This article has been translated into Portuguese. You can read it on DeSmog here.

Food and agriculture will be under the spotlight at the upcoming round of global climate negotiations in northern Brazil.

Representatives from nearly every nation will gather from 6-21 November in Belém, a regional capital and gateway to the Amazon, with most countries far off target to deliver deep cuts to carbon emissions — the only way to halt the worst impacts of catastrophic climate change.

Some food and climate groups hope this thirtieth annual Conference of the Parties (or, COP30) summit can be a game changer for reforming food systems, which emit around a third of all greenhouse gases.

After all, Brazil — which holds the presidency of COP30 — has a reputation for skilled diplomacy, and has made agriculture objective number three on the conference agenda.

At home, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has lifted millions out of hunger, and pledged to protect endangered ecosystems in the Amazon rainforest and Cerrado savannah while state-supported family farms that produce most of the nation’s food.

But Brazil is also home to the world’s two biggest meat companies, and a leading exporter of beef and grain. Advocates for ambitious food system transformation will have their work cut out in Belém, where they will run up against entrenched opposition led by Brazilian agribusiness, which has been preparing its lines of attack throughout 2025.

Sustainable Tropical Agriculture tops the list of misleading narratives that will be used to suggest Brazil’s agriculture sector can continue business as usual, alongside No Additional Warming (a favourite of New Zealand’s livestock sector), and the evergreen Fossil Fuels are the Real Problem.

These concepts are designed to deflect pressure on food and farming to cut its climate pollution. The sector produces a cocktail of harmful and potent climate-heating emissions — from the nitrous oxide emitted by fertilizers, to the rising volumes of methane released from the digestive tracts of the world’s 3.5 billion cows, sheep, and goats.

Campaigners have described slashing methane from agriculture — the largest source of this potent planet-warming gas — as “the fastest and most cost-effective lever available to slow warming within our lifetimes”. The best way to pull this “emergency brake,” according to peer-reviewed science, is to consume less red meat — particularly in rich and middle-income nations.

But in Belém, agribusiness will insist that it is, in fact, the solution to climate change. To keep any mention of dietary change off the table, delegates from Brazil, the United States, and other livestock producer nations will downplay agriculture’s impacts, argue for technical solutions that will not reliably reduce emissions, and cast binding regulation of their industry as a threat to human health, prosperity, and well-being.

In a move welcomed by civil society and policymakers, the Brazilian COP presidency has championed “Information Integrity” at this summit to fight back against the tidal wave of climate mis- and disinformation. But agriculture’s greenwashing is harder to spot.

Here are eight arguments to be ready for in Belém:

Regenerative Agriculture

Served with: grass-fed beef, regenerative grazing, carbon farming, carbon positive

Free from universally accepted definitions or standards, the term “regenerative agriculture” — which broadly references environmentally friendly farming practises that can lead to increased storage of carbon in healthy soils — is a firm favourite in the net zero plans of polluting firms like McDonalds and Cargill.

It’s the subject of no fewer than 27 panels scheduled for the climate summit’s “Agrizone Pavilion” (one of several spaces holding themed events on the sidelines of the official negotiations), which is hosted by Embrapa, Brazil’s public agriculture research body, and sponsored by both Nestlé and pesticide firm Bayer.

The cropland practices loosely grouped under “regenerative,” such as organic and no-till farming, have benefits that do include long-term storage (or sequestration) of carbon in soil, along with boosting biodiversity.

However, a growing body of science has found that carbon sequestration in soil can offset at best a tiny fraction of the agriculture sector’s emissions.

The beef industry, in particular, likes to insist that regenerative cattle grazing and manure management can significantly lower the sector’s carbon emissions — which are roughly equivalent to the entire nation of India.

At past climate summits, organizations like the Protein Pact, a lobby group for the U.S. meat industry, have stressed the environmental gains mady by flagship ranches to suggest that intensive cattle farming is synonymous with sustainability and nature protection.

But meat’s outsized contribution to methane emissions leaves scientists in no doubt of the industry’s impacts — and how to tackle them.

In a 2024 survey of 200 experts, published by the Harvard Animal Law and Policy Program, 85 percent agreed that “animal-sourced” foods must reduce in the diets of rich and middle-income nations to bring about a 50 percent drop in livestock’s greenhouse gases by 2030, to stay within the climate goals agreed in Paris.

Note: Touting regenerative credentials also holds financial promise for agribusiness. Recent changes to the Paris Agreement have opened carbon markets to “soil-based credits,” which are now being traded under UN markets.

Tropical Agriculture

Often paired with: regenerative agriculture, climate-neutral, carbon offsets

Brazil’s “special envoy for agriculture,” Roberto Rodrigues, will come to COP30 ready to persuade negotiators that his country can take the lead in “low-carbon tropical agriculture.”

This Latin American twist on regen ag is used to suggest that a combination of warm-region soils and farming that integrates crops, livestock and forests, can absorb enough carbon to offset the methane generated by Brazil’s 238 million head of cattle.

In the lead up to the summit in Belém, major agriculture polluters have invoked tropical agriculture to make “carbon neutral” claims. Among them is Brazilian meat giant JBS, which had greater methane emissions in 2024 than ExxonMobil and Shell combined.

The scientific underpinning for this idea comes largely from Brazil’s state research agency Embrapa. Its “low-carbon” and “carbon-neutral” beef labels are now central to the industry’s marketing.

But independent research shows soil cannot absorb enough methane to offset livestock emissions in the region. “Emissions from livestock can be reduced,” says leading soil scientist Pete Smith. “But any claims that soil carbon could be increased to anywhere near the extent to offset emissions is preposterous – and not supported by the evidence.”

Other experts question elements of Embrapa’s methodology, saying it does not sufficiently account for the fact that most Brazilian pastures are created by clearing forest, which releases far more CO₂ than new trees can recapture.

Claudio Angelo, the chief communications officer at Climate Observatory, a coalition of climate NGOs, agrees that Brazilian farming has made improvements that can sequester carbon on a limited scale — by recovering degraded pasture, managing grazing, and integrating agro-forestry into cattle farms.

But to call the sector highly sustainable based on this would be “intellectual dishonesty,” he recently told Bloomberg.

Angelo points to the wider context. Brazil’s methane footprint has risen 6 percent since 2020, and agriculture drove over 74 percent of its total emissions in 2023. The expansion of croplands and cattle operations has also driven the loss of 97 percent of native vegetation over the past six years.

The cheerleaders of tropical agriculture insisting that their sector can continue to grow are out of step with the scientific consensus. A September 2025 paper published in the peer-reviewed journal One Earth found that current food system trends present an “unacceptable risk,” and prescribes changes to diets in all scenarios to stay within a livable climate, avoid tipping points past which major ecosystems cannot recover.

“To align with the Paris Agreement, absolutely huge reductions in feed production (including grazing) and animal-sourced food production would be required in this region,” said Oxford University climate and food systems scientist Helen Harwatt in an email. A “massive reduction in beef consumption” is also needed, she said, noting that Brazilians eat 20 percent more beef than citizens in the U.S, the world’s leading beef producer.

Yet if a recent COP30 position paper from the Brazilian Agribusiness Association (ABAG) is anything to go by, the trade group will be promoting its industry at the summit as a “low-carbon agriculture leader” — and will make no mention of the need to reduce livestock.

In response to questions, Embrapa stated in an email that “emissions related to deforestation are embedded in the carbon calculator over a 20-year timeframe,” adding that “the protocols [Low-Carbon and Carbon-Neutral Beef] are scientifically grounded and follow metrics recognized by the best available science.”

No Additional Warming

Often associated with: climate neutrality, GWP*, tropical agriculture

The subject of how to best measure methane emissions is likely to come up frequently in Belém, as nations with long-standing, large, and highly polluting livestock industries attempt to lock in methodologies that work in their favour.

Their tool of choice is GWP* or “global warming potential star.” Used at a global scale, GWP* can be a helpful metric for comparing the growth in emissions of short-lived heat-trapping gases like methane with the impacts of long-lived CO2. The controversy arises when GWP* — which is not used by the IPCC — is applied by a nation or corporation to itself. This leads to dramatically understating the emissions of large meat and dairy producers, while small increases elsewhere are punished.

Promoters of GWP* include powerful U.S., Australian, and Latin American industry groups along with the Oxford University academic Myles Allen, who first developed the metric. This year, for the first time, its proponents include governments — most recently New Zealand, which just enshrined GWP* into its domestic climate goals, thereby weakening its target for cutting methane pollution.

Called an “accounting trick” by critics, and dubbed “fuzzy methane maths” in a 2021 Bloomberg Green headline, researchers warn that adopting GWP* will disguise rising methane emissions, allowing big polluters to claim “climate neutrality” without cutting herd sizes or methane output.

Environmental scientist and economist Caspar Donnison likens GWP*-backed claims of climate neutrality to “claiming you’re fire-neutral because you’re pouring slightly less petrol on the blaze.”

A global group of climate scientists has publicly advised against adopting GWP* as a common metric on the grounds that it “creates the expectation that current high levels of methane emissions are allowed to continue.”

Oxford’s Allen, meanwhile, has called COP30 an “opportunity to “reframe climate policy” around alternative metrics like GWP*. In response to a request for comment, Allen said in email, “I think corporate and national climate claims should be informed by their impact on global temperature. I don’t mind how people calculate this, provided they do so accurately.”

Agribusiness trade groups in Brazil have picked up the baton, adding GWP* to their tropical agriculture toolkit, and Embrapa’s support for the metric is growing.

Bioeconomy

Often paired with: circular economy, biogas, biofuels, socio-bioeconomy

Much like regenerative agriculture, the term “bioeconomy” encompasses varied ideas for transforming production and consumption to make economies run in harmony with nature.

The term has taken on an altogether different hue, however, since it become a byword for green growth in Brazil and Europe, embraced by both agribusiness and government. Critics say they have hijacked the term to put a green spin on the expansion of destructive farming.

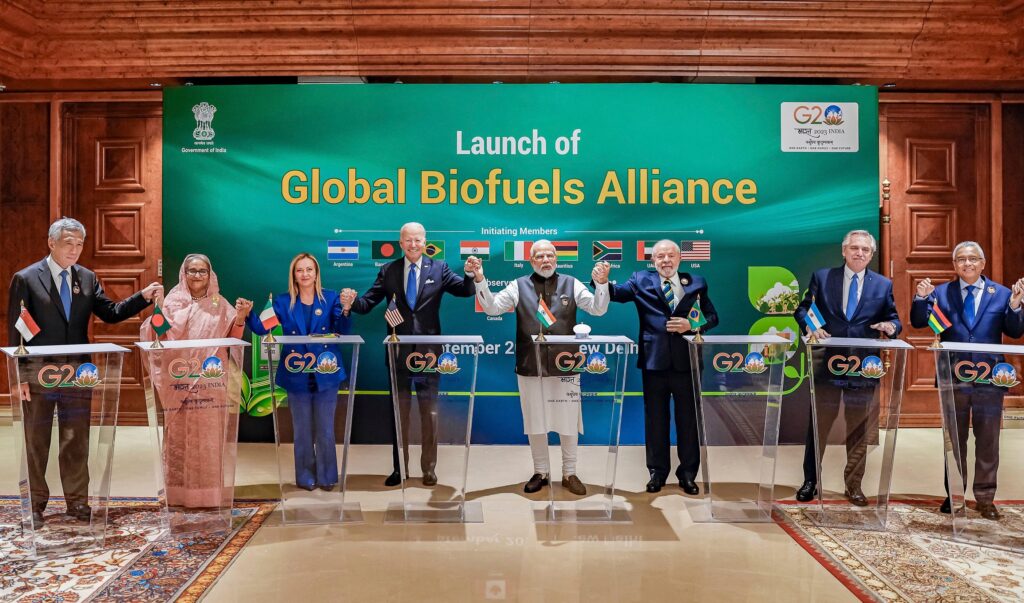

In the hands of corporations such as Cargill and dairy firm Arla, bioeconomy has morphed into a byword for a set of controversial, supposedly “green” fuels, such as so-called “biofuels.” Typically, biofuels refers to liquid fuels produced from organic materials (termed “biomass”), ranging from corn-based ethanol, a gasoline additive, to biodiesel from soybean oil. In the U.S., animal fats from meat processing plants are another major feedstock for biofuels, according to the Energy Information Agency.

Environmental scientists and campaigners have strongly critiqued biofuels because their production at scale requires using vast large tracts of land for monoculture crops of sugar cane and soy, which can lead to deforestation and biodiversity loss, as well as create competition with food crops.

Meat giants such as JBS, as well as food multinationals like Cargill, are also expanding into biogas: methane gas captured from sources such as manure or decomposing crop waste. Advocates for biogas are attempting to brand it as “clean” energy that may become a viable substitute for natural gas-fired power. However, it’s not yet clear whether biogas can be produced at industrial scale, with one recent analysis suggesting it may replace no more than seven percent of gas-fired power.

Worse still, since biofuels are produced from organic matter, they still release greenhouse gases when burned. An October study by advocacy group Transport and Environment found that for every unit of energy biofuels create, they emit 16 percent more CO2 than the fossil fuels they replace, due to the associated impacts of farming and deforestation.

As a major producer of ethanol from sugar cane, Brazil will bet big on bioenergy at the climate summit. According to a leaked document seen by The Guardian, Brazil plans to champion a global pledge to quadruple what it insists are “sustainable fuels,” chiefly biofuels and biogas.

We Feed the World

Often paired with: efficiency, emissions intensity, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), nutrition, “Brazil is only just off the hunger map”

The meat industry put this claim front and centre in its lobby plan for COP28 in Dubai, and it’s likely to make a comeback this year at COP30, particularly around Brazil’s anticipated launch of the “Belém Declaration on Hunger and Poverty”.

Agribusiness will employ this argument to suggest that any attempt to regulate the industry in line with science-based recommendations to safeguard the climate will make the poorest go hungry.

This claim hides an inconvenient truth: The planet already produces 1.5 times more food than it needs, yet hunger persists because of waste, poverty, and inequality — exacerbated by rising climate impacts.

Hunger is solved by politics and good policy, not production. While animal agriculture remains vital to healthy diets in some parts of the world, research shows that expanding industrial meat and dairy has done little to improve food security in low-income nations. Instead it is fuelling over-consumption in wealthier countries, where excess intake of meat (especially red and processed meats) has been linked to ill health.

Around 50 percent of maize and 75 percent of soy goes to animal feed, not people. Climate scientists and the EAT-Lancet Commission have stressed that cutting meat production in high-income countries would free up vast areas of cropland for grains and pulses that could feed many more people, with far fewer emissions.

A 2016 study showed that it is smallholder farms that supply the majority of food in the regions that are home to the highest numbers of people going hungry, producing more than 70 percent of calories in Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia.

When Brazil exited the UN hunger map — rightly celebrated as a huge step forward — its success came not from agribusiness exports, but from the state’s local food policies and investments in small farmer support programmes.

The EAT-Lancet Commission — which looked at how to feed all the world’s people a healthy diet without breaching planetary boundaries — has proposed a diet richer in whole grains, legumes, and seeds for protein. The commission’s landmark 2019 report suggested that people should eat an average of 50 percent less red meat in all but two regions of the world.

Other studies have confirmed that reduced consumption of meat would be a global win-win-win by reducing climate-heating pollution, conserving biodiversity, and improving human health.

As climate changes’s impacts worsen, the real challenge, according to University of Texas professor Raj Patel, lies in how to channel funds to more resilient and diverse “agroecological” systems, which receive a fraction of the financial support provided to industrial agriculture, rather than by expanding factory farming under the guise of feeding the world.

Big Ag Is Progress and Development

Often coupled with: economic development, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Scan Brazilian radio and social media during the summit, and you may hear the catchy strains of “agronejo”, a genre of country music with twists of hiphop and electronic pop, which paints agriculture as synonymous with wealth, prosperity, and power.

Agronejo is just one example of the agribusiness industry’s powerful cultural PR campaign in Brazil, where it has it’s own TV channels, programmes and publishers, as well as dedicating resources to “build empathy for producers” among children in Brazilian schools via textbooks, audiobooks, and teacher resources (a tactic also used in Ireland and the U.S).

As the climate conference approaches, JBS is sponsoring COP30 content in major Brazilian newspapers including Valor Econômico, Estadão, and O Globo.

This line of mythmaking casts agribusiness as a modernising force throughout the global South. In JBS’ recent announcement about expansion into Nigeria, it stated that its factories will create jobs and bolster food security — claims disputed by local food system experts.

By contrast, small producers in the global South are framed as unhygienic, and much more polluting than industrial-scale meat and dairy operators, which claim their carbon emissions are much lower per kilo of milk or meat produced.

This arguments subtly shifts the emphasis from the sector’s total greenhouse gas emissions — where high and upper-middle-income nations sit at the top of the list, far outweighing the 10 percent of pollution produced by “inefficient” low-income nations,

Evidence suggests that agribusiness claims about wealth and jobs also ring hollow. A 2025 study showed that even though farmers in the global South produce 80 percent of food consumed globally, profits from agriculture are disproportionately captured by governments and companies in the global North, via high-profit activities such as the marketing and distribution of food.

In the run-up to COP30, which small farmers are billing “the agribusiness summit”, Brazilian civil society is holding a People’s Summit that will compete with Big Ag’s shiny PR for tech-driven solutions. Focused on an alternative vision of agriculture, the People’s COP will champion locally-grown and sourced foods, and the power of Brazil’s ecologically-minded smallholder farmers to nourish Brazil’s population.

Efficiency Is Enough

Often paired with: emissions intensity, innovation, new technologies, producing “more with less”, “We feed the world”

Global North dairy farms, which send large numbers of delegates to climate summits, are going to press home the argument that its portion of climate crisis can be fixed through efficiency, not transformation.

By producing “more with less,” they say, carbon emissions can fall even as supplies of milk and butter continue to grow. They argue this is possible thanks to technologies such as feed additives that reduce dairy’s “emissions intensity”: the amount of methane created per pint of milk produced.

On close inspection many of the bold carbon reduction targets announced by dairy firms are of intensity, not absolute pollution, which continues to grow. The latest industry figures show, while these groups touted emissions intensity reductions of 11 percent from 2005 to 2015, emissions of the dairy industry rose overall by 18 percent — due to herd sizes growing by nearly a third.

Danish dairy giant Arla, New Zealand’s Fonterra and China’s Mengniu are among those to have set reduction targets for their Scope 3 (supply chain) missions on an intensity basis only.

Unless limits are placed on production — which agriculture is hellbent on avoiding at all costs— there is no guarantee that more efficient production will bring down pollution.

That’s because making something more efficient usually means you use more of it, not less — a phenomenon known as the Jevons paradox. Dairy companies in Ireland, for example, pollute less per unit of milk, but they have done so by scaling up production. And the money saved was ploughed into increasing herd sizes. The result? According to the latest available figures dairy’s methane emissions continue to rise.

It’s a testament to the power of the livestock lobby that the “solutions to climate change” which took centre stage in the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO)’s long-awaited 2023 “Pathways to lower emissions” livestock report were … “technology” and “voluntary efficiency”, which would allow the sector to keep growing. This conclusion ignored the peer-reviewed science that consistently comes down in favour of prioritizing government policies that shift diets away from animal products, with technology playing a minor role.

Fertilizer and pesticide giants — which are also under pressure to lower both climate-heating emissions and environmental impacts use efficiency-based arguments too, such as touting drones, precision spraying, and chemical-coated seeds as green solutions.

However, agrochemicals are key drivers of ecological destruction and the pollution of soil, air and water, and are most heavily used to support production of damaging monocrops, which are at the core of industrial animal agriculture systems.

While small efficiency improvements matter, experts warn they are no substitute for absolute cuts in methane, fertilizer, and land use change. “Efficiency” may be good for business—but not for the planet.

Fossil Fuels Are the Real Problem

Often paired with: “Agriculture is a solution,” “Agriculture is unfairly villainized,” “We are making great strides in reducing our emissions”

When challenged on agriculture’s climate impacts, farm lobbies have a history of deflection: pointing the finger of blame elsewhere.

Ahead of the climate summit, Latin American trade bodies are trying to get themselves off the hook by shifting the blame onto the fossil fuel industry. One major trade group has bemoaned how recent conferences have had a “distorted” focus on agriculture over “obvious sources of emissions”.

For its part, the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA) — which represents large producer countries — has declared that its goal in Belém will be to “remove [agriculture] from the dock of the accused.” In response to a request for comment, Lloyd Day, the Deputy Director General of IICA, said that while he would not characterise agriculture in this way, though he felt agriculture had been unfairly cast as a “villain” at climate discussions, such as the annual climate summits, when the sector was really “part of the solution.”

Theis tactic of deflecting to other industries has also been used by agriculture trade groups and industry allies in the U.S, which have argued that the sector’s contributions to the climate crisis pales in comparison to fossil fuel-guzzling sectors like transport. It mirrors classic “delay and distract” techniques used by the fossil fuel and tobacco industries, framing farming as a scapegoat even food systems consume at least 15 percent of all global fossil fuels in the forms of fertilizers, transport, plastics, and feed.

While coal, oil, and gas remain the largest contributors to climate change, emissions from food systems alone, if left unchecked, have the potential to take the world over 1.5 C.

The food system now has the unhappy mantle of being the largest driver of all other planetary boundary transgressions. ranging from forest destruction and the collapse of wildlife populations to the pollution of fragile fresh water supplies.

Agriculture also surpasses fossil fuels in its methane and nitrous oxide pollution — which together are responsible for more than a third of global warming to date.

By claiming fossil fuels are the “real culprit,” the industry diverts attention from its own footprint and stalls meaningful reform. Climate experts counter that tackling global warming requires confronting both sectors with equal ambition.

JBS, PepsiCo, McDonalds, and the New Zealand Government did not respond to requests to comment before going to press.

Additional reporting by Gil Alessi and Maximiliano Manzoni

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts