By Sarah Perkins-Kirkpatrick, UNSW AustraliaAndrew King, University of Melbourne, and Geert Jan van Oldenborgh

On May 19, India’s all-time temperature record was smashed in the northern city of Phalodi in the state of Rajasthan. Temperatures soared to 51℃, beating the previous record set in 1956 by 0.4℃.

India is known for its unbearable conditions at this time of year, just before the monsoon takes hold. Temperatures in the high 30s are routine, with local authorities declaring heatwave conditions only once thermometers reach a stifling 45℃. But the record comes on the back of an exceptionally hot season, with several heatwaves earlier in the year. So what’s to blame for these scorching conditions?

Much of India is in the grip of a massive drought. Water resources are scarce across the country. Dry conditions exacerbate extreme temperatures because the heat energy usually taken up by evaporation heats the air instead.

The complex relationship between droughts and heatwaves is an area of active scientific research, although we know a preceding drought can significantly amplify the intensity and duration of heatwaves.

India’s drought was a possible factor in the earlier heatwaves in April over central and southern India. However, Rajasthan, where 51℃ was recorded, is always bone-dry in May. So the drought made no difference to the record temperature.

The El Niño effect

We have also experienced one of the strongest El Niño events on record. While the current event has recently ceased, its sting is certainly still being felt.

El Niño episodes are associated with higher-than-average global temperatures and have also been a factor in some of India’s past heatwaves. However, there is no direct connection to El Niño in Rajasthan, because its climate at this time of year is so dry anyway.

India also has an extreme air pollution problem. Caused largely by domestic fuel and wood burning, it kills up to 400,000 people every year. This pollution, made up of fine particles called aerosols, also has the effect of cooling the local climate by reflecting or absorbing sunlight before it reaches the ground, thus reducing the likelihood of the most extreme high temperatures.

So although India is no stranger to extreme heat at this time of year, the smog has kept record-breaking high temperatures at bay – until now. This is what makes the record in Phalodi remarkable.

Longer-term heat extremes

A study published in 2013 analysed annual trends in extremes and found no significant change in the intensity of extreme Indian temperatures between 1951 and 2010. The high levels of local air pollution were probably behind the lack of change.

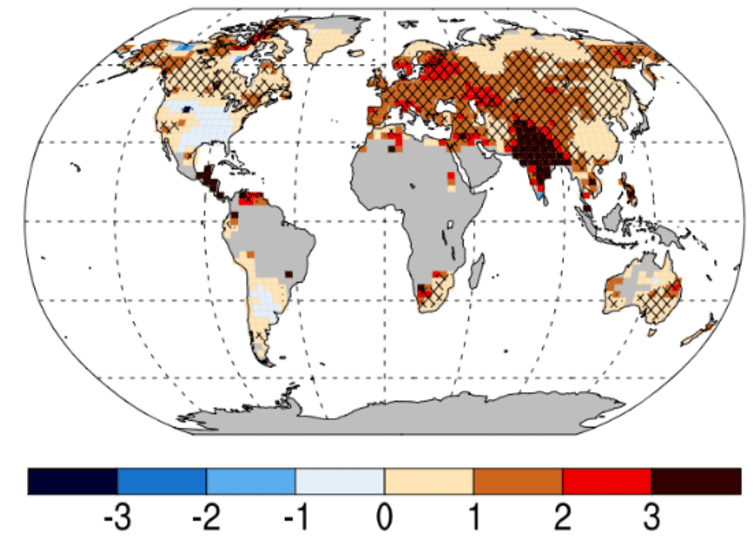

However, the study found a significant increase in the frequency of extreme temperatures and a remarkable trend in the duration of warm spells in India, as the map below shows. Warm spells, defined as at least six days of extreme temperatures relative to the location and time of year, increased by at least three days per decade over 1951-2010 – the largest trend recorded globally.

It is worth keeping in mind that these trends are annual and are influenced by extremes all year round. However, monthly trends in the frequency of Indian temperature extremes for May, which can be found on the CLIMDEX climate database, show an increase over the past 60 years.

Based on local station data, the Indian Meteorological Department reported that many northern states experienced an average of eight heatwave days each March-July between 1961-2010. Trends in “normal” and “severe” heatwaves increased over this time, and in particular over the last decade of the analysis.

Some Indian regions also tended towards longer and more intense heatwaves after an El Niño, and northwestern states of India, where Phalodi is located, tend to experience more intense events anyway. Trends in the intensity of extreme temperatures are less clear and vary across the country.

Different spatial and temporal scales and methods of quantifying extreme temperature hamper a direct comparison of the two studies described above. However, they both document an increase in the frequency of extreme temperatures over India, which is consistent with many other regions worldwide. Heatwave indices and the hottest yearly temperature have only increased significantly in a relatively small region of western India.

What will the future bring?

Most climate models do not do a great job of capturing observed trends in heatwaves over India, because large-scale models struggle to accurately represent the localised effect of aerosols.

It is therefore difficult to use them in great detail for future projections, particularly if pollution levels continue or even increase. However, if air pollution is reduced, temperatures will rise with a vengeance. We know this from experience over Europe, where summer temperature trends were virtually zero up to the 1980s and very strong afterwards, once air pollution was controlled.

Even though this is the hottest time of the year for the region, the recent weather should not be dismissed as regular. It is feasible that India’s pollution problem has been “hiding” extreme heat spikes.

While any clean-up activities will have many positive local health impacts, these are likely to cause more intense heatwaves in future. This will be amplified by background warming due to climate change, which is also likely to drive increases in the frequency of temperature extremes.

Last year India and neighbouring Pakistan suffered similarly atrocious conditions, killing thousands of people. This year’s death toll is already in the hundreds, with numbers sure to rise further.

India is already highly vulnerable to the health impacts of oppressive heatwaves and, as climate change continues, this vulnerability will grow. It is therefore imperative that heat plans are put in place to protect the population. That’s a difficult prospect in places that lack communications infrastructure or widespread access to air conditioning.

In the longer term, this episode shows that the global warming targets agreed in Paris have to be taken seriously, so that unprecedented heatwaves and their deadly impacts don’t become unmanageable in this part of the world.

Sarah Perkins-Kirkpatrick, Research Fellow, UNSW AustraliaAndrew King, Climate Extremes Research Fellow, University of Melbourne, and Geert Jan van Oldenborgh, Climate researcher, Royal Dutch Meteorological Institute. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Main image: A man refreshes on a Calcutta Street in 2005. Credit Jorge Ryan, Creative Commons.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts