This work was supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism

With international treaty negotiations aimed at addressing the plastic pollution crisis resuming in Switzerland this week, a new document reveals that one of the world’s largest plastic producers, DuPont, acknowledged as early as 1974 that recycling its plastic products was not possible.

This new discovery also comes against the backdrop of two pending lawsuits alleging that U.S. plastic producers have deceived the public about the feasibility of recycling since the 1980s.

For decades, the plastics industry has publicly advocated recycling as a strategy for managing plastic waste. But the document, a letter written in May 1974 by Charles Brelsford McCoy, a president and board chairman of DuPont, represents the earliest evidence to date of a top-level industry insider admitting that many commonly used plastic products cannot be recycled due to their complex chemical structures.

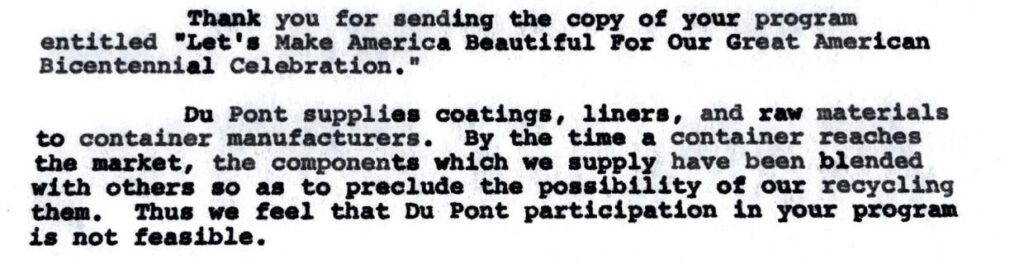

The letter contains DuPont’s response to an invitation asking the company to join a pilot recycling scheme in honor of the U.S.’s 1976 bicentennial celebrations. DuPont refused. The reason: recycling DuPont’s plastic products was simply “not feasible.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts

Found by DeSmog, the correspondence proves that by the early 1970s the plastic industry’s knowledge regarding the limitations of recycling existed at the highest level, not only in the lab but also the C-suite.

The discovery also casts new light on the plastic industry’s decades-long promotion of recycling as a viable solution to the global plastic waste crisis.

Upcoming Plastic Pollution Treaty

On December 1, 2024, the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution held what was supposed to be the final negotiating session for a global treaty against plastic pollution in Busan, South Korea. But a coalition of fossil fuel–producing countries, led by Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Russia, blocked progress, arguing for solutions based on recycling and waste management.

Now, an additional negotiating session will take place in Geneva, Switzerland, from August 5 to 14.

Despite these fossil-fuel producing nations offering recycling as a solution, the process is neither technically nor economically viable for many types of plastic. To date, research shows that only a small fraction — under 10 percent — of all the plastic ever produced has actually been recycled and only 1 percent has been recycled twice.

Some are calling next week’s Geneva session a “last chance” meeting as plastic pollution is considered a major threat to human and planetary health. Made predominantly from fossil fuels, plastic harms the Earth’s climate, biodiversity, and ocean ecosystems, and is also toxic to human health. Plastic microparticles and chemicals have been found all over the globe, from the Mariana Trench to Mount Everest, as well as in human bodies, from the brain to breast milk.

“These industries are intimately linked,” Patrick Boyle, a senior attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), told DeSmog.“Plastics are oil and gas. The fundamental building blocks of plastics as are sourced from oil, gas and coal. They are petrochemicals . . . and fossil fuels are at their core.”

U.S. and European petrochemical companies, represented by the International Council of Chemical Associations (ICCA), joined the push to exclude legally binding restrictions on plastic production from the treaty’s final text, also advocating for recycling as a solution to the crisis and lobbying against legally enforceable limits.

DuPont, BP, Chevron, Dow, ExxonMobil, Phillips, Shell, and TotalEnergies, which collectively make billions of dollars a year from selling and processing the fossil fuel by-products used to manufacture new plastics, are members of multiple lobby groups that pushed against restrictions on plastics production. These lobby groups include the American Chemistry Council and the European Chemistry Industry Council, which in turn form ICCA along with 65 other chemical industry associations from around the world.

“There is a better way to end pollution” said ICCA’s secretary, Chris Jahn, in the aftermath of the talks’ collapse last December. Jahn, who is also the president and CEO of the American Chemistry Council, issued a statement on behalf of the industry-backed Global Partners for Plastics Circularity, renouncing the imposition of restrictions on plastic supplies and advocating for more ambitious national “recycling” plans instead of legally binding limits on production.

Despite internal industry awareness of the technical and economic obstacles facing recycling at scale, Big Oil and the plastics industry have deceptively promoted recycling as a solution to plastic pollution for nearly four decades to avoid legal limits on production or outright bans, according to recent reports by CIEL, NPR/PBS Frontline and the Center for Climate Integrity (CCI).

Davis Allen, lead author of CCI’s report, The Fraud of Plastic Recycling, published in February 2024, told DeSmog that the newly found DuPont letter is “further proof that the plastics industry has been actively deceiving the public for decades about the recyclability of plastics” despite its knowledge of the inherent limitations of recycling.

“The document is striking,” said Allen, “because of its straightforward assessment of the unique challenge of recycling plastics, and because of how little has actually changed over the last 50 years.”

CIEL’s Boyle agrees. “It’s affirming” but also “maddening” to see someone “that high in the company say something that we’ve been saying for years – that plastic recycling doesn’t work,” he told DeSmog.

‘Not Feasible’: A Look Inside the Letter

In April 1974, Charles Brelsford McCoy, then chairman of DuPont’s powerful Finance Committee, received a letter from the Great America Foundation proposing that DuPont take part in a fledgling recycling event as part of the foundation‘s upcoming “Let’s Make America Beautiful for our Great American Bicentennial” celebrations, DeSmog found.

“Our program is not designed to clean up the roadsides of public areas,” wrote the Great America Foundation’s vice president. “It is designed to prevent beverage and other food containers from getting there in the first place.”

Although the iron, steel, and aluminum industries were taking part, McCoy declined the invitation.

“Du Pont supplies coatings, liners, and raw materials to container manufacturers,” he explained. “By the time a container reaches the market, the components which we supply have been blended with others so as to preclude the possibility of our recycling them. Thus we feel that Du Pont participation in your program is not feasible.”

The correspondence, contained within the DuPont archives at the Hagley Library in Wilmington, Delaware, once the site of the company’s 19th century gunpowder mills, adds to previous evidence revealing the plastic industry’s early knowledge that the blending of synthetic polymers and additives involved in plastic production meant that recycling was virtually impossible.

Fossil fuels are used to produce 98 percent of the world’s plastics, each variety with its own chemical composition that prevents different types of plastics from being recycled together. Possible markets exist only for a small number of recycled plastics such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles. The cost of sorting and separating plastics, the addition of chemical additives and colorants, and contamination during the recycling process further limits recyclability. Plastic also degrades with the recycling process, leaching toxic substances that make it unsuitable for many reuses, such as food packaging.

“Best case you’re talking about is one or two cycles of recycling before that original plastic cannot be recycled again into a viable product,” said Boyle. “That’s not recycling in a long-term way, that’s not a circular economy. That’s a cul-de-sac on the way to waste.”

When asked to comment on McCoy’s letter, DuPont spokesperson Dan Turner confirmed that McCoy was an executive with E.I. Dupont de Nemours & Company. He said,“there is a clear difference between DuPont de Nemours and legacy E.I. du Pont de Nemours, and as such, we cannot comment on what was purportedly said by Mr. McCoy in his capacity with E.I. DuPont de Nemours over 50 years ago.”

Turner did not specify what the differences are between the legacy and modern DuPont firms. However, after merging with Dow in 2015, DuPont relinquished control over the companies’ combined plastics division to Dow when the businesses split in 2019. Then, in 2022, DuPont sold its engineering plastics business. It still owns plastics producers, like Donatelle Plastics Inc., a medical device maker that DuPont acquired in 2024.

Historically, DuPont has been one of the world’s largest plastics producers and a 2023 Market Analysis Report described the company as one of “the leading companies in the plastic market” based on data gathered between 2018 and 2023.

Plastic Has ‘Disposal’ Problems

In 1969, at the first U.S. National Conference on Packaging Wastes, a representative from the Dow Chemical Company declared it “ironic” that the molecular structure that made plastic lightweight, durable and popular also created its “disposal problems.” Other participants told the conference, attended by representatives from DuPont, Mobil, Chevron, and Amoco (now BP), that “[t]he very success of package makers in marrying dissimilar materials has made packaging materials virtually unrecoverable after use.”

Because of these challenges inherent within the recycling process, making new plastic from freshly extracted crude oil, natural gas, or coal is much cheaper than paying for recycled plastic.

“The best case you’re talking about is one or two cycles of recycling before that original plastic cannot be recycled again into a viable product … that’s not a circular economy. That’s a cul-de-sac on the way to waste.”

Patrick Boyle, senior attorney, Center for International Environmental Law

When DuPont and other plastics producers eventually shifted to promoting plastic recycling in the 1980s, “it wasn’t because of some technical breakthrough that got around the problem” Allen explains. “It had just become increasingly clear that certain plastic products were likely to get banned if the plastics industry couldn’t make recycling seem like a viable solution.”

A ban on plastics would seriously limit the profit margins of fossil fuel companies and the plastic producers.

Responding to a growing public backlash against plastic waste and facing punitive legislation, the U.S. plastics industry began aggressively promoting recycling as a solution, even though it was unproven at scale. According to CCI’s report, the largest producers, including DuPont, ExxonMobil, and Dow, spent millions of dollars on public relations efforts selling the “myth of plastic recycling” despite their knowledge of its practical limitations.

In 1988, Wayne Pearson, long-time marketing director for DuPont and executive director of the Plastics Recycling Foundation (an industry group whose members included DuPont and ExxonChemical), told the New York Times, “No doubt about it, legislation is the single most important reason why we are looking at recycling.”

That same year, as part of a campaign to make consumers believe in the effectiveness of plastic recycling, the industry introduced a labelling system, grouping plastics by resin type and stamping them with a number surrounded by a triangle of “chasing arrows.” It did this despite internal warnings that these efforts would be “of limited practicality,” according to The Fraud of Plastic Recycling report.

“Recycling cannot go on indefinitely, and does not solve the solid waste problem,” Roy Gottesman, the founder of the plastics industry group Vinyl Institute, acknowledged in 1989.

New Lawsuits Against Major Plastic-makers

Evidence of the plastic industry’s deception over recycling has prompted two recent lawsuits against plastic producers. In September 2024, the state of California filed a lawsuit against ExxonMobil for the company’s alleged “decades-long campaign of fraud and deception about the recyclability of plastics”; and in December 2024, a Missouri-based class action lawsuit, filed against DuPont, ExxonMobil, Chevron, Dow Chemical, and the American Chemistry Council, is seeking an injunction prohibiting these companies from advertising their products as recyclable, court filings state.

“Fossil fuel and petrochemical companies want us to believe recycling is the solution,” said California Attorney General Rob Bonta, who filed the California suit. Addressing a New York University symposium on Plastics and Human Health in September last year, Bonta spoke of the “myth” of recycling. “It’s a farce, it’s a lie, it’s a deceit,” he said.

“There is no plastic recycling at scale though they want you to believe different. Only five percent of U.S. plastic waste is actually recycled. Ninety-five percent goes into our environment, our treasured ocean and beloved streams, to landfill or is incinerated. It’s not recycled,” Bonta added.

University of California-Irvine

The Missouri case, Rodriguez et al. v. Exxon Mobil Corporation et al., is still pending.

On January 6, ExxonMobil filed a defamation lawsuit against Bonta and several environmental groups, including the Sierra Club, for statements regarding ExxonMobil’s recycling capabilities.

ExxonMobil is the world’s largest producer of plastic polymers used to manufacture single-use plastics.

ExxonMobil has also been one of the best-represented fossil fuel companies over the course of the international plastics treaty negotiations, sending 14 delegates, according to analysis by the CIEL and Greenpeace. The same analysis reveals that the American Chemistry Council, supported by DuPont and Dow, sent 22 delegates to the negotiations. In total, a record 220 fossil fuel and chemical industry lobbyists attended the last round of talks in Busan, which failed to achieve a deal.

“The danger here is delay,” Rachel Radvany, CIEL’s Environmental Health Campaigner who will attend the negotiations in Geneva, told DeSmog. “We’ve seen more and more plastics lobbyists show up at each round of negotiations. Their ultimate goal is to not allow true solutions to happen because it goes against their profit margins.”

According to Radvany, each delay in the negotiations is hurting people. “All the stages of the plastics lifecycle have really serious harms for human health, the environment, climate, biodiversity,” she said. “Every chance the lobby gets, they delay things, and every delay means more people are impacted and hurt by plastics.”

Overall, the seven largest plastic-producing firms in the world are fossil-fuel companies, which increasingly see plastic production as a highly profitable revenue stream at a time when the energy and transportation sectors are beginning to turn away from fossil fuels.

Recent oil and industry expenditures on plants capable of manufacturing new plastic materials is estimated to have been around $400 billion.

But producing plastic is also a major contributor to climate change. According to the World Economic Forum, the production of four plastic bottles alone releases the same amount of greenhouse gases as driving one mile in car.

A spokesperson for DuPont told DeSmog that the company does “not comment on pending litigation.”

ICCA, ExxonMobil, Chevron, Dow, and the American Chemistry Council did not respond to requests for comment by DeSmog.

“What’s needed to solve the plastics crisis is to take a step back and focus on protecting human health and the environment, and use that as a guiding frame for those solutions,” Radvany said. “So when you focus on recycling without addressing both the upstream toxic impacts, and also climate impacts, you’re never going to get to a true solution.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts