This morning, investigators continue to search for missing Amtrak passengers, possibly thrown from a major train derailment and wreck in northeast Philadelphia Tuesday night. Already the casualty toll is one of the worst in recent memory, with at least seven people dead and over 200 injured after Amtrak’s Northeast Regional Train No. 188, carrying 258 passengers, derailed.

“I’ve never seen anything so devastating,” Philadelphia Fire Department Deputy Commissioner Jesse Wilson told NBC News yesterday.

For some of those living nearby, the Amtrak collision was also a grim reminder of another – even more dangerous – hazard on the rails.

“I feel lucky that wasn’t an oil train last night,” Joseph Godfrey, a retiree who lives two blocks from the crash site, told CNBC.

Between 45 and 80 oil trains – each a chain of tankers that can stretch over a mile long – roll through Philadelphia’s densely populated neighborhoods every week, mostly heading to a South Philadelphia refinery that is the nation’s biggest single consumer of the notoriously explosive crude oil from North Dakota’s Bakken shale. More than 400,000 Philadelphians, and an additional 300,000 in neighboring suburbs, live within a half-mile of tracks traveled by oil trains – and a half-mile represents the evacuation zone for an oil train derailment, according to federal regulators.

Alll told, over 25 million Americans nationwide live within a half-mile of oil train tracks, one 2014 analysis found.

Locals say that tanker cars carrying oil traverse the section of tracks where the Amtrak wreck occurred daily. The Amtrak train was travelling along the Northeast Corridor, where passenger trains often share the same rails as oil trains. At the site of the derailment, oil trains run on tracks parallel to Amtrak’s rails – and in fact, the Amtrak train may have come perilously close to striking oil tankers.

Photos from the time of the accident posted on Twitter appear to show the Amtrak train came within feet of tanker cars that were stopped on tracks parallel to the passenger rails.

“It missed that parked tanker by maybe 50 yards,” Scott Lauman, who lives near the wreck site, told CBS. “An Amtrak guy came by and he was telling me it turns out those tankers are full, and if that engine would’ve hit that tanker, it would’ve set off an explosion like no other.”

Robert Sumwalt, an official representing the National Transportation Safety Board, told reporters at a Wednesday press conference the agency was told the tankers were not completely full, but did not say whether that meant they carried no crude oil or whether they were only partially full. He added that he had not verified independently how full the cars were.

The issue drew the attention of the state’s top executive, as he visited the derailment site yesterday. Pennsylvania’s Governor Tom Wolf called the nearby tanker cars “a cause of additional concern.”

And oil train activists say that the Amtrak crash could potentially have been avoided if federal regulations requiring automated speed controls had gone into effect earlier – but instead, the federal government has allowed train companies to delay installing those controls.

Just one day after Tuesday’s wreck, the American Petroleum Institute filed a lawsuit challenging new federal safety standards for oil trains.

Although investigators are still combing through the wreckage looking for a full explanation of the cause of the wreck, speed seems to have been a major factor in the disaster. According to the National Transportation Safety Board, the Amtrak train that derailed was going 106 miles per hour, twice the speed limit, as it made its way around a curve that was the site of one of the deadliest railway accidents in U.S. history, a September 6, 1943 passenger train crash that killed 79 and injured 117.

The Amtrak train was equipped with Positive Train Control (PTC) equipment, that would use GPS data to automatically slow trains going over federal speed limits, but the section of track where the derailment occurred had not yet been upgraded to allow the PTC technology to work.

“A faster pace to implement federal rules requiring Positive Train Control systems on Class 1 tracks with commuter trains and high volumes of freight might have made the difference in this accident,” Matt Krogh, director of the Extreme Oil Campaign at ForestEthics, told DeSmog.

Already in Philadelphia, where a refinery surrounded by residential neighborhoods is the nation’s top destination for notoriously explosive Bakken crude, oil trains have derailed twice since January 2014. In one incident, cars filled with oil derailed on a bridge and dangled over the Schuylkill river and prompted the shutdown of a nearby expressway.

“The rapid rise of oil trains in Philadelphia and nationally parallels the rise in accidents and near misses,” Mr. Krogh told DeSmog.

“So far we’ve been lucky, but it’s just a matter of time until a major derailment happens in an urban center like Philadelphia.”

Flying Manhole Covers, Toxic Clouds

Suppose the Amtrak train that derailed had carried flammable material instead of passengers, and that flammable material ignited. An oil train explosion involves a series of escalating disasters, each posing unique dangers, particularly in urban environments.

According to the U.S. Department of Transportation, the potential impact zone of an oil train explosion includes a one mile radius around the blast site.

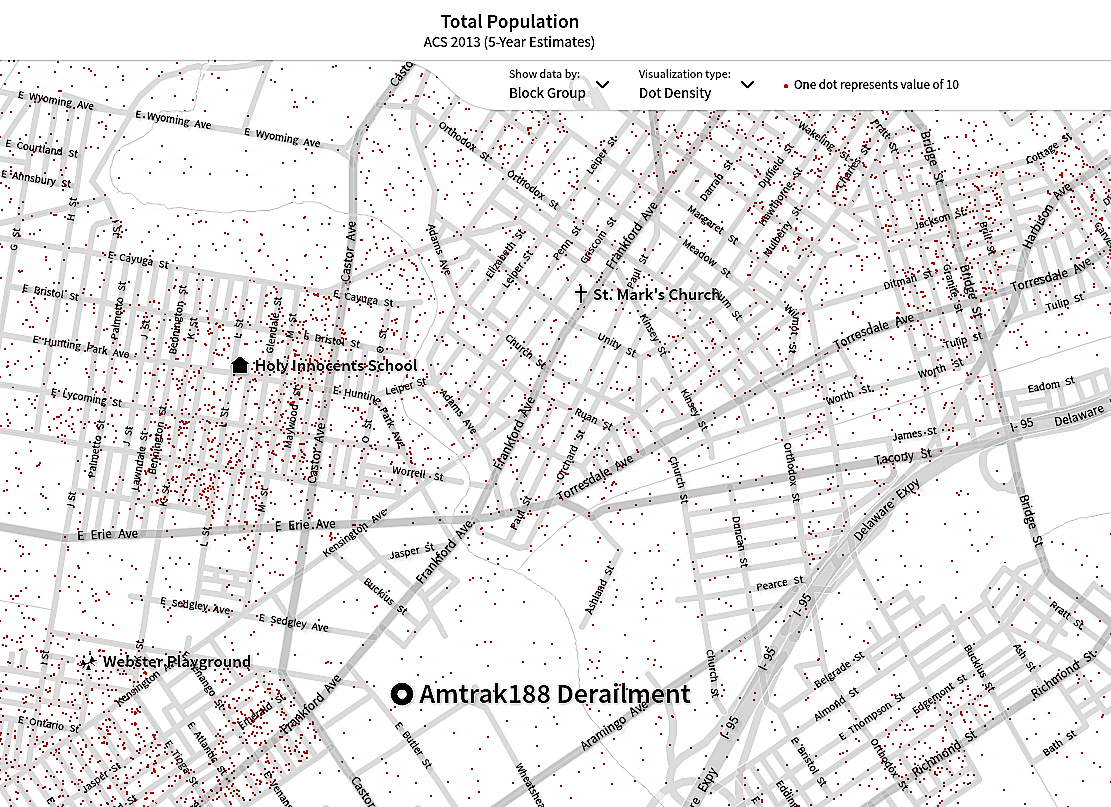

Around 47,000 people live within a one-mile radius of Amtrak 188’s derailment, according to five-year estimates from the 2013 American Communities Survey.

A few blocks to the northwest is Holy Innocents Area Catholic Elementary School, which reports an enrollment of 287. A few blocks further north and toward Frankford Ave. is St. Mark’s Episcopal Church.

Map Credit: Jack Grauer, Spirit News

“Let’s say there was [hazardous material] in those rail cars,” Jim Blaze, an economist and railroad consultant told NPR. “If the cars cracked open, it could have been an explosive force and caused a chain reaction. What would the casualty rate have been as a result? Could you imagine evacuating 750,000 people? What’s that going to cost? What’s the lost business revenue?”

The recent string of oil train derailments and fires – the Feb. 17 derailment in West Virginia , the March 9 derailment in Gogama, Ontario, the May 6 derailment in the 20-person town of Heimdal North Dakota – have occurred in rural areas, away not only from dense population centers but also from the infrastructure that undergirds cities and towns.

Because of the labyrinth of sewer systems and underground utility tunnels – not to mention other industrial sites – oil train explosions in a major US city would pose unique hazards. First responders would likely contend with a broad array of surprising dangers.

For example, in the 2013 oil train explosion in the Canadian town of Lac-Megantic, population 2,000, hazards were not limited to the fireball. Hundreds of thousands of gallons of Bakken crude oil – described not like the tar balls that washed onshore following the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, but as slightly less watery than vegetable oil – spilled through the streets and down into sewers.

Explosions from the fumes that built up in those tunnels blew manholes over 30 feet into the air, investigators found. Burning oil melted streetlamps, flowed into rivers and lakes, and soaked deep into the ground after it poured from the train.

Toxic clouds from the fumes also kept first responders at bay, limiting their ability to approach the wreck initially and then also keeping them from areas close to the crash site for days.

And then there’s the train car explosion itself – not only involving the burning of the 30,000 gallons of oil carried in each DOT-111 tanker car, but also what fire engineers call a BLEVE, standing for a Boiling Liquid Expanding Vapor Explosion. As liquids in a metal tank boil, gasses build up, pressurizing the tank even despite relief valves designed to vent fumes. Tanks finally explode, throwing shrapnel great distances, and spitting out burning liquids that can start secondary blazes.

In the Lac Megantic disaster, 30 buildings were leveled by the blast and subsequent fires, and officials said they believed some of the missing could have been vaporized in the explosions and fires. Hospital officials reported that emergency rooms were eerily empty following the blast. “You have to understand: there are no wounded,” one Red Cross volunteer told the local press at the time. “They’re all dead.”

In light of these hazards and many others – the risk of a domino-like series of subsequent disasters and spills if an explosion occurred in an industrial area – emergency planners often focus on evacuation.

Philadelphia’s emergency response plans in the event of a derailment and explosion have not been made public, local activist groups complain, prompting fears that the plans may not be sufficiently detailed.

‘No Traffic Cops’

Meanwhile, an increasing amount of oil is moving by train through one of America’s largest cities, as Philadelphia Energy Solutions purchased an old Sunoco refinery – first established in 1866, long before regulations made it nearly impossible to build new refineries in urban centers – and added the East Coast’s largest railcar unloading facility.

“We’re now the single largest buyer of crude from the Bakken in North Dakota,” Philip Rinaldi, the refinery’s chief executive, told a Drexel University conference last December. “We bring in nearly six miles of train a day for unloading at our facility.”

Unlike passenger trains, heavy axel trains like oil trains can cause rails to flex ever so slightly – prompting concerns that rails used by both oil trains and passenger trails could be at greater risk of broken welds or rails.

And damaged welds and rails are the number one cause of train derailments nationwide, Federal Railroad Administration data shows, responsible for rought 40 percent of overall derailments. This means that the sharp increase in oil train traffic could make it more likely that passenger trains using the same rails could crash.

Oil trains travel on parallel rails on the section of track where Amtrak 188 crashed – but over Amtrak’s entire Northeast Corridor, the nation’s most heavily traveled passenger railways, oil trains at times travel on the same rails as passenger trains.

With risks like these in mind, Philadelphia’s railroad unions called for tougher rules in April.

“The industry arrogantly claims they cannot afford to maintain the tracks to a higher safety standard,” Freddie N. Simpson, president of the Maintenance of Way Brotherhood, which represents workers who inspect and maintain railroads, told the Philadelphia Inquirer. “My question to the nation is, Can we afford for them not to?”

Trains are generally required to run at slower speeds on tracks that are less frequently inspected.

But oil train activists point out that speed limit enforcement is left up to railroad companies themselves, meaning that there is no available data on how often trains exceed speed limits.

“There’s no tracking or recording,” Mr. Krogh told DeSmog, “there are no traffic cops on the rails.”

Public officials say that efforts to regulate oil trains locally to prevent explosions are hamstrung by the fact that train regulation up to the federal government. Philadelphia City Council passed a resolution in March urging the federal government to enact new rules – but can do little otherwise, local politicians say.

“It is very frustrating, because on a local level we have very limited powers to regulate the railways,”City Councilman Kenyatta Johnson told the Philadelphia Inquirer in February. “The federal government needs to step up. The Department of Transportation needs to do more to hold these railroads more accountable.”

Photo Credit: Joshua Albert, Spirit News

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts