Human rights experts appointed by the United Nations Human Rights Council issued a statement on March 2 raising concerns about the further industrialization of Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley.” This largely Black-populated stretch of the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge is lined with more than a hundred refineries and petrochemical plants. The experts said additional petrochemical development in this region, which U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) data shows has some of the country’s highest cancer risks from air pollution, constitutes “environmental racism” that “must end.”

“This form of environmental racism poses serious and disproportionate threats to the enjoyment of several human rights of its largely African American residents, including the right to equality and non-discrimination, the right to life, the right to health, right to an adequate standard of living and cultural rights,” the experts said.

The statement calls for U.S. officials to reconsider allowing FG LA LLC, a subsidiary of Formosa Plastics Group, to build its proposed “Sunshine Project” in St. James Parish, in the middle of the region. That development, one of several new petrochemical projects slated for the region, would be a massive complex. Its 14 units would produce two types of plastic and the petrochemical ethylene glycol, which is used to make polyester fabrics and antifreeze.

It is a development that Sharon Lavigne, founder of the faith-based grassroots organization RISE St. James, has been trying to stop ever since learning in 2018 that the company planned to build its complex less than two miles from her home.

Sharon Lavigne of RISE St. James with a display of photos from her ongoing fight against the encroaching petrochemical industry in St. James Parish.

If built, “Formosa Plastics’ petrochemical complex alone will more than double the cancer risks in St. James Parish affecting disproportionately African American residents,” the human rights experts wrote. Their statement also took government regulators to task for their role. “Federal environmental regulations have failed to protect people residing in ‘Cancer Alley,’” they said, calling for the U.S. Government “to deliver environmental justice in communities all across America, starting with St. James Parish,” by stopping the Formosa Plastics project.

Jane Patton, Louisiana resident and senior campaigner at the Center for International Environmental Law, said that the UN experts’ statement “affirms what those of us living and working in Louisiana have known for decades: The corporate polluters that have created Cancer Alley trample on a wide range of human rights, from the right to clean air to the rights to water, life, and non-discrimination.” In an email to DeSmog, Patton added that the singling out of the Formosa Plastics mega-complex in St. James is significant. “This project is at a critical juncture in its permitting process, and we are urging our state and federal governments to heed the call from the human rights experts, and stop this plant from coming to St. James.”

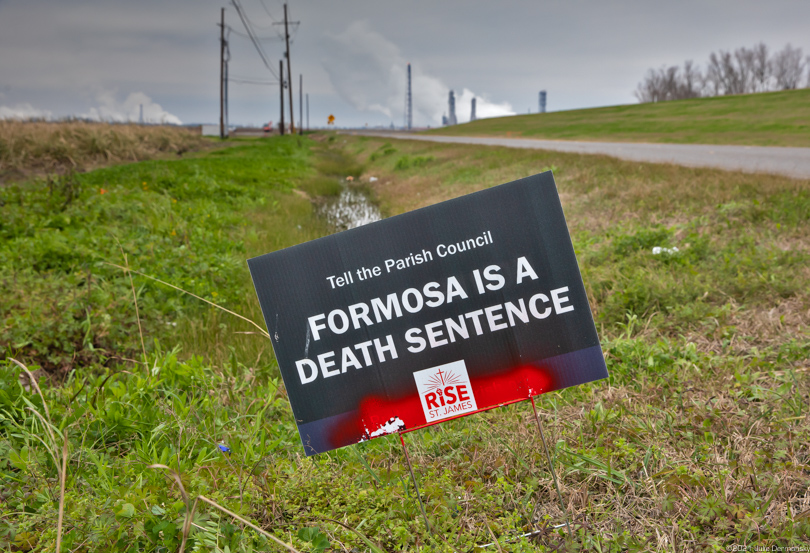

One of many signs with a message protesting against the “Sunshine Project,” Formosa’s proposed petrochemical complex in St. James, Louisiana.

A view of the Mosaic fertilizer plant on River Road in St. James, Louisiana, taken from the Sunshine Bridge.

The UN experts’ statement comes after years of campaigning and protests by Louisiana residents, community organizations, and environmental advocacy groups. In November last year, Loyola University law students, with the support of many of these same groups, sent a letter calling for intervention to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, and related intolerance.

In response to the UN statement, FG LA LLC called “protecting health, safety, and the environment” a priority for the company and emphasized that the Sunshine Project meets all regulatory criteria.

“We are constructing this project with advanced emissions reduction mechanisms in place and extensive measures to protect the environment, and also plan to keep pace with technological advances that may enable the company to further strengthen those measures,” Janile Parks, Director of Community and Government Relations for FG LA LLC, told DeSmog by email. “As the project continues forward, FG will uphold its commitment to operate safely, listen to community concerns, keep the community informed, support real needs in the parish, and continue to be a responsible corporate citizen.”

The company also said it included “the remoteness or distance from nearest residents” as an important criterion in choosing the location of the facility. Its choice of location — a former sugar plantation — has also raised concerns after an archeologist hired by a nonprofit law firm representing RISE St. James identified the gravesites of former enslaved ancestors on the property in 2019.

A home in St. James Parish near the Sunshine Bridge, which is already impacted by industrial emissions.

Cemetery in St. James, across from LOCAP oil storage tanks.

Diane Wilson, a Texas-based activist who sued Formosa Plastics Corp. USA over its plastics water pollution in her state and won, disagrees with Parks’s statement. According to Wilson, Formosa is anything but a responsible corporate citizen. Despite a $50 million settlement and agreement not to release any more plastic into waterways, Wilson continues to report instances of the company releasing the nurdles it manufactures into local waterways in Point Comfort, Texas.

In addition, Texas state regulators recently fined that same Texas plant $333,638 for air quality violations, including for the unauthorized release of carcinogens, feeding further skepticism in the mind of Wilson about the company’s claims of corporate responsibility.

Parks also pointed out that FG’s air quality permits were approved by the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, adding, “Any claim that FG will greatly increase ‘toxic emissions’ in the area is a misrepresentation and inaccurate.”

Lavigne finds this claim — that the petrochemical complex won’t further pollute the area because it received government permits — laughable. The other factories releasing pollution around her were permitted by the government too, she pointed out.

Home near oil storage tanks in St. James.

At a February 12 press conference, a Louisiana-based community coalition known as the Coalition Against Death Alley (CADA) cited federal data showing Louisiana has the highest toxic air emissions per square mile of any state. That data comes from the EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory, and the EPA’s most recent National Air Toxics Assessment (2014) showed that parts of Louisiana have high potential cancer risks.

In her response to the UN human rights statement, Parks also took issue with the region’s moniker “Cancer Alley,” a moniker that came from residents starting in the 1980s. “Simply stated, there is no scientific proof that cancer rates in the Industrial Corridor, including St. James Parish, or District 5 where The Sunshine Project is located, are higher due to industrial activity,” Parks said. “In fact, cancer rates and deaths are lower than, or there is no significant difference from, the rest of the state.” As evidence, she pointed to reports from the Louisiana Tumor Registry, which aggregates data on cancer incidences in the state.

The Zion Travelers Cemetery in Reserve, Louisiana, which is located in St. John the Baptist Parish. Next to the cemetery is the Marathon Refinery.

The Noranda Alumina plant in Gramercy, Louisiana, is permitted to release mercury into the air.

Lavigne is frustrated when she hears the state’s tumor registry data used to dismiss her community’s health concerns. She thinks that this plays into the racial inequality faced by fenceline communities in Louisiana. “To really know the cancer rate you’d have to give free cancer screenings to everyone in the community,” Lavigne said. “It isn’t like there is vigorous cancer screening here.”

The cancer registry’s findings don’t hold much weight for the people like Lavigne who are living near to oil storage tanks, which can leak methane, and petrochemical factories that release a range of air pollutants. Louisiana fenceline communities like hers are under-served when it comes to health services, she said. Dr. Chip Riggins with the Louisiana Department of Health alluded to that point when he recently acknowledged that the lack of pharmacies and health centers, particularly on the west bank of the Mississippi River, which is in the same area as the proposed Formosa complex, have complicated the COVID-19 vaccine rollout for these communities.

A member of the UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights disagreed with FG’s statement about the health risks of its project’s emissions.

“The 1.6 million pounds of toxic air pollutants to be released by Formosa’s planned petrochemical complex includes thousands of metric tons of known carcinogens, such as ethylene oxide, benzene, 1,3-butadiene, acetaldehyde and formaldehyde,” Dr. Marcos A. Orellana, who is also an adjunct professor at the George Washington University School of Law, told DeSmog. “Exposure to these hazardous substances poses a clear and grave risk to the right to life and the right to health.”

The Holy Rosary Cemetery next to the Dow Chemical Company facility near the Mississippi River in Hahnville, Louisiana.

Main image: CF Industries in St. James Parish, Louisiana, at the foot of the Sunshine Bridge. Credit: All photos by Julie Dermansky for DeSmog

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts