The scars of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans that remain nine years later are a reminder of the city’s vulnerability to rising tides and storm surges. Both Katrina and Rita, a hurricane that followed just weeks later, washed away miles of coastal marshland, the state’s first line of defense from storms.

The landscape in Plaquemines Parish’s Braithwaite neighborhood is still that of a ghost town two years after Hurricane Isaac hit, underscoring the need to restore the coast.

Blighted homes in New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward on August 22. © 2014 Julie Dermansky

Home in Braithwaite, Louisiana destroyed by Hurricane Isaac. ©Julie Dermansky

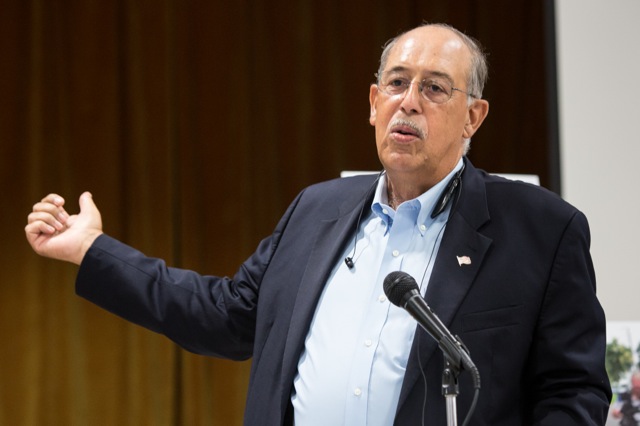

The day after Hurricane Katrina’s nine-year anniversary on Friday, former Lt. General Russel Honoré and his Green Army held a commemorative breakfast. The army, a coalition of environmental and social justice groups, reflected on work they had done during the last legislative session and discussed their path forward. Saving Louisiana’s coast was on top of the agenda.

Former Lt. General Russel Honoré speaking at the Green Army Katrina Anniversary Commemorative Breakfast, held at Xavier University in New Orleans. ©2014 Julie Dermansky

Interior of Club Desire in New Orleans’ 9th Ward. © 2014 Julie Dermansky

Louisiana is faced with dangers brought on by climate change, paired with coastal erosion accelerated by human activities including water diversion projects and damage done by the oil and gas industry.

There is a land loss on the Louisiana coast of approximately one football field every 38 minutes according to the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources. Their figures are based on numbers released by the United States Geological Survey.

“At current land loss rates, nearly 640,000 more acres, an area nearly the size of Rhode Island, will be under water by 2050,” The Louisiana agency says.

Plaquemines and Jefferson Parrish have waged multiple lawsuits against oil and gas companies alleging they broke the rules required in the permits allowing them to work in the wetlands, while others operated without permits at all, hastening coastal erosion.

The permits require the companies to restore the area they damaged to its original condition when work is complete — a condition overlooked for years by industry.

The lawsuits aim to recover funds needed to repair and restore the coast. The Parish lawsuits target individual companies citing specific wrongdoing, coinciding with the damage they allege was caused.

The Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority-East (known as the levee board) waged its own lawsuit against the 97 oil and gas companies. They claim all of the companies contributed to damage to the coast that has weakened New Orleans’ flood protection.

Their suit follows the same argument: industry failed to restore the land they used to its original condition, as required by permits issued in order for them to do the work.

Blighted home in New Orleans’ 9th Ward with illegally dumped tires. ©2014 Julie Dermansky

An illegal dump behind an abandoned building in New Orleans’ 9th Ward. ©2014 Julie Dermansky

None of the lawsuits try to hold industry responsible for all of the damage to the coast, just their share of the damages. What that amount is has not been clarified yet.

“Failing to restore oilfields that had been destroyed by the pits and canals that are a part of oil and gas extraction, and leaving polluted land and water in their wake, is against the law,” John Carmouche, one of the lead lawyers for the parishes, told the Baton Rouge Advocate.

“Enforcement of those regulations has been lax or non-existent, relying largely on self-reporting by the companies doing the work. The law is clear and the industry needs to be held accountable,” Carmouch said.

The Louisiana Oil and Gas Association has lobbied against all of the lawsuits, trying to get legislators to pass bills that will squash the lawsuits before they advance.

Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal is openly opposed to the levee board suit, and signed SB 469 into law in June. The bill was written in an attempt to remove the levee board’s authority to sue the oil companies. It is “legislation that will help continue coastal restoration work and stop unnecessary, frivolous lawsuits,” according to Jindal’s website.

Before the bill passed, legal experts and Louisiana’s Attorney General Buddy Caldwell warned that, once singed into law, SB 469 could open the door for BP to challenge a number of lawsuits waged against the company by taking away many plaintiffs’ right to sue. After a four day delay, Jindal signed the law anyway.

Gov. Jindal’s brother, Nikesh Jindal, is an associate of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, a law firm representing BP, a fact exposed by Lamar White, Jr. in his blog, suggesting a major conflict of interest.

The lawyers representing the levee board don’t believe the new law can stop their suit. But the board is faced with another obstacle. Jindal has been stacking the board with members who are against the suit. After the next appointments are made, there is a chance the board will have enough members against the suit that they will call it off themselves.

Jindal started this process by not reappointing John Barry when his term was up. Barry, the former head of the levee board and a leading voice for the lawsuit, believes that if the oil and gas companies don’t pay for the damage they have done, there will not be enough money to protect the coast.

“Without the lawsuit, the demise of the coast is inevitable,” Barry told DeSmogBlog.

John Barry speaking at the Green Army Katrina Anniversary Commemorative Breakfast, held at Xavier University in New Orleans. ©2014 Julie Dermansky

At the commemorative breakfast, Barry pointed out, the oil and gas industry helped craft 19 bills to squash the levee board’s lawsuit and the Green Army managed to block 18 of them. The bill that did pass is unconstitutional and won’t hold up in court, the group says.

The estimated tab of Louisiana’s master coastal restoration plan, approved in 2012, is more than $50 billion over 50 years.

“Of that, about $1.2 billion is expected from a settlement with BP over the 2010 oil spill and a revenue-sharing bill will contribute some $600 million starting in 2017,” reported the National Journal.

So where will the missing money come from?

Billy Nungesser, Plaquemines Parish president, doesn’t see a problem with finding the money to restore the coast.

“Plaquemines Parish came up with their own plan that costs less than the state’s master plan,” he told DeSmogBlog.

Billy Nungesser, Plaquimines Parish President next to Congressman Steve Scalise at a “town hall” meeting held by Rush Radio in Covington, Louisiana. ©2014 Julie Dermansky

“There would be enough money from BP to restore the coast. Nobody wins if we fight this out in court,” Nungesser says. “The biggest enemy is ridiculous litigation cost and politicians who want to spend the BP money on things other then coastal restoration.”

Nungesser is against all of the lawsuits, although he signed on to the ones where his parish is the plaintiff.

“The lawsuits are distracting,” he said. Nungesser believes industry is a good partner with the state. Though an outspoken critic of BP during the oil spill cleanup, Nunngesser has demurred.

“There is nothing we have asked the oil industry to do that they haven’t done,” Nungesser says. “We’ve got one chance at saving this coast,” he acknowledged, adding that, “We are going to get enough money from BP to begin the process — God help us if we don’t.”

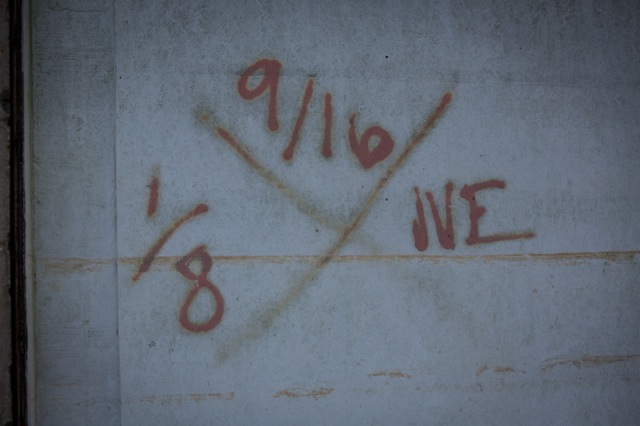

Marking left on a home by a rescue worker during Katrina’s aftermath in New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward. ©201 4 Julie Dermansky

Yet BP has done a remarkable job not paying for the damage they caused following the 2010 spill. They filed a petition to the U.S. Supreme Court against a lower New Orleans court’s settlement they helped craft.

The latest setback to victims of the spill came when a judge ruled in favor of BP in an interpretation of medical settlement payments. Those not diagnosed before 2012 by a doctor are not able to qualify for what is called “Specified Physical Condition” payments.

Their cases now fall under “later-manifested” cases and will be heard after the main cases are settled, adding years to the time those victims might receive compensation.

If there is not major coastal restoration soon, all of the city’s natural protection will be gone.

Satellite images illustrate the damage done over the last 30 years. New Orleans stands to become beachfront property with little chance of surviving as climate change accelerates.

Blighted structures in Press Park, a public housing project in New Orleans’ 9th Ward built on top of a Superfund site. © 2014 Julie Dermansky

Blighted commercial space in New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward. © 2014 Julie Dermansky

Part of the foundation of a home in New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward. ©2014 Julie Dermansky

Blighted public housing development left in ruins since Katrina in New Orleans’ 9th Ward. © 2014 Julie Dermansky

Blighted home in New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward. ©2014 Julie Dermansky

Blighted home in New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward. ©2014 Julie Dermansky

Blighted home in New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward. ©2014 Julie Dermansky

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts