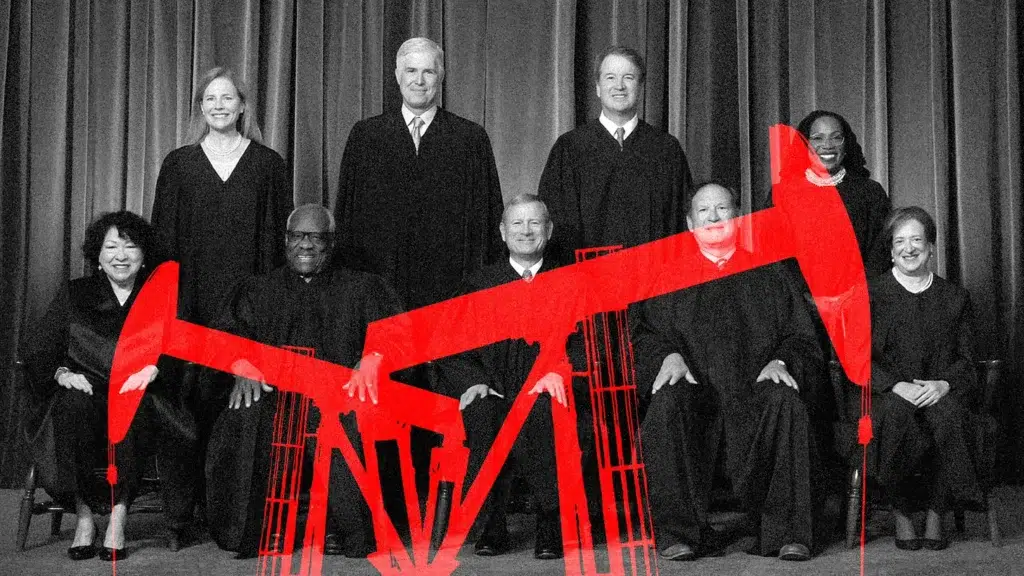

Here at DeSmogBlog, and around the environmental and liberal political blogosphere, there is great concern about “Astroturf” organizations—groups that pose as real citizen movements or organizations, but in fact are closely tied to corporations or special interests. The “fake grassroots” has been a major issue in the climate debate in particular, where groups like Americans for Prosperity, closely tied to the billionaire Koch Brothers, have sought to mobilize opposition to cap-and-trade legislation.

One obvious goal of astroturfing is to shape public policy, and public opinion, in a manner congenial to corporate interests. And indeed, the outrage over astroturfing in a sense presumes that this activity actually works (or else, why oppose it).

Yet there have been few scientific tests of whether the strategy does indeed move people—in part, presumably, because doing a controlled experiment might be hard to pull off. That’s why I was so intrigued by a new study in the Journal of Business Ethics, which attempts to do just that.

Charles H. Cho of the ESSEC Business School in France, and his colleagues, set up a study in which they created (ironically) fake Astroturf websites related to global warming—as well as fake grassroots websites on the same issue–and tested over 200 college undergraduates on their responses to them. To ensure a strong experimental design, only a few things were varied about these websites–what they claimed about the science, and what they disclosed about their funding sources:

The website for each condition, respectively, consisted of a ‘‘Home page’’ with links to five other pages pertaining to global warming and the organization’s activities. In the grassroots condition, these were labeled as ‘‘About us,’’ ‘‘Key issues and solutions,’’ ‘‘Why act now?’’ ‘‘Get involved!’’ and ‘‘Contact us.’’ Similarly, in the astroturf condition, the pages links were labeled as ‘‘About us,’’ ‘‘Myths/facts,’’ ‘‘Climate science,’’ ‘‘Scientific references,’’ and ‘‘Contact us.’’ All of the content was based on information found on real-world grassroots and astroturf web-sites ….

A further manipulation consisted of disclosing information regarding the funding source that supported the organization. The organization’s name in all websites, regardless of the condition, was ‘‘Climate Clarity.’’ In each of the funding source conditions, all web pages within the condition specified who funds the organization (donations, Exxon Mobil or the Conservation Heritage Fund). The ‘‘no disclosure’’ condition did not have any information on funding sources anywhere within the web pages.

I trust readers of this blog can see why this study design is…relevant.

Interestingly, when the results were gathered, it turned out that information about the site’s funding source didn’t have any significant effect on the study participants’ views. However, readers of the astroturf sites were much more likely to feel that the science of global warming is uncertain, and to question the phenomenon’s human causation.

One finding was particularly disturbing: People found the Astroturf messages less trustworthy overall, and yet were still influenced by them. The most influenced were those study participants who were the least engaged in the climate issue–and thus, presumably, the most vulnerable to astroturf misinformation.

In many ways, this study bulwarks assumptions that I—and many of us—had already. The one surprising thing was that funding source didn’t seem to matter—but you have to wonder about this finding a little.

The study used “ExxonMobil” as the funding source for Astroturf groups, but what that actually signified to study participants is unclear. When funding sources of Astroturf groups are revealed in blogs and on the media, you generally get a lot more information than this–and a much greater tone of outrage. Perhaps a more realistic test of this condition would lead to a different result.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts