Fracking companies are donating hundreds of thousands of pounds to a select group of UK MPs and Lords, parliamentary data reveals.

The contributions give the shale gas industry privileged access to lawmakers, and allows companies to promote their interests inside parliament.

Companies directly involved in the shale gas industry donated around £130,000 in funds or benefits in kind to the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Unconventional Oil and Gas in 2016, registry data shows.

Many of these companies are currently in the early stages of exploring for shale gas in the UK. Others are large US and multinational companies heavily involved in America’s fracking boom, which may be eyeing up UK investment opportunities if the conditions are right.

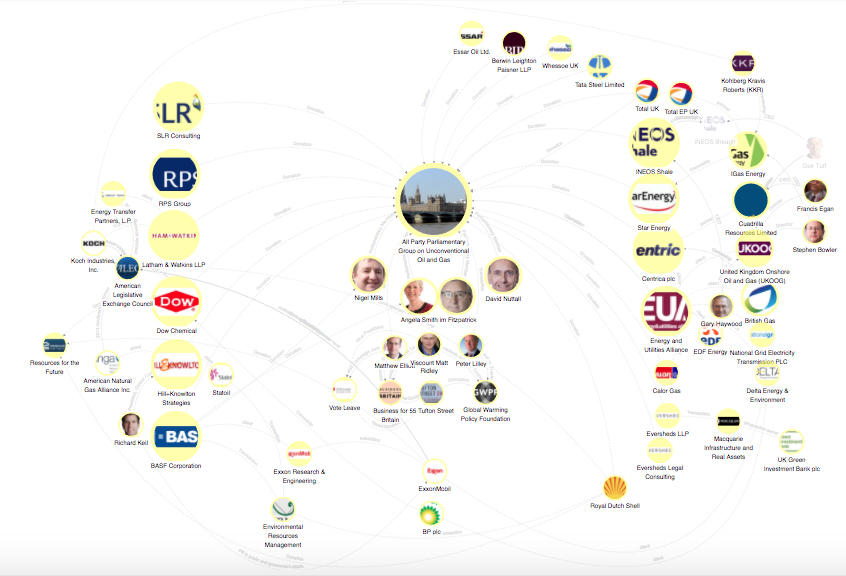

DeSmog UK has mapped the key connections between donors to the APPG, and Britain and America’s corporate fracking interests.

Fracking Network

All-party parliamentary groups were created to connect lawmakers with lobbyists and experts on particular issues. There are currently about 600 such groups. That’s up from 555 groups a year ago.

Labour MP Graham Allen described the groups’ funding as the “the next big scandal waiting to happen” back in 2014. But they still operate largely under the radar.

According to its website, the APPG on Unconventional Oil and Gas, “brings together politicians and policymakers with business groups, academics, NGOs and consumer groups to debate and explore the potential for developing unconventional oil and gas reserves in the UK in a rational manner based on the best evidence available.”

It runs regular events on all issues related to shale gas, bringing in high-profile speakers from politics and industry to rub shoulders with lobbyists and corporate representatives.

The APPG has four MPs acting as officers for the group. Each of them can be found repeating key industry arguments on the House of Commons’ floor.

For example, Labour MP Jim Fitzpatrick, one of the group’s vice-chairs, is fond of national security arguments for shale gas. Last May he told parliament that, “Shale extraction makes much more sense for our economic security [than importing gas], but the Government have to address the conflict between local communities being panicked and scaremongered into opposing shale extraction applications and the need for that national industry to be developed”.

Another vice-chair, Labour MP Angela Smith, has cited reports from trade body UK Onshore Oil and Gas’ (UKOOG) promoting the benefits of shale gas for the manufacturing industry in House of Commons debates, and has called on the government to “get things right by working with industry and by supporting the building of a business case for developing shale gas”.

Conservative MP David Nuttall, the group’s final vice-chair, has asked a number of pointed questions in the House of Commons on the issue. Last March, he asked then-Energy minister Andrea Leadsom if she thought “more can be done to extol the positive virtues of shale gas, including, for example, the new jobs and security of energy supply it will bring?”

All those arguments will be familiar to industry watchers.

Francis Egan, CEO of the first fracking company to start operating in the UK and another APPG donor, Cuadrilla, has claimed it could create “200 to 400 jobs” in the early stages of its activities.

Ken Cronin, CEO of UKOOG, the trade body that represents many of the APPG’s British donors, has regularly argued that importing gas rather than fracking puts the UK “at the mercy of not only volatile global energy markets, but both physical and political energy security issues”.

And Gary Haywood, CEO of APPG-donor INEOS, the UK’s largest shale gas player, is quick to promote the idea that shale gas is “about securing our manufacturing base which provides thousands of jobs in regional economies”.

Many experts say those benefits are reliant on optimistic assumptions. Academics from the UK Energy Research Centre have previously warned that politicians had “oversold” the benefits of fracking in the UK.

Given the donors to the group, and their regular attendance at the APPG’s events, it’s perhaps unsurprising their arguments make it onto parliament’s debating floor.

UK Donors

Companies with commercial assets in Britain and a strong interest in the UK’s nascent shale gas industry gave around £43,000 to the APPG in 2016.

The next 12 months could be critical for these companies, with operations finally due start at a number of key sites across the UK after years of protracted negotiations and litigation with local governments and campaigners.

Through a web of ownership, association memberships, and directorships, most of the UK’s key shale gas players along with many familiar big oil names have access to the parliamentary group.

Centrica / Cuadrilla Resources

Centrica is a partner of Cuadrilla Resources, perhaps the most symbolically important company in the UK’s shale gas industry. Centrica donated £2,500 to the APPG in 2016.

Centrica has a 25 percent stake in one of Cuadrilla’s fracking fields in Lancashire. In October, communities secretary Sajid Javid overturned local government opposition to Cuadrilla’s plans to frack in Lancashire. Cuadrilla started work on the site in early 2017.

Star Energy

Star Energy holds licenses to frack around Chester. It donated £2,500 to the APPG in 2016.

It is owned by IGas, a company backed by French oil giant Total. It holds licenses to explore for oil and gas in the UK in its own right, as well as owning other fracking companies such as Dart Energy.

Late last year, IGas was subject to a hostile takeover bid from US private equity firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR). KKR part owns an oil pipeline in Alabama with Koch Industries, owned by two of the world’s largest known funders of climate science denial, the Koch Brothers.

INEOS

INEOS has also donated £2,500. Mainly a chemicals company, it is looking to diversify its business and become a “major player” in the UK’s shale gas industry.

It holds licenses to frack in over a million acres in Cheshire, the midlands and Yorkshire. The first shipments of US shale gas to reach the UK’s shores were delivered to an INEOS plant in Scotland last year.

Energy and Utilities Alliance

Trade association the Energy and Utilities Alliance (EUA) gave £5,000 to the APPG in 2016, making it the group’s largest non-corporate donor.

The EUA represents groups including British Gas, which is also owned by Centrica, and UKOOG, the main lobby group for oil and gas in the UK. Cuadrilla CEO Francis Egan, IGas CEO Stephen Bowler, and INEOS CEO Gary Haywood are all UKOOG directors.

EUA also represents consultancy Delta Energy and Environment, which lists big oil companies such as ExxonMobil, BP, Statoil, and ConocoPhillips as clients. Delta Energy and Environment tells DeSmog UK it does not consult on fracking, and has no expertise, capability or interest in the issue.

EUA told DeSmog UK it contributes to the APPG to help pay for a newsletter, and to engage with policymakers to ensure the decarbonisation of the UK’s has supply is done “in a manner that is affordable for the UK consumer”.

A spokesperson for EUA said:

“We do not represent those companies engaged in hydraulic fracturing shale and we receive no income from them. For us, the challenge is to achieve our international climate change obligations, affordably whilst ensuring even the most vulnerable in society can access heating in their homes and workplaces”.

Royal Dutch Shell and Total

Two big oil companies made donations in their own names: Shell and Total.

Total actually made two £2,500 donations: one from its UK arm and one from its North Sea operations arm (Total E&P). Total holds 40 percent shares in two East Midlands shale gas sites.

Shell has major North Sea oil and gas assets, including the Brent oilfield that is used to set international benchmark prices. Shell has previously said it won’t look into fracking in the UK until another company has made a success of the industry. It does, however, have major fracking assets in the US, Canada, and Argentina.

US Donors

The fracking industry’s influence doesn’t stop at Britain’s borders. Most of the APPG’s funding actually comes from companies with a strong presence in the US, which donated over £80,000 to the group in 2016 – almost double that donated by British and European companies.

Over the past decade the US has gone through a shale gas boom, and fracking supporters have long argued that the UK could follow suit if the regulations were right.

The APPG even held a recent event on the issue, with a presentation from an INEOS consultant geologist.

The donations suggest US companies are looking for opportunities to influence UK policymakers, and have at least one point of access to those with responsibility for regulating the burgeoning industry.

Many of the donors have strong links with some of the biggest names in the global oil and gas industry.

Hill and Knowlton

The APPG’s biggest donor is PR company Hill and Knowlton Strategies (H&K), which donated £73,501 in services in kind in 2016 through performing the group’s ‘secretariat’ function.

H&K is perhaps best known for representing ExxonMobil during the Exxon-Valdez oil spill crisis in Alaska in 1989. It also represented the tobacco industry.

It has form when it comes to pushing the interests of the oil and gas industry in the US. It represents America’s Natural Gas Alliance, and set up a tar sands oil astroturf group in Alberta, Canada. Statoil is also a client.

Latham and Watkins

Another big US company to donate to the APPG is law firm Latham & Watkins, which donated £2,500.

It has represented both Koch Industries and Energy Transfer Partners, which owns the infamous Dakota Access Pipeline that Donald Trump revived with one of his first executive orders as president.

Exxon Connection

While ExxonMobil didn’t donate to the APPG itself, many donors have ties to it. Exxon this week doubled its fracking assets in Texas, but is yet to enter the UK shale gas market.

H&K recently hired Exxon oil and gas PR man Richard Klein as an executive vice president. Exxon is also connected to Dow Chemical, which donated £2,500 to the APPG, through groups known to propagate climate science denial including the American Legislative Exchange Council. Oil giant BP also has a 16 percent ownership stake in Dow Chemical.

BASF

Chemical giant BASF donated £2,500 to the APPG in 2016. It lists clients including Exxon and Russian state company Gazprom.

Not only did BASF donate to the APPG, but it also paid for two of its parliamentary members to go on foreign visits. In July 2016, Labour MP Angela Smith, visited BASF’s chemical complex in Ludwigshafen, Germany. In 2013, it paid for the group’s chair, Nigel Mills, to do the same visit.

Climate Deniers

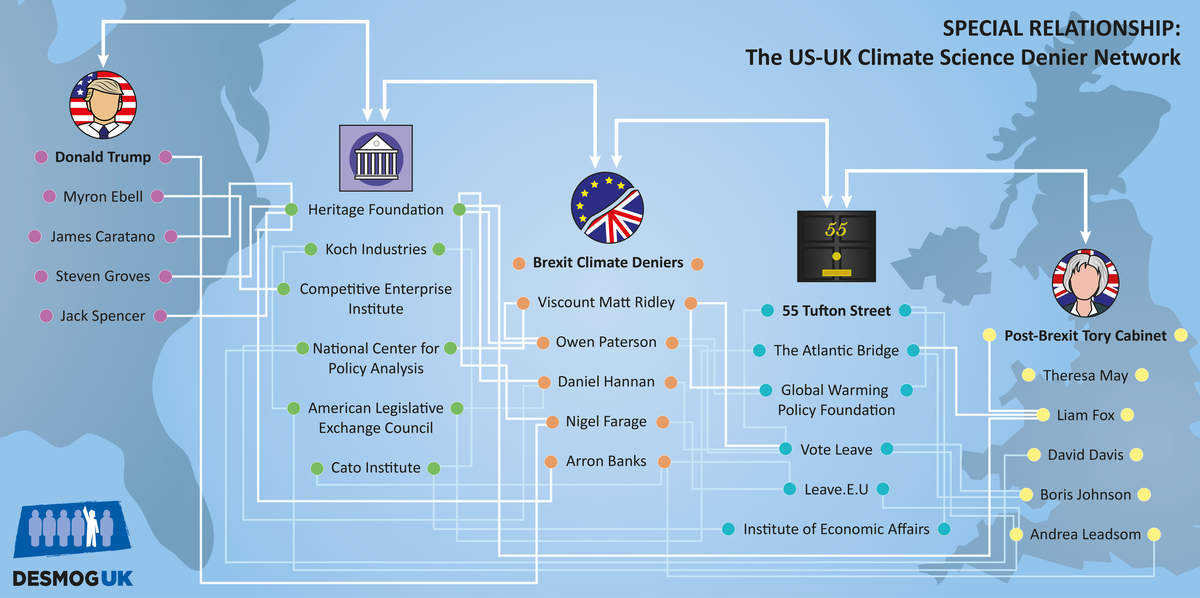

Given the cross-Atlantic corporate interests, and the potential damage to the climate that could occur as the UK’s shale gas industry develops, it is unsurprising to find an element linked to the Brexit-Trump climate denier network operating around the fringes of the group.

The APPG invited Matthew Elliott, chief executive of Vote Leave campaign and director of Business for Britain, to speak at an event on how small businesses could “make onshore oil and gas a British affair”.

Business for Britain was based in 55 Tufton Street, which acted as a hub for the UK’s brexiteer climate science deniers.

Conservative MP Peter Lilley also attended the APPG’s AGM in 2016. Lilley sits on the board of the climate science denying Global Warming Policy Foundation (GWPF). The GWPF are also based at 55 Tufton Street.

Lilley did not respond to a request from DeSmog UK to clarify his relationship with the APPG.

Close Friends

There remain many questions over why an APPG needs almost £130,000 of donations and benefits in kind to operate.

A spokesperson for Angela Smith told DeSmog UK the money was “for visits, events etc”, and suggested contacting H&K Strategies in its role as secretariat.

H&K did not provide any further details when contacted by DeSmog UK. The APPG’s chair, Conservative MP Nigel Mills, did not respond when asked for clarification of how the funds were spent.

All the MPs involved in the group maintained that the APPG was an open forum for discussions related to the UK’s shale gas policy.

David Nuttall told DeSmog UK that the APPG “is open to all both those who support and those who oppose fracking”. Angela Smith and Jim Fitzpatrick said discussions within the APPG did not influence their views on fracking. Nigel Mills did not respond to DeSmog UK’s request for comment.

Explore the donations in this google spreadsheet

Updated 20/02/2017: A line was added clarifying Delta Energy and Environment’s relationship with the companies listed.

Main image credit: DeSmog UK CC BY–SA

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts