By Isabella Kaminski, Climate Liability News. Originally published on Climate Liability News.

The world’s biggest polluters could be held legally liable for their contributions to climate change, a major national inquiry into the links between climate and human rights has concluded.

The Philippines’ Commission on Human Rights announced its conclusion on Monday following a nearly three-year investigation into whether 47 of the world’s biggest fossil fuel firms — known as the Carbon Majors — could be held accountable for violating the rights of its citizens for the damage caused by global warming. The commission was responding to a 2016 petition from Greenpeace South-East Asia and other local groups.

Commissioner Roberto Eugenio T. Cadiz said the commission found these companies, which include ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, BP and Repsol, played a clear role in anthropogenic climate change and could be held legally liable for its impacts. He made the announcement during the United Nations climate talks in Madrid (COP25).

Legal responsibility for climate damage is not covered by current international human rights law, Cadiz said the commission had found, but fossil fuel companies have a “clear moral responsibility.” He said it would be up to individual countries to pass strong legislation and establish legal liability in their courts, but that there was clear scope under existing civil law in the Philippines to take action.

Cadiz said it may also be possible to hold companies criminally accountable “where they have been clearly proved to have engaged in acts of obstruction and willful obfuscation.”

The report also concludes that carbon majors “definitely have an obligation to respect human rights” as enunciated under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, and a clear responsibility to invest in clean energy.

The commission’s findings had originally been due last summer. Cadiz told Climate Liability News that commissioners agreed with the general conclusions but were still wrangling over details regarding liability, and the final report would be published by the end of the year.

Yeb Saño, executive director of Greenpeace South-East Asia and one of the petitioners in the inquiry — formerly a climate negotiator for the Philippines — told Climate Liability news he was very pleased by commission’s conclusions, which he said were stronger than expected.

Carroll Muffett, president of the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), said the commission’s recognition that there is evidence of criminal intent in the companies’ climate denial and obstruction is “particularly significant and a major development for the carbon majors.”

“Both for civil and criminal liability in jurisdictions around the world, the commission’s findings in this inquiry represent not an end of the legal investigations into carbon majors companies but a major new beginning for them,” Muffett said.

The commission’s recommendations do not carry direct legal weight. But they could lead to tougher regulations and put pressure on companies to cut their emissions in the Philippines and elsewhere. “Our findings can be relied upon as a precedent for parties that seek social justice on the issue of climate change,” Cadiz said during another event at COP25.

Cadiz said national human rights institutions are “ideally situated to deal on issues that regular courts would normally not touch or are not familiar with.”

When the commission began its investigation in 2016, Cadiz said the regular judicial system provided no clear precedent on the issue. “There was no case that we could look into where climate change has been framed as a human rights issue,” he said. “But because we are a national human rights institution, we have more leeway in being creative and imaginative in how we promote human rights. We were able to create our own processes.”

The commission held hearings in Manila, New York and London, where evidence was presented by climate scientists, legal experts, academics and survivors of climate-related disasters. Recognizing that climate change is a global issue with no territorial boundaries, “there was nothing to stop us turning it into a global conversation,” Cadiz said.

Human rights have become a hot topic at COP25, where heated discussions have been held about how to ensure negotiations on carbon market rules and loss and damage provisions respect the wider ethical dimensions of climate change.

A CIEL report released last week found a growing number of explicit and implicit references to human rights in climate agreements and policies adopted under the adopted under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

“This intersection is also recognized by various human rights bodies, including treaty bodies, UN special procedures mandate holders, courts, and national human rights institutions,” it said.

Also speaking at COP25, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet said climate change and environmental degradation “directly and indirectly interfere with the enjoyment of all human rights” and noted that governments and the general public are increasingly seeking to hold businesses accountable for the climate crisis.

“Across the world, people and communities have taken to the streets and used strategic litigation to demand climate justice, and these movements can only grow.”

This movement had met “considerable resistance” from the corporate world, Bachelet said, with large fossil fuel producers undermining scientific work on climate change and international action.

Both Bachelet and Cadiz stressed that it was important to examine the role of state-owned fossil fuel firms as well as privately owned companies.

“If you just hit the private carbon majors then state-owned carbon majors will take up the slack,” Cadiz said. He said they “must also be held accountable for respecting and being guided by the … Paris Agreement and the IPCC.”

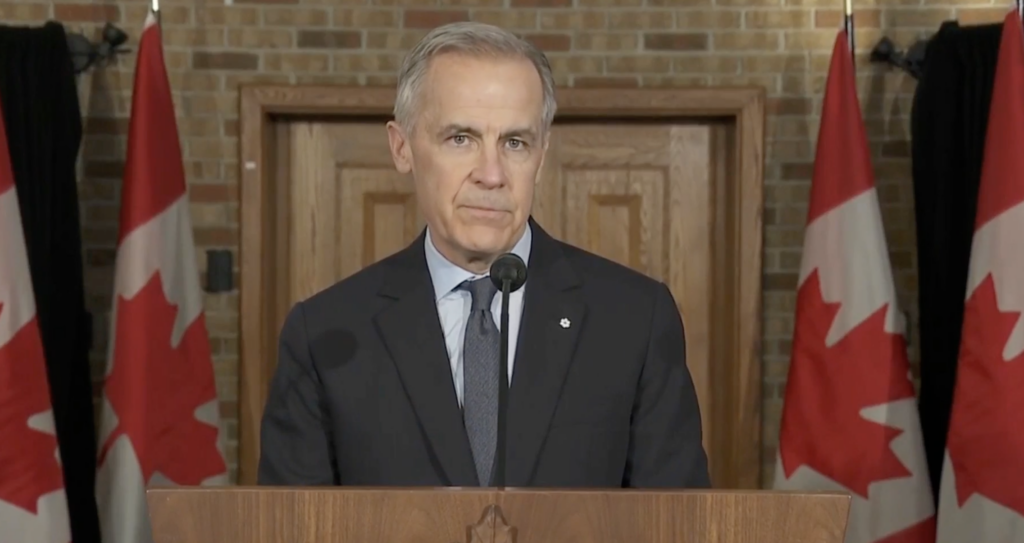

Main image: Calls for climate justice at a Dakota Access pipeline protest in Minnesota in 2016. Credit: Fibonacci Blue, CC BY 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts