With the next round of United Nations climate talks scheduled for November, eyes will be trained on how the United States chooses to engage — or not — now that President Donald Trump is withdrawing the country from the landmark Paris Climate Agreement. Yesterday, Secretary of State and former ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson indicated that this process will not happen through the State Department’s Special Envoy for Climate Change, because, well, he’s scrapping the position.

In a letter to Senate Foreign Relations chair Bob Corker (R-TN), Tillerson wrote, “I believe that the Department will be able to better execute its mission by integrating certain envoys and special representative offices within the regional and functional bureaus, and eliminating those that have accomplished or outlived their original purpose.”

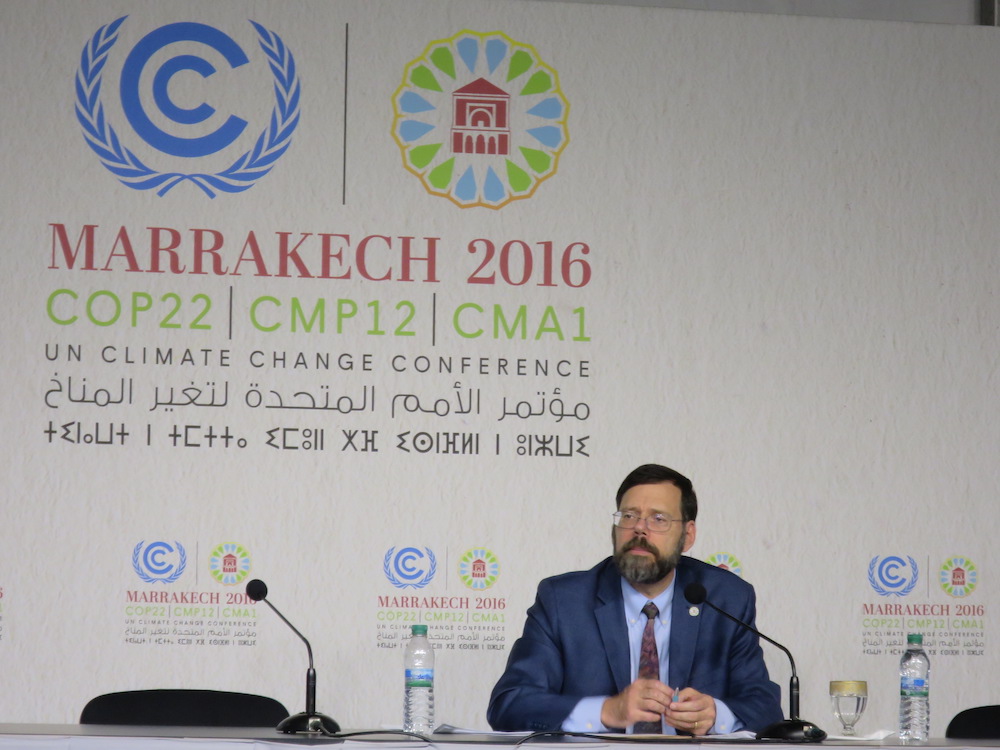

“The position of climate envoy was established by Barack Obama in 2009 and was filled by Todd Stern until 2016. The envoy for Obama’s last year in office was Jonathan Pershing, who left the political appointment when the government changed in January this year.

The special envoy was the US’ diplomatic figurehead, a position Stern used to become one of the major forces behind the eventual shape of the Paris deal, right down to the 11th hour wrangling over a troublesome ‘typo’ in the text.”

State Department Scales Back on Climate

The move came as part of a larger streamlining and reorganizing of the State Department, which for months has been scaling back its focus on climate issues.

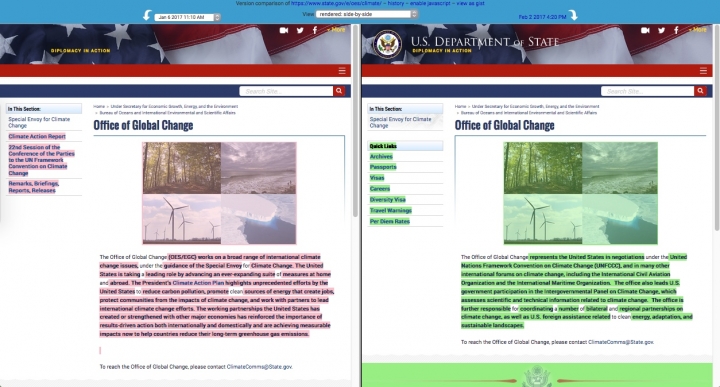

Shortly after Trump’s inauguration, the State Department’s web page for the Office of Global Change, which operates under the climate envoy, switched up its description, replacing most of the original text with more passive language.

The Office of Global Change web page, before (left) and after (right) its alterations by the Trump administration. Credit: Environmental Data & Governance Initiative

Climate Central noted the changes:

“Deleted from the text was: ‘The United States is taking a leading role by advancing an ever-expanding suite of measures at home and abroad.’ Also stricken were references to mitigation efforts and other mentions of leading on climate change.

In its place is more generic language, solely referencing that the office represents the U.S. at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and other international forums. It does use the word ‘lead’ once, but only saying the office leads the U.S. government in participating with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.”

Interestingly, the climate envoy’s main web page still notes the following, showing just how at odds its existence is with the current administration’s priorities: “The Paris Agreement is the most ambitious climate accord ever negotiated, and its rapid entry into force demonstrates the commitment and urgency of the international community to work together as it grapples with the growing threat of climate change.”

These largely cosmetic changes in how the State Department described its role in climate negotiations were apparently an early warning sign, with many more that followed. In March, executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Patricia Espinosa was reportedly given the cold shoulder when she requested a meeting with Tillerson and other officials during a trip to the U.S. The complete lack of response to Espinosa’s request was considered unusual.

At the time, the Trump administration was considering what would become its eventual withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, and a State Department official told the Guardian, “As with many policies, this administration is conducting a broad review of international climate issues.”

Pulling out of Paris

During the 2016 UN climate talks, Special Envoy Jonathan Pershing refused to guess how the new administration might deal with the Paris Agreement, saying in November that year:

“It’s premature to speculate. The new administration may look at the commitment globally, at the interest globally in the issue, and decide how it can move forward in ways that are consistent with its own policies.”

Of course, this position was clarified with Trump’s June 1 announcement that he would initiate the withdrawal of the U.S., the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide in history, from the Paris Agreement.

Then, on August 4, Tillerson sent a diplomatic cable to U.S. embassies, instructing them to dodge questions on the administration’s intent to renew engagement with the international climate accord. State Department guidance stated that “there are no plans to seek to re-negotiate or amend the text of the Paris Agreement.” However, it instructed embassies to provide vague answers about “considering a number of options” but not having information “to share on the nature or timing of the process.”

Yet the same cable revealed that the U.S. plans to attend the global climate talks, reportedly to look out for U.S. interests, as it undergoes the multi-year process of withdrawing from the Paris Agreement.

Instead, it encouraged diplomats to emphasize U.S. support for fossil fuel projects, a move reversing the Obama era policy of, for example, withholding support for financing global coal projects. According to Reuters, the cable suggested explaining that “[t]he new principles will allow the [United States] the flexibility to approve, as appropriate, a broad range of power projects, including the generation of power using clean and efficient fossil fuels and renewable energy.” [Emphasis added.]

Looking Ahead

With the disbanding of the climate envoy position, the U.S. will likely occupy an even weaker position at this year’s upcoming UN climate talks in Bonn, Germany. Interim talks in May saw a notably tiny U.S. delegation from the State Department and White House.

However, filling the vacuum left by the federal government, multiple U.S. states, hundreds of cities and counties, and more than 1,600 businesses have pledged to uphold the nation’s commitments to the Paris Agreement.

“To see states and cities in the U.S. and territories and regions around the globe align their ambition and plans with the aims of the Paris agreement is almost unprecedented in the history of U.N. environmental treaties,” Nick Nuttall, UNFCCC director of communications and outreach, told ThinkProgress in July.

Main image: Previous climate envoy Jonathan Pershing at the UN climate talks in Marrakech, Morocco, in November 2016. Credit: Ashley Braun, DeSmog

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts