” he said.

Yara declined to comment on the volumes of fertilizers produced with renewable electricity at Porsgrunn but said that “only the ammonia based fertilizer produced with hydrogen from electrolysis is sold as lower carbon fertilizer”.

DeSmog and Data Desk were also able to trace 43 percent of Yara’s production of NPK (Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Potassium) fertilisers from shale basins in Texas to Yara’s Norwegian plants in Porsgrunn and Glomfjord.

Fertilisers made at the Norwegian facilities include YaraMila, a type of NPK fertiliser, and YaraLiva. These granular fertilisers – used for everything from wheat and potatoes to fruit – are shipped onwards to Asia and Europe, as well as being sold on the domestic market. Finished fertilisers are also returned to the U.S., as well as to Latin American countries, in particular Brazil, with both countries receiving around 10 percent of exports in 2023.

In 2023, Ireland received around 14 percent of all its fertiliser imports from the facilities, while the UK received around eight percent and Spain almost six percent, according to DeSmog’s calculations.

The global boom in ammonia comes as policies to tackle pollution and emissions from fertiliser production appear to have stalled in the EU. In October 2021, the European Parliament agreed a target to reduce fertiliser use by at least 20 percent across the bloc. But since then, the ambition appears to have been quietly dropped, with no measures taken to translate it into law.

‘Sacrifice Zone’

The chemical giants involved in Yara Freeport’s supply chain have a long history of industrial pollution in the area.

Yara and BASF facilities have both breached air pollution regulation in Freeport in recent years, according to official records from state and federal regulators, contributing to poor air quality for the city’s 11,000 residents.

BASF’s Freeport site faced formal enforcement actions for “high priority violations” of the Clean Air Act, according to 2021 EPA data. Yara’s ammonia plant also failed to comply with air pollution limits between 2018 and 2021, according to Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) records seen by Desmog.

Water pollution is also a major health risk for Freeport residents. The port sits at the mouth of the heavily polluted Brazos River, which flows into the Gulf of Mexico. Dow Freeport was identified as the worst wastewater polluter among plastic plants in the U.S., according to a November 2024 report by the Environmental Integrity Project. BASF factories also exceeded permitted thresholds for water effluent discharge between 2021 and 2025, according to the TCEQ records.

Freeport residents say their city has become a “sacrifice zone”, where historically segregated Black communities have been displaced by industry, and cancer rates caused by air pollution exceed the government’s “acceptable” risk limit. Those living close to industrial plants in Freeport – a city with a majority Latino or Black population – are 22 times more likely to get cancer than the “acceptable” metric, according to a 2021 investigation by media outlet ProPublica.

“They keep bringing all these facilities into small communities because they don’t think we can push back,” says Melanie Oldham, who set up Better Brazoria – a local group that campaigns against air and water pollution – in 2008, after her twins were diagnosed with severe asthma.

Yara and BASF declined to comment on specific questions regarding compliance with environmental regulation in Freeport.

Unfortunately for Gulf coast communities, Yara’s business model hinges on increasing ammonia imports from the U.S. in the near future. In its latest annual report, Yara notes that “our potential investment in large-scale, low-carbon ammonia production in the U.S. aligns well with our European nitrate and NPK production,” adding that the buildout would “enable Yara to capitalize on the anticipated significant growth of the ammonia market by 2050”.

This emerging industry, says Matt Rota, senior policy director at non-profit Healthy Gulf, will hit Gulf Coast communities living near industrial facilities that are already overburdened by pollution.

“Freeport toxic releases to air are one of the worst in the country,” says Rota, “and the Yara plant contributes to that.”

Raj Patel of IPES-Food says the investigation “exposes the bitter truth” of the fertiliser industry.

“While fertiliser giant Yara markets ‘green solutions’, it’s actually pioneering new frontiers for fracking and fossil fuels,” he said. “Our food system is becoming Big Oil’s emergency escape hatch.”

Additional research and reporting by Sara Sneath and Louis Goddard

Editing by Phoebe Cooke

UPDATE (29/05/25): The article was amended to reflect that Yara has announced the intention of closing one of its plants in Belgium, but that this has not yet already closed.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts