Considering the rate at which natural gas resources are being developed, and the sudden push from industry to export the product, it might come as a surprise that the Senate’s Energy Committee hadn’t had a hearing on liquified natural gas (LNG) since 2005.

Last Tuesday, for the first time in six years, Senators brought the issue back to the Capitol spotlight, as they considered the impact of exporting LNG on domestic prices.

In order to export or import natural gas, companies can either transport it through pipelines, or ship it as liquefied natural gas (LNG). LNG is natural gas cooled to -260 degrees Fahrenheit, at which point the gas becomes a liquid. Back in 2006, LNG imports far outstripped exports, and industry used that trade deficit to push for a massive expansion of domestic drilling, relying heavily on the argument for American “energy security.”

Now that that expansion is well-underway, with the infamous Utica and Marcellus shales the frontier of rapid development, utilizing controversial fracking and horizontal drilling techniques, the industry is eager to start exporting LNG to international markets where the fuel fetches a much heftier price.

The Senate hearing comes in the wake of a massive 20-year, $8 billion deal between the British BGGroup and Houston-based Cheniere Energy.

The amount of LNG represented in that deal alone amounts to roughly 3.3 percent of all current U.S. natural gas consumption.There are currently four other export applications on the desks of the Department of Energy (Dominion Energy’s Jordan Cove project, which I wrote about here, is another), and together they would be the equivalent of 10 percent of current U.S. natural gas use, according to Chris Smith, a Deputy Assistant Secretary of Oil & Gas at the DOE.

Exporting that amount of LNG alone is, lawmakers worry, enough to impact domestic prices. Earlier this year, when the DOE approved the export permit for the Sabine Pass LNG project in Louisaiana (where the Cheniere LNG would ship off towards Europe), the department admitted that the project would raise gas prices in the U.S. by more than 10 percent.

Speaking at the hearing last Tuesday, Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon put Smith on the spot as to the rational of that decision:

The agency must determine whether the export projects are in the “national interest” during the approval process.

These first five proposed export deals represent, as Reuters referred to the Cheniere deal, “a new chapter in the shale gas revolution that has redefined global markets.”

Many energy experts, environmentalists, and lawmakers like Senator Wyden are concerned that, despite the rhetoric, a massive expansion of natural gas drilling won’t actually improve America’s energy security or self-reliance, but will only help the gas companies reach more lucrative foreign markets, leaving Americans to clean up the mess and pay for any pollution, spills, or long-term ecosystem degradation, as well as paying higher natural gas prices.

As proof of the industry’s intention to tie into a global market, Wyden held up a graph of LNG prices worldwide, showing that prices are up to three times higher overseas than they are in the United States.

(DeSmogBlog has contacted Senator Wyden’s office for a clearer copy of that graph, and will post it when we receive it.)

Showing the graph, Wyden warned, “Exports in the United States are going to make natural gas like the oil market. That’s why I’m concerned about what these price hikes could mean for our businesses and our consumers.”

Some other interesting bits from Wyden’s testimony:

Also providing testimony was Jim Collins, director of underground utilities for the city of Hamilton, Ohio. Collins argued that exporting LNG would tie the country to international markets, and would increase domestic prices and cause Americans’ utility bills to rise. Collins is no anti-gas crusader. He supports the use of natural gas as a transportation fuel and electricity producer, but is worried that the export strategies of gas companies will leave Americans worse off.

Today, the vast majority of natural gas exports from the United States travel through pipelines into Mexico and Canada. Only about 5 percent of natural gas exports currently leave our borders as LNG from coastal ports. (I dug deeper into the natural gas trade numbers in this earlier post.)

As of last year, there were 11 LNG terminals in the United States, only one of which – Sabine Pass – is approved for exports. That the industry is lobbying so hard to open up other terminals for overseas shipping is proof that the “energy security” claims they’re making to rally favor around rapid shale gas development are disingenuous at best.

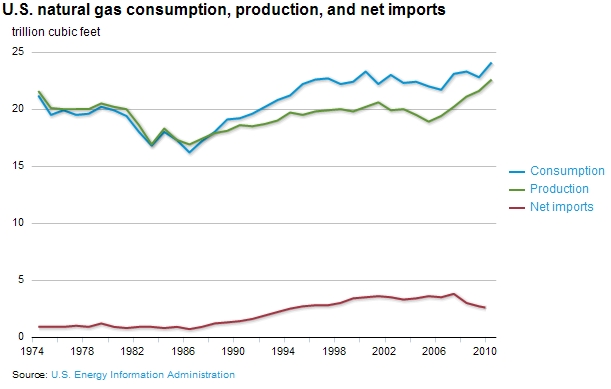

It’s worth noting that natural gas imports are still far greater than exports, and current natural gas demand still outstrips domestic supply. If “energy security” were the real goal, then the companies should be content closing the gap of domestic supply and demand.

But because the gas industry intends to tie into the more lucrative foreign markets as soon as possible, Americans will wind up paying higher energy bills, and will be left with all the risk, and cleaning up all the industry’s pollution and waste. Which is why so many energy experts, environmentalists and lawmakers see natural gas exports as a lose-lose for America.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts