On March 8, a train pulling 80 tank cars of ethanol derailed in Providence, Rhode Island. Luckily, no ethanol was spilled and no one was injured. However, activists immediately began calling for a halt to these “unit trains” of ethanol into and out of the city, noting the potential risks to the community. Unit trains are longer than average freight trains — often 100 cars or more — dedicated to carrying a single commodity, such as ethanol or crude oil.

These risks were on display two days later when a unit train hauling 100 cars of ethanol derailed on a bridge in Graettinger, Iowa, approximately 160 miles from Des Moines. This time, 27 of the cars left the tracks. At least eight tank cars ruptured and caught fire, and three tank cars ended up in a creek beneath the bridge, releasing about 1,600 gallons of ethanol into the waterway.

Due to multiple explosions at the derailed ethanol train, emergency responders chose to let the tank cars burn themselves out over the course of the weekend instead of risking approaching the fire. It isn’t hard to see what this type of accident could do in Providence or another populated area.

As DeSmog noted in a series last year, fewer ethanol train derailments historically have resulted in large fires and spills compared to oil trains — despite more ethanol being moved by rail over the same time.

However, after analyzing ethanol industry data and the trend toward shipping more ethanol via unit trains, DeSmog predicted an increase in fiery train derailments involving ethanol unit trains, which appear to be on the rise. No oil trains have derailed and ignited this year.

“Shippers want to utilize unit trains if they can to save money,” Tom Williamson, a broker and owner of Sarasota, Florida-based Transportation Consultants, told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. The paper reported that “11 of his 12 clients have switched to unit trains in the past two years.”

Ethanol and the Unsafe DOT-111 Car

When federal regulators set new rules phasing out unsafe DOT-111 tank cars for shipping oil and ethanol by rail, the risk of “bomb trains” carrying flammable Bakken crude oil received most of the attention. The ethanol industry, meanwhile, was given a much longer timeline to remove these tank cars from service, allowing use of the riskiest “non-jacketed” DOT-111 cars until 2023 and of jacketed DOT-111 cars until 2025.

In addition, no regulations dictate how long these ethanol unit trains of DOT-111 cars can be. The National Transportation Safety Board has been warning about the use of DOT-111 tank cars for decades and continued to sound the alarm after the latest accident in Iowa, as reported by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

“We would like to see the shippers accelerate their schedule to get these legacy DOT-111 tank cars out of service when transporting flammable liquids — specifically crude oil and ethanol,” said Robert Sumwalt, a member of the National Transportation Safety Board and the moderator of a July 2016 roundtable on oil and ethanol train safety.

However, as DeSmog reported last year, despite the oil industry’s faster phase-out deadline of 2018, it isn’t exactly hurrying to invest in retrofitting its existing fleet of tank cars. By mid-2016 the oil industry had only retrofitted 225 out of a fleet of 110,000 tank cars. And the industry is lobbying for additional loopholes to allow risky cars to remain in crude oil service indefinitely.

The Federal Railroad Administration did not respond to multiple requests for comment on the possibility of phasing out the use of DOT-111 tank cars faster than the current schedule.

Not only is the ethanol industry moving toward using more unit trains, it is using risky DOT-111 rail cars to do so. In his opening remarks to the roundtable in July, Robert Sumwalt explained that we should continue to expect many more fiery oil train derailments with the existing tank car fleet, saying, “just do the math.”

Now with the ethanol industry moving to embrace the oil-by-rail business model of longer unit trains, the same math applies. And the two accidents this month are perhaps the canary in the coal mine for the ethanol-by-rail industry.

What Have We Learned?

In July of 2013, a Bakken oil train derailed in the small Quebec, Canada, town of Lac-Mégantic, resulting in explosions and fire which killed 47 people and leveled its downtown. In December 2016, a conference was held in Ottawa to review the lessons learned from the Lac-Mégantic disaster.

Brad Stevens is currently National Rail Director for Unifor, Canada’s largest private sector union. At the conference he told attendees, “Nothing has changed. The railway barons are still there. And stronger than ever.”

However, as we can see with the recent derailments of two ethanol trains, things are changing. The rail industry is adopting riskier practices in pursuit of profits. This happened first with Bakken crude oil, then with ethanol, and — as reported by DeSmog — now the rail industry wants to start moving unit trains of liquid petroleum gas.

And all of this is happening as the Trump administration is poised to roll back safety regulations.

After the ethanol train accident in Providence, Cristina Cabrera, executive director of Environmental Justice League of Rhode Island, made a comment that echoed what we have heard after many of the oil train derailments.

“We are all very lucky that this accident did not result in a spill,” Cabrera said. “Which could have been disastrous.”

Other than the deadly disaster in Lac-Megantic, the oil, ethanol, and rail industries have been very lucky that none of the major derailments and fires have happened in populated areas. However, with the expansion of ethanol unit trains, the odds are that this luck will run out at some point, resulting in deadly consequences.

Just do the math.

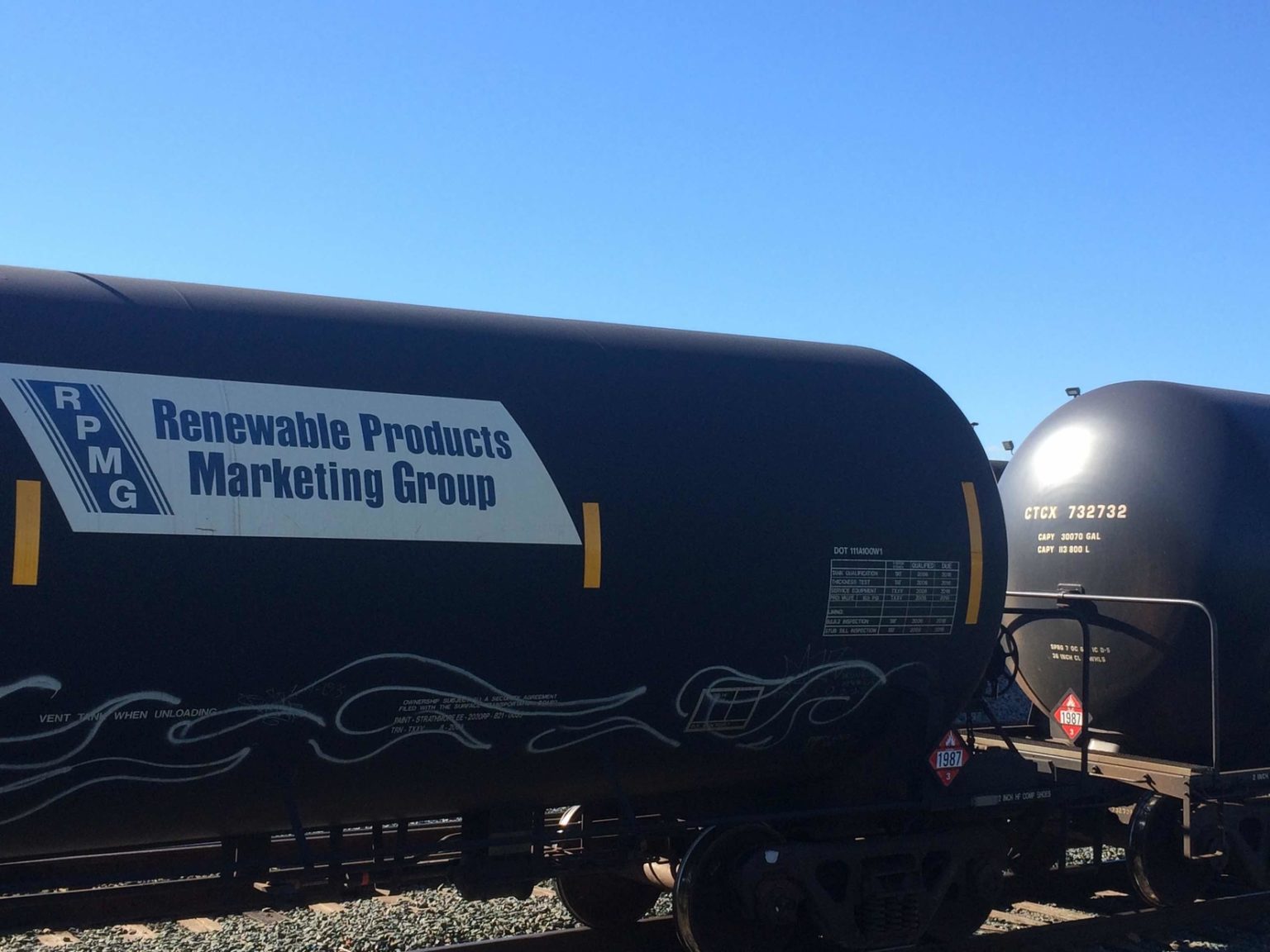

Main image: Justin Mikulka

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts