Just one month after the United States and China, two major greenhouse gas emitters, committed to the Paris climate agreement, the European Union has promised to follow suit and ratify the agreement, which aims to limit global temperature rise to “well below 2°C” and strive for 1.5°C.

Meanwhile, although the United States is notorious for partisanship over climate change, two Congressional representatives — one Republican and one Democrat — have just introduced a bill to create a bipartisan commission for climate solutions.

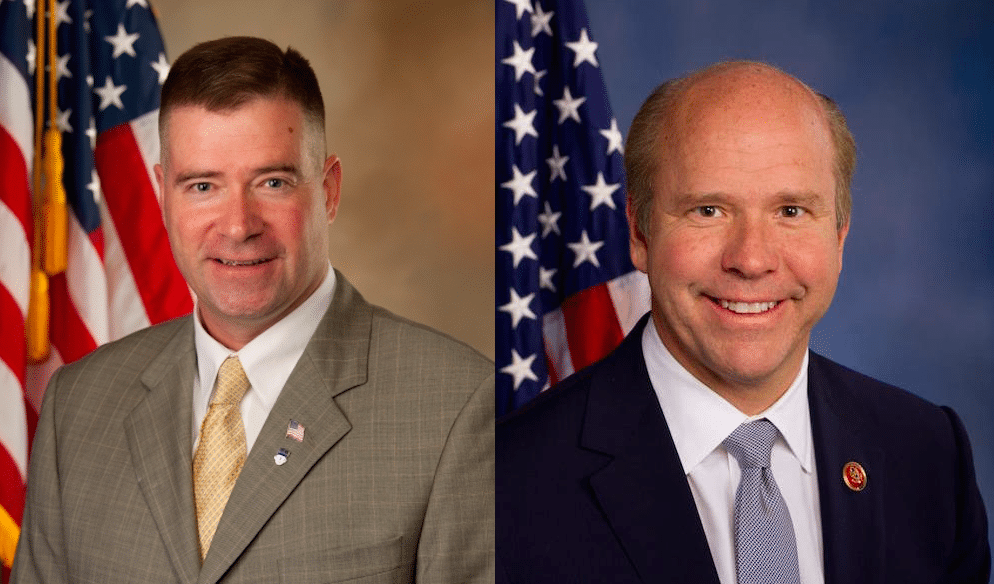

Led by Representatives John Delaney (D-MD) and Chris Gibson (R-NY), the Delaney-Gibson Climate Solutions Commission Act (H.R. 6240) would bring together the two political parties to create a 10-member commission to find agreement and create action on this historically divisive issue.

“Ultimately, the best path to a solution is to build bipartisan consensus — that process starts today with the introduction of this bill,” Rep. Delaney said in a statement released September 30. “I want to thank my colleagues in both parties for their courage in stepping forward on this issue.”

According to a statement from Rep. Delaney, the commission created by this bill will have three tasks:

- “undertake a comprehensive review of economically viable public and private actions or policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions

- make recommendations to the President, Congress and the States

- use as its goals for emissions reductions the estimated rates of reduction that reflect the latest scientific findings of what is needed to avoid serious health and environmental consequences.”

With half of its members appointed by each political party, the commission would be composed of scientific, nongovernmental, and private sector experts on climate and energy.

Nongovernmental organizations such as the World Resources Institute have applauded the bill’s origins and its focus on producing concrete solutions.

“I think it’s a very encouraging sign because it’s bipartisan,” said Christina DeConcini, government affairs director with the World Resources Institute. “I don’t think there’s been any bipartisan climate bill since 2009,” referring to the failed Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade bill which passed in the House but never made it out of the Senate.

She also called out the fact that this bill moves beyond Rep. Gibson’s 2015 Republican-sponsored resolution in the House, which focused on better stewardship of the environment, including the climate.

Joining Reps. Delaney and Gibson in support of the bill are Representatives Robert Dold (R-IL), Alan Lowenthal (D-CA), Theodore Deutch (D-FL), Scott Peters (D-CA), and Carlos Curbelo (R-FL).

Small But Growing Signs of Republican Leadership on Climate

A Republican freshman in Congress, Rep. Curbelo represents the district that includes Miami, which is already seeing the effects of rising sea levels. He has spoken out previously about both the reality of climate change and the need for bipartisan solutions.

As the Miami New Times reported in 2015, Curbelo has called climate change “a major challenge and threat we all face, especially in South Florida,” and has promised to “put party politics aside and seek bipartisan solutions to climate change and sea level rise.”

Making good on that pledge, he and Rep. Deutch, a Democrat also from South Florida, in February launched the Bipartisan Climate Solutions Caucus, a House bipartisan task force focused on climate change. This caucus produced the proposed Climate Solutions Commission bill.

While it was not the first climate task force in the House, the only other one, the Congressional Safe Climate Caucus, boasted 50 Democrats as members but not a single Republican, reported Bloomberg.

In a March op-ed in The Hill, Curbelo and Deutch acknowledged the environment they were operating in and the challenge before them in launching this bipartisan caucus:

“We know that the rigid partisan climate in the House and Senate has prevented Congress from tackling an array of issues in recent years. But the idea that the elected representatives of the American people cannot come together to even discuss climate change while the governments of nearly 200 countries can, as we recently saw in Paris last year, demonstrates the frustration of this stalemate … We cannot let partisan politics relegate the legislative branch of the United States to the sidelines as communities, local governments, and private industry grapples with an increasingly existential threat.”

Even as dozens of nations have ratified the Paris agreement, their commitments for reducing emissions do not add up to the goals set forth in the agreement, making additional reductions necessary in the future.

The U.S. has committed to cutting its greenhouse gas emissions 26 to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. Based on analyses by the World Resources Institute and others, the nation is capable of achieving this through existing laws and state action, with action being the key word.

While the EPA’s Clean Power Plan, which would require states to create plans to reduce carbon emissions from the power sector, is stalled in the courts, the past year increasingly has seen discussions on climate change cross the aisle in the House of Representatives.

However, with time running out in the current legislative session, the current Delaney-Gibson bill will likely not reach the floor. Still, observers see it as a much-needed sign of progress.

“We’re optimistic that this is one of several steps leading toward comprehensive, bipartisan legislation to address climate change in the next Congress,” Mark Reynolds, executive director of Citizens’ Climate Lobby, told DeSmog.

DeConcini agreed, pointing out that “it’s helpful in terms of signaling that we are going to need far greater ambition” after meeting the U.S. commitment to the Paris agreement. “We’re going to need a lot more of this type of support” to actually reach the agreed-upon goals for limiting warming, she told DeSmog.

Ratification Ups Importance of COP22 in Morocco

Despite its own challenges, the Paris climate agreement continues to gain momentum on the international stage.

On October 2, India became the 62nd nation to ratify the Paris agreement, bringing the combined global greenhouse gas emissions of committed nations to 51.89 percent. That is just shy of the required 55 percent for the agreement to enter into force.

With the European Parliament expected to sign off on the deal October 4, the European Union’s addition will likely push the agreement past the emissions threshold needed for it to take effect.

Should the Paris agreement be triggered this week, it will enter into force 30 days after ratification by at least 55 nations representing at least 55 percent of global emissions.

At that point, eyes will turn to COP22, the Paris follow-up summit in Marrakesh, Morocco, in November. That climate convention would then become the first official meeting of the parties to the Paris agreement.

There, nations would dig deeper into preparations for the agreement’s implementation.

“It is just nine months since we adopted the Paris Agreement and less than 6 months since we signed it,” said EU Climate Action and Energy Commissioner Miguel Arias Cañete at a press conference. “But this short period showed that Paris is a real game changer in global climate politics. Our partners are coming on board faster than anyone would have imagined. And Europe must show we can deliver too.”

Whether the world’s nations — and the U.S. Congress — will actually deliver on the Paris climate goals, however, remains unclear.

Main image: Rep. Chris Gibson, left, and Rep. John Delaney, right. Credit: Public domain.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts