The COVID-19 pandemic hasn’t changed life much for Chris Burnet, a lifelong resident of Isle de Jean Charles, a quickly eroding strip of land among south Louisiana’s wetlands. Though the island, about 80 miles southwest of New Orleans, can’t be saved from the sea-level rise and coastal erosion that’s been intensified by climate change, Burnet is happy he still lives there, even though his days there are numbered. Besides loving life on the island, he believes its remoteness has kept him and the remaining island residents safe from the coronavirus.

The Isle de Jean Charles received worldwide attention in 2016, when the Isle de Jean Charles Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw (IDJC) Tribe helped the State of Louisiana secure a $48 million federal grant to resettle the island’s residents, who face increasing danger with each hurricane season.

The land loss the island faces is a problem for all of Louisiana’s coastal communities, thanks to a combination of levee construction, coastal erosion, sinking land, rising seas, and damage from hurricanes worsened by climate change. About 16 square miles are lost from Louisiana’s coast each year.

Chris Burnet is a member of the IDJC Tribe, like the majority of the residents on the island. The tribe, along with other south Louisiana tribes, have been spared much of the ravages of the pandemic so far, which tribal leaders attribute to their remote locations, luck, and tribal members’ willingness to practice social distancing to prevent the virus’s spread.

I met with Burnet outside of his island home on May 12. He only recently opted to join the majority of the island’s residents in signing up for a free home in the state’s Isle de Jean Charles resettlement project — a decision he grappled with for years.

Chris Burnet with his dogs under his home on the Isle de Jean Charles.

He plans to move to Schriever, Louisiana, 40 miles north of the island, when the first homes in the development are completed. The first phase of construction began earlier this month.

Though Burnet doesn’t regret signing up for a new house, he is not in a hurry to leave the island. “The question ‘Should I stay or should I go?’ still rattles around in my head,” he said. With no cure for the pandemic on the horizon, the remoteness of the island continues to appeal to him.

IDJC Chief Albert Naquin played a large role in helping the state’s Office of Community Development (OCD) win a grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in the $1 billion National Disaster Resilience Competition. That grant was intended to build the island resettlement project. But while the winning proposal was based on Naquin’s vision of a tribal-led community, shortly after securing the grant, Louisiana’s OCD radically changed the original plan, resulting in Naquin withdrawing the tribe’s support of the project.

The original proposal focused on the IDJC Tribe, whose members have been scattering from the disappearing island for years, though they still represent most of the remaining island residents. The OCD explained that the changes were made to comply with HUD rules, and that the project’s focus had to be on the island residents, not one particular tribe.

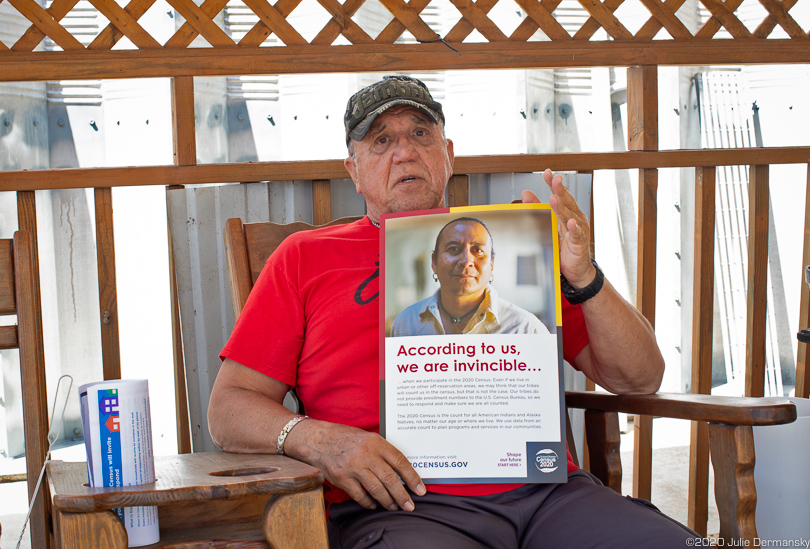

IDJC Traditional Chief Albert Naquin outside his home in Montegut, eight miles from the Isle de Jean Charles, with a poster from the Census Bureau and other informational handouts he has not yet been able to pass out.

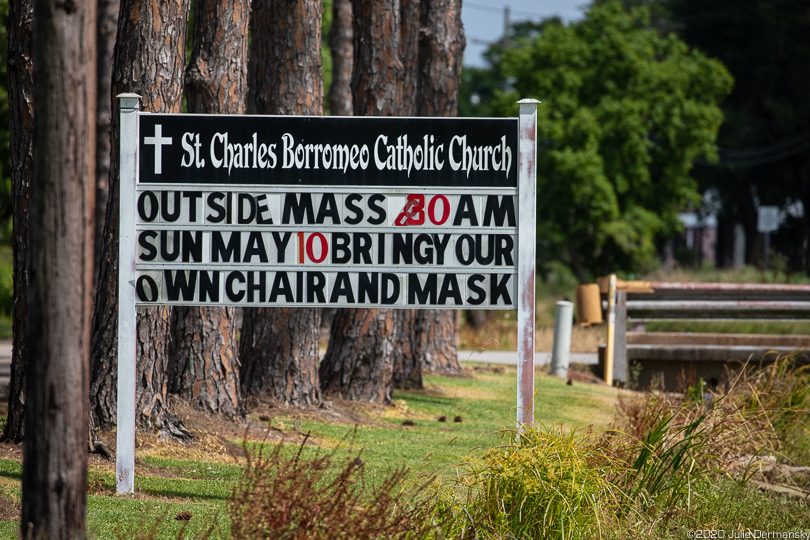

Sign at the church Naquin attends near his home in Montegut. Though services are now being offered outside, Naquin is still isolating at home.

At first, Naquin advised tribe members not to take the new houses offered by the state because of numerous shortcomings he found with Louisiana’s version of his plan. He intends to go back to the drawing board and raise funds to realize the tribe’s original resettlement project, which would reunite his far-flung tribe into a central, sustainable tribal community. But he changed his tune last year after Hurricane Barry’s storm surge swamped the island, leaving it submerged for a couple of days.

“It will take years before I can get funding to resettle the tribe as we originally planned,” Naquin said. “Barry made me realize that it is more important to get the tribe members to safer ground, than for them to hold out until I can create a settlement like the original proposal called for.”

Now he is actively encouraging the few holdouts on the island to take the state’s offer of a free home, despite the deadline to sign up for the resettlement project lapsing. He believes the state will still let late-deciders get a house.

Marvin McGraw, OCD’s communications director, confirmed the state has flexibility for late signers of the deal. “We have always said that we want to make this opportunity available for as long as we can,” McGraw wrote in an email. “There is a deadline for expenditure of the funds, so there will be a date after which we can’t accept any new applications, just by virtue of the fact that we would not be able to process the application and get the home built before the deadline.”

Despite Naquin’s new stance, he remains concerned that the OCD’s plan could cause hardships for tribe members. Some hope to continue to keep up their island residences as recreational fishing camps, even though they have to give up the right to reside on the island. However, few have the money to maintain two houses.

And though the resettlement project’s homes will be provided for free, some might not be able to pay the taxes and insurance required for them to remain in good standing with the state. These expenses will likely be a large increase compared to what residents now spend living on the island, which Naquin worries could result in some of them ending up homeless.

The pandemic is amplifying his concerns because some tribe members have lost their jobs and were already struggling financially. The state’s resettlement plan, unlike the plan proposed by the tribe, doesn’t include a safety net for tribe members who can’t support themselves. Naquin’s original proposal included a tribal-run community center that would generate income for those members who fall short.

Traditional Chief Shirell Parfait-Dardar of the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe, at her father’s grave in Dulac, Louisiana.

Shirell Parfait-Dardar, Chief of the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe, has followed the Isle de Jean Charles resettlement project since the start. Her tribe, like other coastal communities, also faces the inevitable need to relocate due to sea level rise quickened by climate change. She lives in Dulac, about 30 miles west of the island, in an area that she recently learned could be underwater in as little as 20 years, despite a recently constructed storm protection project.

In January, after watching Naquin’s proposal for his tribe get derailed, Chief Parfait-Dardar, along with three other Louisiana tribes and one Alaskan tribe, filed a complaint with the United Nations against the United States government for its failure to protect tribal nations against climate change. The complaint states: “By failing to act, the U.S. government has placed these Tribes at existential risk,” and asks the UN to intervene.

The Louisiana tribes that signed the complaint include the IDJC Tribe, the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe, the Grand Caillou and Dulac Band of the Biloxi-Chitimacha Choctaw Tribe, and the Atakapa-Ishak Chawasha Tribe of the Grand Bayou Indian Village in Louisiana, joined by the Native Village of Kivalina in Alaska.

The complaint states: “The United States government’s failure to protect the Tribal Nations named herein has resulted in the loss of sacred ancestral homelands, destruction to sacred burial sites, and the endangerment of cultural traditions, heritage, health, life, and livelihoods. Furthermore, it has interfered with tribal nation sovereignty and self-determination, and is breaking apart communities and families.”

Theresa Dardar, a member of Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe, one of the four Louisiana tribes that signed the complaint sent to the United Nations.

Theresa Dardar, a member of Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe, told me that they haven’t heard anything back from the UN yet but that is no surprise due to the pandemic.

The Louisiana tribes are seeking federal status to shore up their rights. Having only state recognition puts them at a disadvantage when it comes to protecting their ancestral land, pursuing financial assistance, and having a say in decision-making about coastal restoration projects, according to Patty Ferguson-Bohnee, a member of the Pointe-au-Chien Tribe and director of the Indian Legal Clinic at Arizona State University.

Chiefs Parfait-Dardar and Naquin worry that the COVID-19 pandemic will make getting federal status more difficult. The chiefs had planned to help tribe members fill out their census applications to ensure their population would be part of the official federal record, but that isn’t possible with the need for social distancing.

The U.S. Census Bureau has adjusted 2020 Census operations, but, despite Louisiana starting to reopen its economy, the tribes are still encouraging their members to self-isolate because many are elderly and have health issues that make them more susceptible to the coronavirus.

“Climate change is eventually going to impact everyone,” Chief Parfait-Dardar told me, while standing next to her father’s grave in a cemetery that will likely be submerged in the coming decades. It is her role to protect and preserve her tribe’s culture, but her concern is more far-reaching than that. “We are all one people — whether we chose to see it or not,” she said. “We need to stop climate change to stop its negative impacts and work toward greener solutions.”

Chris Burnet expressed similar sentiments. In front of his house is a toilet bowl with a sign on it that says: “Climate Change Not Worth.” He likens the impacts of climate change to “crap,” hence his “climate commode.”

Main image: Chris Burnet outside of his home on the Isle de Jean Charles. Credit: All photos by Julie Dermansky for DeSmog

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts