Thirty years ago, oil company Shell was warned in private that its own products were responsible for climate change which in turn could lead to large scale climate migration.

Yet over the following decade, the company publicly justified the ongoing need for fossil fuels as the only realistic way to achieve sustainable development and lift vulnerable communities out of poverty.

Shell has repeatedly used the arguments of population growth and increasing energy demand at the heart of its public pronouncements about its role in driving economic and sustainable development.

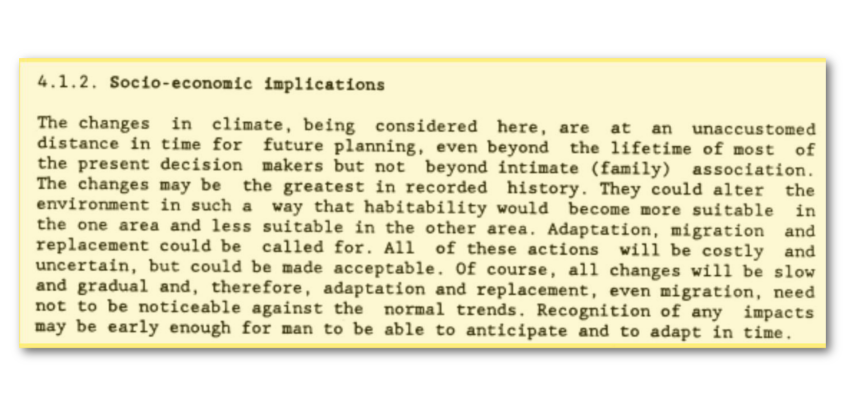

But Shell also knew that burning fossil fuels would “alter the environment in such a way” that it would affect parts of the world’s “habitability” and could lead to new migration patterns.

There is a clear relationship between climate change and forced migration as crops fail and extreme weather increases. But recent research also points to the impossibility of separating climate change from the myriad of other factors that drive people to leave their homes.

Documents first uncovered by Jelmer Mommers of De Correspondent, and published on Climate Files, show the discrepancy between what Shell was told in confidence and what it decided to say in public. Throughout the 1990s, the documents show that Shell failed to mention in public that burning fossil fuels could result in people being forced to leave their homes because of sea-level rise and that entire regions of the world could be made uninhabitable.

1988: ‘Parts of the world could become uninhabitable’

DeSmog UK previously reported on a confidential 1988 report called the Greenhouse Effect, which showed that Shell knew about the impact its fossil fuel products were having on climate change. The report also set out how climate change consequences, such as sea level rise, could have a direct impact on people’s livelihood and migration patterns.

The report used the example of Bangladesh to illustrate this point. In recent years, Bangladesh has seen dramatic flooding events forcing hundreds of thousands of climate refugees out of their homes and into emergency shelters.

Last year, Bangladesh’s prime minister Sheikh Hasina told the UN that a one-metre rise in sea level – a plausible scenario this century – would submerge a fifth of the country and turn 30 million people into “climate migrants”.

Shell acknowledged that climate change impacts “may be the greatest in recorded history” and “could alter the environment in such a way that habitability would become more suitable in some areas and less suitable in others”. The document highlights migration as a potential necessary consequences of these changes.

At the time, Shell was also advised that in order to reconcile providing energy for a fast-growing global population and resolving the environmental impact from energy production, it had to “adopt a common policy for energy and the environment”.

But despite Shell being told early on about what impact climate change could have on migration patterns and the movement of people globally, its rhetoric throughout the next decade continued to promote the use of fossil fuels as the only effective way to meet global energy demand.

1992: ‘Three cornered challenge: energy, environment and population’

In a 1992 speech in London, president of the Royal Dutch Shell group and chairman of its supervisory board Lodewijk Christiaan van Wachem told the audience the company was facing a threefold challenge: “the world’s increasing demand for energy, the growth of the world’s population and the need to safeguard a viable world for future generations”.

Van Wachem added that to respond to this challenge, Shell had to “establish a sustainable pattern of growth” with the following caveat: “there are not the resources to do everything at once [raised environmental standards and increase energy consumption]”.

The speech did not mention what Shell knew in private, that global warming and resulting sea level rise could lead to significant migration flux.

For Van Wachem, meeting growing energy demand had to take precedence over environmental concerns and Shell had to continue to burn fossil fuels. He added that the “degree of freedom to choose between them [the least and better fossil fuel options] will be limited”.

Shell recognised that “it may be that no demands to improve the condition of even the poorest communities justify the profligate or unwarranted use of energy”. But it powered trough with one single message that economic growth, sustainable development and fossil fuels were intrinsically linked.

Van Wachem acknowledged that “some renewable energy look promising” but that they will take time to become a competitive force in the market.

To give more weight to his argument of economic and sustainable growth over ambitious climate action, he downplayed what the company already knew about climate science and stressed the “debate among authoritative individuals and groups about the basic science” and its impacts in different parts of the world.

Although Shell was aware of the potential for climate-induced migration, the company continued to see population growth as expanding market opportunities for its own products, which it said would lead to economic development.

1994: Frontier markets

In a report titled “Energy for development”, Shell presented different scenarios to meet growing energy demand until 2020.

The company saw booming population and the rising demand for energy as an opportunity to launch its business into frontier markets and bring oil, gas and coal — the dirtiest form of fossil fuels — to developing countries.

DeSmog UK’s previously reported that confidential documents from the 1980s showed Shell knew coal produced more emissions than other fossil fuels and proposed to move away from it as a solution to tackle climate change.

‘Environmental action comes after economic development’

In a 1994 speech in Indonesia, Shell group managing director Mark Moody-Stuart insisted that while “we all suffer if economic activity degrades the environment” only oil and gas will foster development for future generations.

Here again, the consequences of climate change on people’s livelihood and the risk of creating “uninhabitable” parts of the world were not mentioned.

Instead, the focus was on “extracting the maximum” from each oil and gas development projects “and putting it to the best possible use”.

‘Increasing numbers of environmental refugees’

The same year, an internal Shell briefing on population, energy and the environment put the migration issue back at the top of issues highlighted to the company’s executives.

It recognised that “environmental pressures such as drought, soil erosion, desertification and other problems have increased the number of environmental refugees” alongside other socio and economic factors.

The briefing document went further and pointed out that migration driven in part by “environmental degradation” would increase social, economic and environmental pressures.

1997: ‘Sustainable Development and the challenge for energy’

In a presentation about Shell’s vision for sustainability, group director John Jennings repeated Shell’s message to the public that “there is no practical alternative for this timeframe” to meet energy demand with anything else but fossil fuels.

Instead, Jennings suggested history will remember the ongoing burning of fossil fuels as a “a primitive phase” and said there remained uncertainty behind climate science.

While Shell knew about the risk of climate change to vulnerable communities’ livelihoods, it continued to justify the burning of fossil fuels through its commitments to sustainable development — a goal itself threatened by Shell and other coal, oil and gas giants’ products.

For Shell, “an abrupt change to business activities” was not an option.

Today, the nexus between climate change, population and energy demand remains at the core of Shell’s business strategy.

A Shell spokeswoman told DeSmog UK: “We have long recognised the climate challenge and the essential role of energy in driving the world’s economy, raising living standards and improving lives. Yet there are still over one billion people in the world without safe, reliable access to energy or the basic benefits it provides.

“Society therefore faces a dual challenge of meeting growing demand for energy, while at the same time transitioning to a lower carbon world”.

The company has also done more work on migration to cities with people seeking access to resources such as energy and water and the resulting pressures on demand and sustainability.

But Andrew Pendleton, director of policy and advocacy at the think tank New Economics Foundation, accused Shell of failing to switch its business model despite knowing about the “human cost” and having “multiple opportunities to transform itself gradually into a different sort of energy business”.

He said: “Unfortunately, in knowingly continuing to seek profit from over-heating the earth’s atmosphere, it has probably already helped fulfil its own prophecies and also seal the fate of many people in low-lying countries and island nations [threatened by sea-level rise].

“Just like tobacco companies knowing about the links between smoking and cancer long before it was widely known in public, it turns out Shell knew the harm its products do to the climate when they’re burned and the human cost of the havoc that will wreak.”

In a statement, Shell said the issues of climate change and its causes had been part of public discourse for many decades.

“The suggestion that the Shell Group had unique knowledge about climate change is simply not correct. Our position on climate change has been publicly documented for more than two decades through publications such as our Annual Report and Sustainability Report,” Shell spokesman said.

Climate migration research

The link between migration and climate change is a complex one.

Alex Randall, who runs the research project Climate and Migration Coalition, told DeSmog UK there was “undoubtedly” a relationship between climate change impacts and the movement of people but that levels of wealth and infrastructure had to be taken into account.

“People have always been displaced by disasters such as hurricanes, droughts and flash floods. We can say that to some extent climate change has already altered patterns of migration,” he said.

Randall added that recent research accepted that the majority of climate-linked migration will be internal and short distance, rather than long distance and across international borders and that climate impacts are one driver among many other socio-economic factors for people to move.

“This research still regards, climate change impacts as an important dimension to migration — now and in the future,” he said.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts