This week, a Trump official at the U.S. government’s pro-fossil fuel event at the United Nations climate talks made clear that the idea of burying carbon emissions from coal plants is still alive.

Wells Griffith, an advisor to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), said at the event: “For the U.S. energy policy, it’s not about keeping [fossil fuels] in the ground but about using them cleanly.”

Griffith added: “Alarmism should not silence realism. This is a forum for fact science-based discussions on climate realities.”

His conclusions make for great talking points, but they’re far from reality. After more than a decade of failed demonstration projects, a recently rescinded $1.1 billion DOE research program, and the Trump administration’s move to roll back requirements that all new coal plants have “carbon capture and storage” (CCS) capabilities, the promise of so-called “clean coal” technology is dead.

For quite some time now, both the coal industry and the U.S. government have been obsessed with the idea of making coal less harmful by pursuing various carbon capture technologies. With scientists ringing the alarm bells as the planet warms, the coal industry is once again trotting out the idea that it can clean up its act using space age technology to capture and sequester carbon before it pours out of smokestacks.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration can’t seem to make up its mind whether it’s for CCS or not.

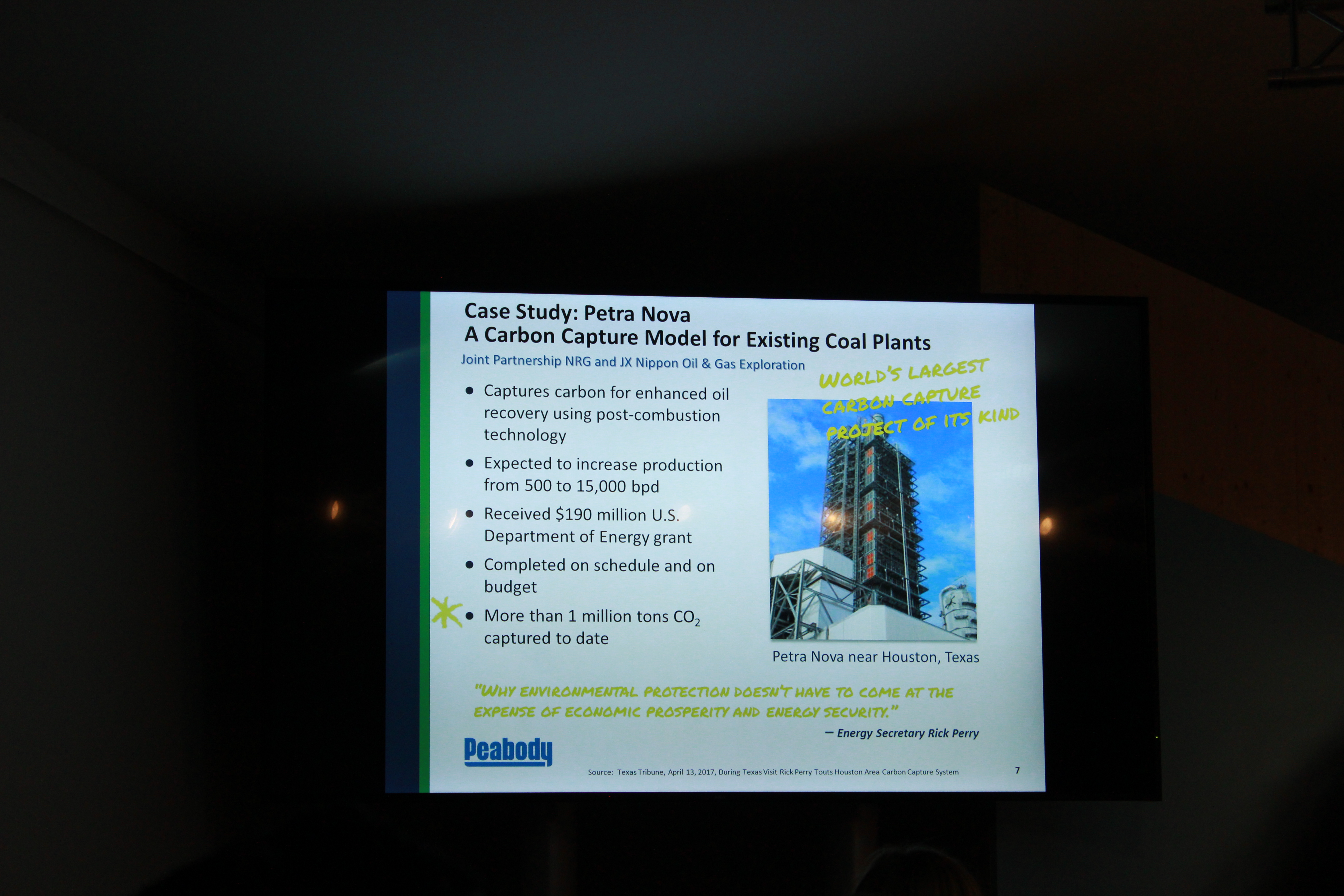

A slide from Peabody’s presentation on coal and carbon capture and storage at the Trump administration’s event at the 2017 UN climate talks. Credit: Ashley Braun, DeSmog

The Journey to ‘Clean Coal’: Expensive and Fruitless

Today, burning coal remains one of the most harmful ways to generate electricity, in terms of human health and the health of the planet. With the rapid scaling up in production and refinement of renewable energy technologies, continuing to seek a high-tech silver bullet to make coal less polluting is not only becoming a relatively expensive endeavor, it is proving to be a fruitless one.

A September* 2018 report produced by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) has found that the DOE has spent $2.66 billion over the last seven years to find “advanced fossil energy technologies” and figure out how coal can work in a carbon-constrained world.

Credit: Petra Nova, a joint venture between NRG Energy and JX Nippon Oil & Gas Exploration, via the U.S. Energy Information Administration

With massive cost overruns, delays, and complications evident early on with these coal CCS technologies, it was clear to many observers that capturing and storing coal’s carbon emissions was an overly complicated solution that could likely never be deployed at a commercial scale.

In 2009, Jeff Goodell, Rolling Stone contributing editor and author of the book Big Coal: The Dirty Secret Behind America’s Energy Future, wrote that:

“The truth is, there is no viable way to scrub carbon pollution from coal plants. The industry touts a technology called ‘carbon capture and storage,’ which can, in theory, collect carbon dioxide from smokestacks and bury it underground … Contrary to Obama’s optimism, it’s unlikely the technology will be ready for commercial deployment within 20 years, much less a single decade.”

But observations from astute journalists and other experts like Goodell fell on deaf ears. The U.S. government, including under President Obama, spent big dollars pursuing what many at the time knew was a ridiculous hazy-eyed techno dream.

Where Are the ‘Clean Coal’ Power Plants?

Of the $2.66 billion committed by the DOE for advanced fossil energy technology development, almost half of those funds ($1.12 billion) was allocated to nine demonstration projects with the goal of figuring out a way to capture the greenhouse gas emissions from burning coal and storing those emissions underground permanently. Carbon capture and storage is something DeSmog has researched and written about for over a decade.

According to the GAO report, of the nine CCS demonstration projects all but three have failed, and of those three only one is an actual power plant.

As of today, the one remaining project in the entire world that can capture carbon from burning coal is the Petra Nova project in Texas. Up until July 2018 there were actually two, but the project known as Boundary Dam in Saskatchewan, Canada, was scrapped by the government because it didn’t make economic sense. And of course, in June 2018, Southern Company announced potentially billion-dollar losses along with the news it was scrapping its clean coal plans at its Kemper County, Mississippi, power plant.

At the U.S. pro-fossil fuel event during the 2017 UN climate talks, Peabody highlighted the Petra Nova CCS project. Credit: Ashley Braun, DeSmog

But Petra Nova does not bury greenhouse gas emissions in a way that is very helpful to the climate.

The plant uses captured emissions to do what is called “enhanced oil recovery” — pumping captured gases into older oil deposits to recover more oil, which is then processed and burned up in the atmosphere. Even if this seems somewhat promising, the Petra Nova project can only capture about 33 percent of greenhouse gas emissions it produces, at a development cost so far of more than $1 billion.

Another carbon capture project often cited by U.S. government officials and a coal industry keen on hyping the idea of CCS was the FutureGen project to be constructed in Meredosia, Illinois. In 2005, when the DOE announced an investment of $1 billion for FutureGen, the project was touted as “a prototype of the fossil-fueled power plant of the future.”

In 2015, FutureGen was officially canceled when the DOE suspended its funding, citing an inability of the project to meet its deadlines and major cost overruns.

The world now has fewer coal CCS projects than ever in the last decade. If CCS were a technology on the rise, this would not be the case. It would also not be the case that a major research program examining CCS projects at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) would be shut down.

An MIT research unit called the “Carbon Capture and Sequestration Technologies program” analyzed and tracked the progress of carbon capture projects worldwide. It was a great tool to watch the implosion of the clean coal dream. Year after year, projects listed on the MIT website went from being listed as “under construction” or “in progress” to “canceled” and “on hold.”

As of September 2016, the MIT Carbon Capture and Sequestration Technologies program itself was canceled. A further sign that CCS is not the burgeoning technology that government and industry had hoped it would become.

MIT‘s web page announcing the end of its Carbon Capture and Sequestration Technologies program.

The U.S. government is also losing interest in supporting the CCS dream, at least in some venues. As first reported by Bloomberg, Trump’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) last week proposed reversing an Obama-era rule essentially requiring that new coal plants use carbon capture technologies.

But during the U.S. pro-fossil fuel event this week, DOE Assistant Secretary for Fossil Energy Steven Winberg reiterated that the U.S. had been working to develop CCS and CCUS (carbon capture usage and storage) technology for years and that would continue to be the case in the future.

A lot of money and time has been spent trying to prove a technology that many from the start knew was unprovable. As someone deeply concerned about the state of our planet, I would like to be able to claim otherwise, but the time has come to admit that CCS for coal is dead.

Sometimes it just takes a little longer and few billion dollars for some to admit a mistake.

Updated 5/21/19: This story has been updated to reflect that this GAO report was published in September 2018, not October.

Main image: Majuba Power Station, South Africa, April 2, 2013. Credit: Gavin Fordham, CC BY–NC 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts