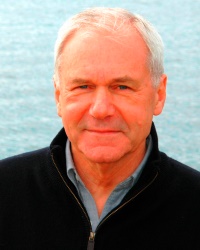

Scientist Dr Graeme Pearman knows more than most about the responsibilities and the perils that come with communicating climate change to the highest authorities.

As one of Australia’s highest ranking government scientists, he was asked into the offices of three consecutive Australian Prime Ministers to brief them on climate change.

In the late 1980s, it was Labor Prime Minister Bob Hawke. Then in the 1990s, it was Hawke’s Labor successor Paul Keating. As the decade wore on, it was the conservative Liberal Prime Minister John Howard on the other side of the briefing table.

Pearman was a senior scientist in the Atmospheric Research division of the CSIRO – the nation’s top government science and research organisation.

As well as liaising with political heavyweights, Pearman gave hundreds of briefings to other agencies and organisations in the public and private sector.

My profile I think grew from a broad view of both the climate science but also the potential consequences. I also held strong views that as a public servant I had a responsibility to publicise scientific findings of wider potential relevance.

My relatively senior role in CSIRO – which ultimately was my downfall – provided me with a platform perhaps less available to others.

Pearman is no longer at the CSIRO. He ended his 33-year stint with the agency in 2004 — resigning after a period when, he has said, he was being internally censored over his views on climate change.

So what would he tell the current Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, if he ever were asked into that particular Canberra office (he hasn’t been, so far).

My suggestions would be, listen to real experts, scientists, economists and engineers, and Academies about options; listen to the real trend occurring overseas in particularly with respect to energy sourcing and application options; look beyond the term of the current Government and think strategically; see this as an opportunity rather than a negative.

Earlier this month the Abbott Government announced the greenhouse gas reduction target it would take to the major United Nations COP21 climate talks in Paris in December. The target to cut emissions between 26 and 28 per cent by 2030 from 2005 levels has been roundly criticised for lacking ambition.

Pearman, who has continued his work as a scientist and consultant, says the government should have taken the advice of the Climate Change Authority, a statutory body set up to provide advice on policies to cut greenhouse gases.

The CCA, which the government has said it wants to scrap, has recommended Australia cut greenhouse gas emissions by between 45 and 63 per cent by 2030, if the same 2005 baseline year was used.

Pearman, pictured, told me the government’s decision to ignore the CCA’s advice was an example of a “culture trend” that had emerged over recent years that had seen “a decreasing dependence on expert advice in favour of preferred advice”.

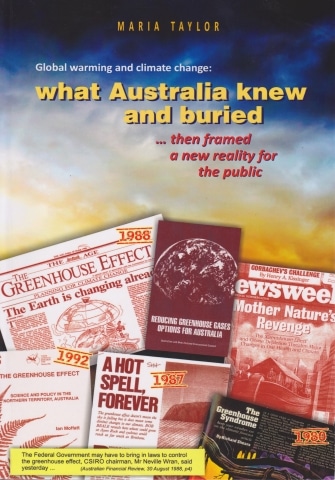

Pearman’s time within CSIRO overlaps entirely with the period studied by journalist Maria Taylor in her new book Global Warming and Climate Change: What Australia Knew and Buried … Then Framed a New Reality for the Public.

The veteran scientist was one of the dozen or so insiders interviewed for the book, which tells the story of how Australia was set to act on greenhouse gas emissions 25 years ago before momentum was halted by a combination of vested interests and a fundamental shift in political ideology.

In 1990, Prime Minister Hawke wanted a policy that would see Australia cut its emissions by 20 per cent by the year 2005. Taylor’s book explains how this was a time when the government accepted the evidence that humans were the chief cause of global warming and that action needed to be taken.

Much of Australia’s media accepted the evidence too, as did the relevant public agencies, state governments and much of the public. In a review of the book, Pearman writes:

Maria Taylor’s book carefully unravels the developments that took place that now leave Australia in danger of international sanctions because of its pariah status, to say nothing of the impacts of climate change itself.

Today, because of this change of culture, there is a much greater polarization of attitudes towards the climate change issue, and a much greater reluctance to accept independent advice in policy development if it does not support ideological directions. This makes the role of the expert in contributing to policy development more difficult but, in many ways, more important than ever.

Taylor’s book looks at how so called “free market” think tanks worked in tandem with the fossil fuel industries to reshape climate change and global warming in the eyes of the Australian public.

“It all went wrong with the impost of neoliberal economics starting with Paul Keating,” Pearman tells me.

As the book recounts, under Keating a false dichotomy was put before the Australian people — that you couldn’t have action on environmental issues and have a strong economy.

Policy makers started to shift away from regulating industries after being convinced by lobbyists and neoliberals that having a so-called “free market” was more important.

Or in a more succinct description of the events that unfolded, mostly out of public sight, author Taylor has concluded: “We have been propagandised.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts