This story is published in partnership with Rolling Stone.

A cache of government documents dating back nearly a century casts serious doubt on the safety of the oil and gas industry’s most common method for disposing of its annual trillion gallons of toxic wastewater: injecting it deep underground.

Despite knowing by the early 1970s that injection wells were at best a makeshift solution, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) never followed its own determination that they should be “a temporary means of disposal,” used only until “a more environmentally acceptable means of disposal [becomes] available.”

The documents include scientific research, internal communications, and talks given at a December 1971 industry and government symposium. And they come from multiple federal agencies, including the EPA, the U.S. Department of Energy, and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

The documents show there may be little scientific merit to industry and government claims that injection wells are a safe means of disposal — putting drinking water and other mineral resources in communities across the country at risk of contamination, and jeopardizing local economies and public health.

The U.S. oil and gas industry produces 25.9 billion barrels of wastewater each year (or 1.0878 trillion gallons), according to the most recent data available, according to the most recent data available, a 2022 report from Groundwater Protection Council that relies on 2021 data. That’s enough to form a line of waste barrels to the moon and back 28 times.

This wastewater — variously referred to by the industry as “produced water,” “brine,” “salt water,” or simply “water” — comes to the surface naturally during extraction of oil and gas. Some 96 percent, 24.8 billion barrels, is disposed of by injecting it back underground.

In 2020, there were 181,431 injection wells (referred to in some regions as saltwater disposal wells or SWDs) in the United States, according to an EPA fact sheet — roughly 11 injection wells for every Starbucks across the country. If you drove from New York City to Los Angeles at 65 miles per hour and lined the highway with them, you would pass an oil and gas wastewater injection well every nine-tenths of a second.

These injection wells dispose of a complex brew of wastewater by shooting it deep underground. According to one oil and gas industry explanation of the wastewater disposal process, liquid waste is injected underground at high pressure into an “injection layer,” a targeted layer of rock containing a considerable amount of “pore space”: gaps between the rock grains that compose it. This injection layer fills up with the wastewater, while surrounding layers of impermeable rock act as seals to prevent the waste from leaking out.

But oil and gas industry wastewater can contain toxic levels of salt, carcinogenic substances, and heavy metals, and often far more than enough of the radioactive element radium to be defined by the EPA as radioactive waste. Radium has been described by researchers as a bone-seeker because it can mimic calcium and once inside the body may be incorporated into bones — it’s what killed the early 20th century factory workers known as the Radium Girls, who used a radium-based radioactive paint to make watches glow in the dark and kept their brushes firm by licking the tips.

“These contaminants pose serious threats to human health,” says Amy Mall, director of the fossil fuels team at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). “Every day in the U.S., the oil and gas industry generates billions of gallons of this dangerous wastewater.”

Other industries also use injection wells to dispose of dangerous waste, such as the pharmaceutical and steel industries, slaughterhouses, and pesticide manufacturers.

While the USGS has linked injection wells to damaging earthquakes, both the oil and gas industry and government regulators claim they are safe to use for wastewater disposal. But these historic documents suggest that they have long known otherwise.

Deep-well injection is “a technology of avoiding problems, not solving them in any real sense,” stated Stanley Greenfield, the EPA Assistant Administrator for Research and Monitoring, in a 1971 talk at the “Underground Waste Management and Environmental Implications” symposium in Houston, Texas. “We really do not know what happens to the wastes down there,” Greenfield said. “We just hope.”

A Hundred Years of Alarm Bells

Wastewater has plagued the petroleum industry since its earliest days in western Pennsylvania 150 years ago. For its first century, drillers directed wastewater into pits dug beside the well, or intentionally dumped it into ditches, streams, swamps, or bayous. In one instance in 1920s Mississippi, wastewater was stored in a wood-sided swimming pool for children.

The first allusion to disposal by underground injection appeared in a 1929 report from the U.S. Department of the Interior: “The disposal of oil-field brines by returning them to a subsurface formation, from the information thus far obtained, appears to be feasible in isolated instances.” However, the next lines warned: “Not only is there danger that the water will migrate to fresh-water sands and pollute a potable water supply, but also there is an ever-present possibility that this water may endanger present or future oil production.”

By the mid-20th century, the industry realized that injecting wastewater could be useful in another way: for pushing hard-to-reach oil lingering in some rock formations up to the surface. This technique, called waterflooding or enhanced oil recovery, generated a significant fraction of the oil produced in the U.S. from the 1950s through the early 1990s.

With the passage in 1972 of the Clean Water Act, industries were forced to stop dumping their wastes into rivers, where it poisoned wildlife, fouled fresh water supplies, and caused ugly slicks that occasionally caught fire. This directly drove massive growth in underground disposal, a transition captured in the EPA documents of the era.

“Little attention was given this technique until the 1960s,” stated a 1974 EPA report on injection wells, “when the diminishing capabilities of surface waters to receive effluents, without violation of standards, made disposal and storage of liquid wastes by deep well injection increasingly more attractive.”

In 1950, there were just four industrial injection wells in the United States, and in 1967 there were 110. That number would increase more than 1,000-fold in the coming decades, despite the concerns of some prominent early critics. In October 1970, David Dominick, the commissioner of the Federal Water Quality Administration (which would be merged into the EPA two months later), warned that injection was a short-term fix to be used with caution and “only until better methods of disposal are developed.”

Late the following year, in December 1971, some of the 50-odd speakers at the four-day “Underground Waste Management and Environmental Implications” symposium in Houston expressed optimism about injection wells. Vincent McKelvey, a USGS research director and the symposium’s keynote speaker, said he believed the subterranean earth represented “an underutilized resource with a great potential for contribution to national needs.”

Many more at the event, which was organized by the American Association of Petroleum Geologists and the USGS, were not so sure. In hindsight, the reservations they shared during the symposium are accurate predictions of injection well problems to come.

One Utah geologist warned that injecting chemical-filled waste deep into the earth could affect the strength of rocks and how they interact with one another. “The result could be earthquakes,” he said, that would create fractures which could channel waste out of the injection zone. A Department of Energy researcher said the disposal of radioactive liquid wastes, even in low concentrations, posed “a particularly vexing problem.”

A Wyoming law professor offered “not a cheerful” message: “If you goop up someone’s water supply with your gunk; if you render unusable a valuable resource a neighboring landowner might have recovered; or if you ‘grease’ the rocks, cause an earthquake, and shake down his house — the law will make you pay.”

USGS hydrologist Robert Stallman conjectured — with some accuracy, as it has turned out — that the consequences of injecting large amounts of liquid waste underground would include pollution of groundwater and surface water, changes to the permeability of rocks, cave-ins, earthquakes, and contamination of underground oil and gas deposits.

No one at the conference critiqued the practice of injection as meticulously as a USGS hydrologist named John Ferris.

“The term ‘impermeable’ is never an absolute. All rocks are permeable to some degree,” Ferris told the symposium. Wastewater would inevitably escape the injection zone, he continued, and “engulf everything in its inexorable migration toward the discharge boundaries of the flow system,” such as a water well, a spring, or an old oil or gas well.

While the advancing front of waste might initially cause wells and springs to surge with freshwater, the contamination “would become apparent at ever-increasing distances from the injection site,” he concluded.

“Where will the waste reside 100 years from now?” asked Orlo Childs, a Texas petroleum geologist, in his closing remarks. “We may just be opening up a Pandora’s box.”

“It is clear,” said Theodore Cook of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists, in his forward to a roundup of the symposium’s presentations in 1972, “that this method is not the final answer to society’s waste problems.”

‘Industry Attacked the Rules’

Initially, at least, the EPA seemed to heed these warnings. In a 1974 policy proposal, the agency echoed David Dominick’s concerns, stating in an internal memo that they considered “waste disposal by [deep] well injection to be a temporary means of disposal” until “a more environmentally acceptable means of disposal” became available.

In June 1980, the EPA began regulating injection wells under the Underground Injection Control (UIC) program. While this meant there would be federal oversight, the rules transformed a disposal technique once critiqued by the agency and with questionable scientific merits, into one that was now enabled by the country’s top environmental regulator. Immediately the EPA faced multiple lawsuits by industries, including oil and gas, mining, and steel, which complained underground waste injection regulations would cost them billions.

“Industry attacked the rules on the grounds that they were too complex and too costly,” observed a 1981 Oil & Gas Journal article.

The resulting settlement did away with some of the testing requirements related to injection wells, and reduced the number and frequency of the reports that industry must file. Industry also made a concerted and largely successful effort to wrest regulatory control of injection wells from the EPA and give it to states. The EPA has since given 33 states permission to regulate injection wells themselves, including Ohio, Texas, and Oklahoma.

“I think at best they had a back-of-the-envelope calculation as to the capacity of these formations to take this waste, at worst it was just a rubber stamp,” says Ted Auch, a researcher with the oil and gas watchdog Fieldnotes who has spent over a decade investigating the extent and impact of oil and gas industry waste production.

The 1980s nonetheless saw some critical government injection well research, despite eight years of generally pro-industry and anti-environmental protection policies under President Ronald Reagan.

A 1987 report from the EPA’s Kerr Environmental Research Lab in Ada, Oklahoma, found that “hazardous wastes are complex mixtures of materials” and “subsurface environments often take many years to reach chemical and biological equilibrium.” This made it “difficult to predict exactly the action or fate of wastes after their injection,” if not “nearly impossible.”

Another 1987 report, prepared jointly by the EPA and the Department of Energy and published by the National Institute for Petroleum and Energy Research in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, warned of several ways waste might escape the rock layer it had been injected into and move through the earth to contaminate groundwater, which is typically held in rock formations much closer to the surface. Waste, the report stated, could fracture rocks deep in the earth, “whereby a communication channel allows the injected waste to migrate to a fresh water aquifer.” The injection well itself could corrode, enabling “waste to escape and migrate.” Further, older oil and gas wells could provide “an escape route whereby the waste can enter an overlying potable ground water aquifer.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts

Since the early 2000s, when new technologies spurred the fracking boom, drillers have been able to tap into once-inaccessible rock formations for oil and gas, often located close to communities — and sometimes, as in the Denver-Julesburg formation in Colorado, or the Marcellus and Utica Shale formations in Pennsylvania and Ohio, right in the middle of them. In addition to the flood of wastewater that these wells create, with elevated levels of naturally-occurring salts, carcinogens, metals, and radioactivity, there’s a second waste stream unique to fracking: flowback, the toxic regurgitation of sand and chemicals shot down a well in the fracking process.

These fracking chemicals are specifically designed to generate cracks in rock, and to lubricate and fracture formations, in order to get at the oil or gas they hold. It’s entirely unknown how these chemicals react, and interact, in the high pressure, high temperature subterranean environment of the injection zone, says Anthony Ingraffea, an engineering professor emeritus at Cornell University who has spent his career studying the oilfield.

This ever-growing tsunami of oil and gas wastewater has to go somewhere, and most of it will continue to go to injection wells. “One might be tempted to believe that well construction designs, materials, and techniques on wells constructed decades ago were vastly different than those of today,” says Ingraffea. “This is false.”

America’s top environmental regulator vigorously defends reliance on injection wells, stating on its website that they have “prove[n] to be a safe and inexpensive option for the disposal of unwanted and often hazardous byproducts.”

In response to questions about the agency’s historic concerns about the long-term use of injection wells, EPA Press Secretary Brigit Hirsch says that the agency “is committed to supporting American energy companies and industry that are seeking permits for underground injection of fluids associated with oil and natural gas production,” in order to “[advance] progress on pillars of its Powering the Great American Comeback initiative.”

Early Warnings Realized

After 90 years of using injection wells to bury wastewater, including the past 13 years as the world’s biggest producer of oil and gas, the United States has a profound pollution crisis. The oil and gas industry and its regulators are facing a long-stalled reckoning on injection wells in both the courts, and the court of public opinion.

In May 2022, a rural Ohio oil and gas operator named Bob Lane filed a lawsuit in the Washington County Court of Common Pleas against area injection well operators, alleging these companies’ “infiltrated, flooded, contaminated, polluted” his oil and gas wells and property with waste containing hazardous materials “known or reasonably anticipated to be human carcinogens,” and “harming the commercial viability” of his “oil and gas reservoirs.” Defendants in the case include Tallgrass Operations, a Colorado-based energy infrastructure company, and DeepRock Disposal Solutions, a company formerly owned by Ohio state senator Brian Chavez, who chairs the Ohio Senate Energy Committee. The case is now before the Ohio Supreme Court and being followed closely by regional attorneys.

“We want to respect the process of the ongoing litigation, so we will not comment on it at this time,” says Tallgrass spokesperson John Brown.

Brown says his company adheres to Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) rules and that its injected wastewater is contained within its permitted injection zone and does not impact drinking water. “It’s important to note that underground injection is a long-established and proven method of disposal for many U.S. industries,” says Brown, “and that it plays an essential role in supporting the low-cost, reliable energy systems that are critical to millions of Ohio families and communities across the country.”

DeepRock has not replied to questions.

ODNR spokesperson Karina Cheung says the agency has suspended operations at six injection wells that present “an imminent danger to the health and safety of the public and is likely to result in immediate substantial damage to the natural resources of the state.” A 2023 ODNR report called this leakage “potentially catastrophic” and warned of “extensive environmental damage and/or aquifer contamination,” admitting that Ohio’s long history of oil and gas drilling has left “numerous penetrations that may serve as pathways for fluid to migrate.” In November, Buckeye Environmental Network, an Ohio advocacy group, filed a lawsuit in Ohio’s Tenth District Court of Appeals against ODNR for permitting a pair of injection wells operated by DeepRock that would be within two miles of a zone meant to protect the source of drinking water for Marietta, Washington County’s largest city.

“I can think of nothing more important than to protect the city’s water,” says Marietta City Council President Susan Vessels. “There is no just looking the other way, I want to help our city avoid an environmental catastrophe, which I believe is eventually going to happen if we continue down this path.” In October, the council passed a resolution urging Ohio state legislators to introduce legislation imposing a three-year moratorium on new injection wells in Washington County.

Meanwhile, in Oklahoma, a stunning expose co-published in October by ProPublica and the Oklahoma-based newsroom Frontier documented a “growing number of purges,” where oil field wastewater has been injected at “excessively high pressure” and cracked rock deep underground, freeing it to travel uncontrolled for miles, sometimes returning to the surface via abandoned wells. In one instance, a spew of brine from a defunct well contaminated a watering hole for livestock, killing at least 28 cows.

The story features Danny Ray, a whistle-blowing former state regulator and long-time petroleum engineer, who is worried that given Oklahoma’s vast number of unplugged oil and gas wells, the state is ripe for more of these sorts of disasters. However, the Oklahoma Corporation Commission, the state’s oil and gas regulator, discounted Ray’s concerns, saying in a statement that it remains “committed to protecting Oklahoma and supporting the state’s largest industry to perform its role in a safe and economic manner.”

“These goals are not mutually exclusive,” according to the agency.

In West Texas, Bloomberg reported in September, a growing number of the state’s over 2,000 defunct oil and gas wells — locals call them “zombie wells” — are spouting unpredictable geysers of fracking waste. One blowout in Crane County shot wastewater 100 feet high into the air in 2022, releasing around 24 million gallons of toxic fluids before it was capped about two weeks later.

A spokesperson with the Railroad Commission of Texas, the state’s oil and gas regulator, told Bloomberg that it had instituted a set of protective new rules regarding oil and gas wastewater injection wells, but recognized “the physical limitations of the disposal reservoirs” as well as the risks to oil production and fresh water.

Just last month, Inside Climate News reported on a new lawsuit filed by a Crane County landowner claiming “catastrophic impacts” from injection well blowouts.

The impacts of injection well leakage and blowouts have become visible from space. In a 2024 study using satellite observations, a team of Southern Methodist University scientists found that so much wastewater has been injected underground that it has raised land in one area of the Permian Basin by 16 inches in just two years, and created a high-pressurized underground lake that will lead to more sky-high wastewater gushers. “We have established a significant link between wastewater injection and oil well blowouts in the Permian Basin,” the authors wrote in the academic journal, Geophysical Research Letters.

Once “a little cottage industry of mom and pops,” injection wells have become “a much bigger business,” says Kurt Knewitz, a consultant who runs an injection well information site called BuySWD.com. A case in point, says Knewitz, is Pilot Water Solutions, which operates injection wells in Texas and is a division of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.’s Pilot Travel Centers, the multinational energy and logistics company owned by Warren Buffet.

“You look at the Permian Basin and you think it’s a huge oil play, but it produces three to four times as much produced water as oil,” says Knewitz. “So the Permian is really a produced water play that on the side produces some oil and gas.”

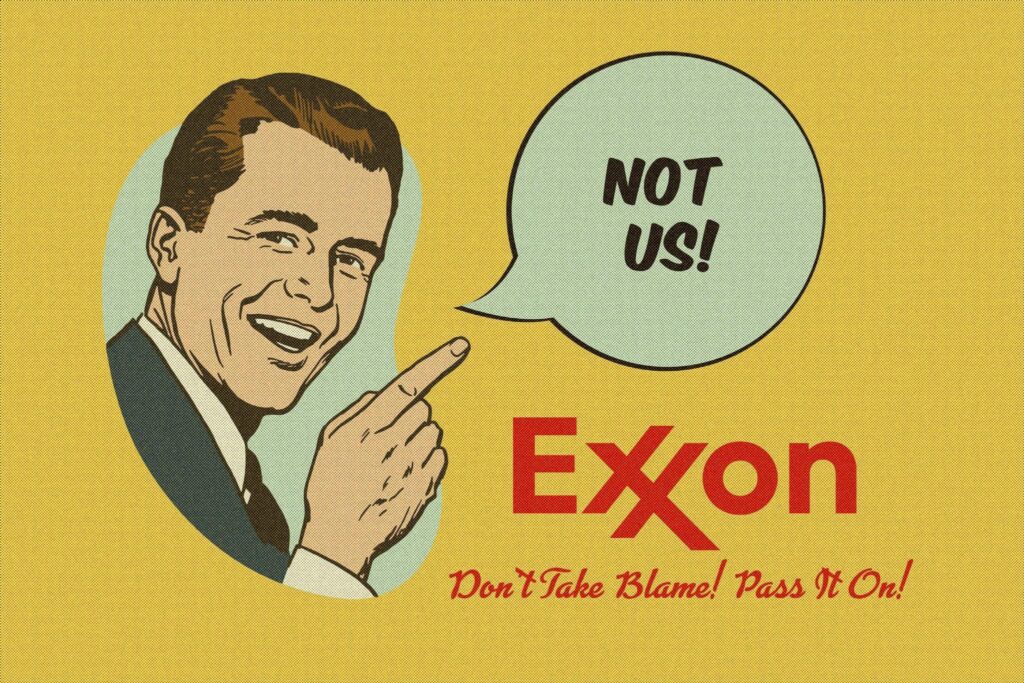

Still, the industry has not acknowledged the toxic reality on the ground, and continues to defend its favorite waste disposal practice. A recent report from the American Petroleum Institute (API), the nation’s largest oil and gas lobby, states that injection wells are “safe and environmentally reliable” and “serve a vital role by supporting the responsible and sustainable development of O&G resources.”

The API did not respond to specific questions regarding the merits of early critiques of injection wells, or whether they remain valid today. “Our industry is committed to the responsible management of produced water,” spokesperson Charlotte Law said in the group’s response. “Operators continuously invest in advanced treatment technologies, recycling, and reuse practices to minimize freshwater use, protect ecosystems, and ensure safe operations.”

The USGS and DOE did not respond to questions for this story.

Advocacy groups that have spent decades tracking the EPA’s oil and gas waste rules point out that the business model of the U.S. fracking industry depends on operators being able to get rid of waste cheaply.

“The inadequate regulation and enforcement of waste disposal wells across the country represents a financial giveaway to the oil and gas industry,” says the NRDC’s Mall, with NRDC. “Experts have known for generations this method threatens the environment.”

For queries about republishing this story, please contact [email protected].

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts