Don Blankenship, who just wrapped up a year in federal prison for criminal conspiracy to violate mine safety and health rules — a coordinated and concealed series of violations that lasted for at least 15 months leading up to the tragic Upper Big Branch mine explosion that killed 29 coal workers — emerged from his incarceration unrepentant, and none the humbler.

On Tuesday, the former CEO of Massey Energy released an open letter to President Trump urging the administration to ignore any legislation that would strengthen punishments for mining company executives and supervisors who knowingly flout safety rules.

“Coal supervisors are not criminals, and the laws they work under today are already frightening enough for them. More onerous criminal laws will not improve mine safety,” Blankenship wrote. He said that Congress “too often wants to punish coal companies, coal operators, and coal supervisors versus helping them to improve coal mine safety.”

Blankenship, who has never admitted to any wrongdoing and never apologized to the families of the workers killed in his mine, was convicted for “conspiracy to violate mandatory federal mine safety and health standards.” The explosion at the Upper Big Branch mine was the worst coal mining disaster in 40 years, and was labeled “entirely preventable” by the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration, which investigated the accident and found that the explosion was caused by “systematic, intentional, and aggressive efforts” to conceal, rather than fix, hazards.

Dubbed the “dark lord of coal country” by Rolling Stone, Blankenship was found guilty of overseeing the conspiracy to cover up these safety violations that created the dangerous conditions that caused the explosion. Before Blankenship, four other Massey supervisors had already been convicted for their roles in the conspiracy, including, as DeSmog reported in 2014, “the Upper Big Branch mine superintendent who admitted he disabled a methane monitor and falsified mine records. And while lower-ranking supervisors received sentences measured in months, Blankenship’s closest subordinate was sentenced to three and a half years for his role in the tragedy.”

Blankenship’s conviction was punished with a one year sentence in federal prison, which is the maximum for this particular crime, as Ken Ward Jr. of the Charlestown Gazette-Mail explained:

“Under federal law, violating or conspiring to violate mine safety and health standards is classified as a misdemeanor, or a minor crime, with a maximum jail sentence of one year. Mine safety advocates have been urging Congress for years to make such crimes felonies, but the legislation has made little progress.”

In his letter, Blankenship calls a proposal by West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin to increase criminal liability for coal mine supervisors to be “a prime example of bad legislation.”

He may also have been motivated by a recent statement by Virginia Representative Bobby Scott, a ranking member of the House Education and the Workforce Committee, who advocated for harsher criminal penalties for the violation of federal mine safety laws. Rep. Scott wants to make the willful violation of mine safety rules into a felony offense that could carry up to a maximum five year sentence, a far stiffer penalty than the one year maximum currently allowed as a misdemeanor.

When reintroducing the Robert C. Byrd Mine Safety Protection Act in April, Rep. Scott wrote:

The release of the former Massey CEO who served the maximum possible sentence of only one year for willfully violating mine safety standards that led to the Upper Big Branch Mine disaster should serve as a reminder that the criminal provisions in the Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977 remain woefully inadequate … The maximum penalty for the willful violation of a mandatory health and safety standard is a mere misdemeanor — rather than a felony — regardless of the number of miners killed because of criminally reckless conduct.”

The Two Dons

Blankenship clearly sees in President Trump a kindred spirit. In his letter, he wrote:

“You and I also share something. We share relentless and false attacks on our reputation by the liberal media. The attacks on me have been relentless since 1985 when the miners at a group of mines I supervised chose to decertify their union membership. I am hopeful that in considering this request to improve coal miner safety, you will put aside the media’s false claims about me and help me expose the truth of what happened at the Upper Big Branch (UBB) coal mine in West Virginia on April 5, 2010.”

Like the President, Blankenship refuses to acknowledge facts that don’t agree with his personally crafted narrative, and dismisses investigations that betray his account of what caused the explosion.

Sen. Manchin, MSHA lied about deceased miners. Forced miners to reduce air and then said miners were at fault. Shameful!!!!

— Don Blankenship (@DonBlankenship) May 10, 2017

And like the President, Blankenship has taken to Twitter to not only defend himself (with 11 tweets on the day of his release and at least 43 tweets in less than a week since) but also to peddle conspiracy theories — blaming the regulators themselves for the fatal explosion, theories that have been disproven by four separate investigations. After he was convicted, Blankenship self-published a book called An American Political Prisoner.

Again, like the President, Blankenship endears himself as a hero to the working class, though the communities where his mines operate have been left in ruin, their economies shattered, their drinking water poisoned, and their workers left sick and dead.

“I shared most of my life with coal miners and I owe them a great debt,” Blankenship wrote in his letter to Trump. However, the former coal CEO did not make mention of any plan to repay that debt with the $80 million golden parachute he received when he was forced to resign from Massey in disgrace.

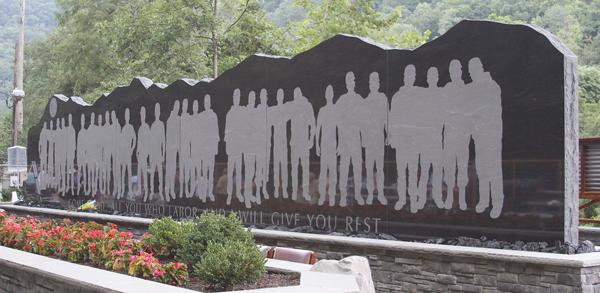

Main image: Upper Big Branch Memorial in Whitesville, West Virginia. Credit: United States Mine Safety and Health Administration, public domain

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts