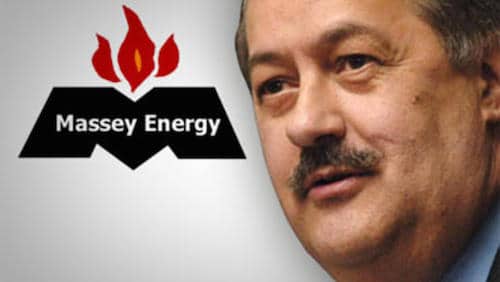

As jury selection begins for the trial of coal baron Don Blankenship, his team of lawyers are doing everything possible to prevent prosecuting attorneys from mentioning the Upper Big Branch mine explosion that claimed the lives of 29 mine workers.

Blankenship is currently awaiting trial on charges of conspiring to violate mine safety standards and making false statements. These charges are what ultimately led to the mine disaster, but Blankenship has not been charged for that explosion.

Blankenship’s lawyers have filed a motion to prevent prosecutors from presenting any evidence regarding the Upper Big Branch explosion during the trial and jury selection process.

The reason they want this information excluded from the trial is because this explosion rocked the community in which Blankenship is due to stand trial, and it will be difficult to find jurors who don’t have extensive knowledge — or perhaps even personal connections — to the disaster.

Should U.S. District Judge Irene Berger agree with the motion, it will not necessarily be a slam dunk for Blankenship’s legal team. After all, the indictments are not related to the explosion, so the evidence against Blankenship will still stand.

And that’s where the lawyers are going to run into even more problems.

As Sharon Kelly laid out on DeSmog in 2013:

For the past two years, the U.S. Attorney in West Virginia, R. Booth Goodwin II, has been systematically working his way up Massey’s hierarchy, arguing that beyond the managers who supervised that mine, there was a broader conspiracy led by still unnamed “directors, officers, and agents.” Goodwin has based his prosecutions on conspiracy charges rather than on violations of specific health and safety regulations, which means he can reach further up into the corporate structure. So far, he has convicted four employees including the Upper Big Branch mine superintendent who admitted he disabled a methane monitor and falsified mine records.

But in February (2013), the case took a surprising turn. In pleading guilty to conspiracy charges, Dave Hughart, former President of a Massey subsidiary who is cooperating with the government, said that the person who had alerted him to impending mine inspections was Massey’s CEO, Don Blankenship – an accusation that sent a gasp through the entire coal industry.

Kelly also points out that Massey field offices were operating under the rule “Do As Don Says,” implying that Don Blankenship himself was calling the shots when the company cut corners on safety procedures and conspired to keep this information hidden from state and federal regulators.

Judge Berger, who will preside over the case, had previously instituted a gag order on both parties involved in spite of the fact that neither the prosecution nor the defense requested such an order. This order was lifted by a Federal Appeals Court earlier this year.

It is likely that Judge Berger will indeed grant the motion to bar evidence related to the mine explosion, but that shouldn’t hinder the case for the prosecution. If the witnesses are still willing to testify about Blankenship’s personal involvement in the cover ups, then this should be an easy win for the prosecution.

If convicted, Blankenship could face up to 31 years in prison.

Image via CBS News.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts