Martina Comparelli’s pollen allergies have been getting worse. Sometimes it’s so bad that she has to spend whole afternoons in bed with her windows closed. As the planet heats up, allergy seasons are getting longer and the climate crisis is “violating” her “right to health” said Comparelli, a climate activist in her 20s with Fridays for Future Italy.

Above all, though, Comparelli is afraid. She is afraid that when her parents are older, they will be subjected to the tremendous heat waves climate scientists say are already becoming more common. She is afraid for her own future. And her country isn’t doing anything to protect them. That is why Comparelli is suing.

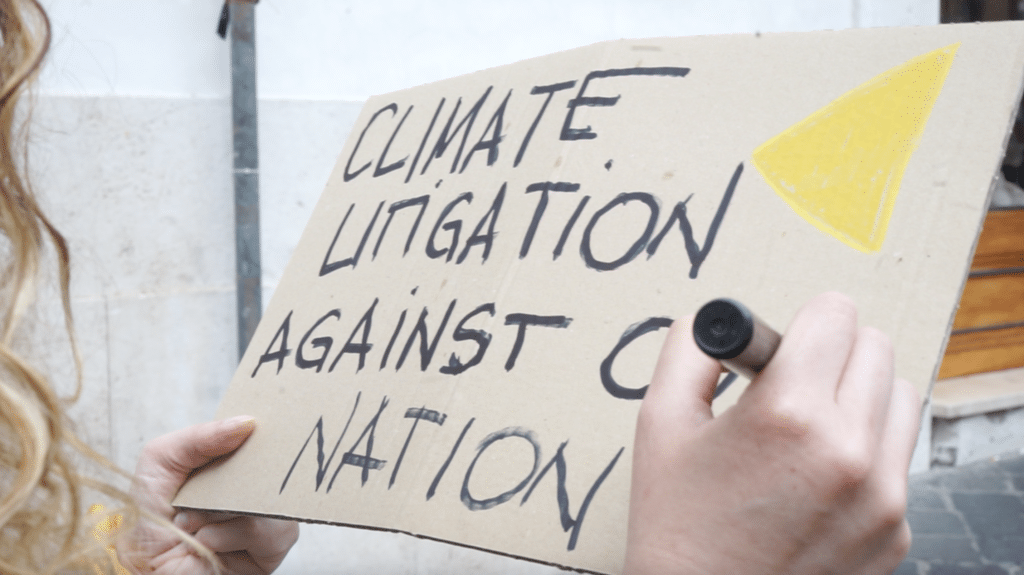

The activist is one of two hundred plaintiffs suing Italy for taking insufficient action to fight climate change. If successful, their lawsuit could spur Italy to make major cuts in climate pollution by 2030. The lawsuit, which heads to court next month, is the first climate case against Italy, and it marks a historic moment for European climate lawsuits.

“Climate litigation is a formidable tool to put pressure on the State and ask to strengthen its efforts in the climate fight,” said Marica Di Pierri, spokesperson for A Sud, the organization bringing the lawsuit. “As members of the civil society we have the duty to do everything in our power to avert a catastrophe that is just around the corner. That’s why we have decided to [bring] the first Italian climate lawsuit.”

The plaintiffs’ goal is to ask the Civil Court of Rome to declare that Italy is responsible for failing to tackle the climate emergency, and that its efforts to date are insufficient to meet the long-term temperature goal set by the Paris Agreement, which Italy ratified in 2016. Italy’s current climate plan is to reduce emissions by around 55 percent by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. But while coal is being phased-out, oil and gas remain part of the country’s energy mix.

The legal action stems from a climate-awareness campaign called Giudizio Universale (The Last Judgment) also initiated by A Sud, which has been dedicated to environmental justice and human rights issues for years.

Ahead of the first court hearing in Rome on December 14, Giudizio Universale will be travelling to the COP26 climate conference currently underway in Glasgow, Scotland, where they hope to raise awareness about their case.

Behind the lawsuit is a legal team of lawyers and university professors, who are founders of the network Legalità per il Clima (Legality for Climate). The case is represented by lawyers Luca Saltalamacchia, an expert in human and environmental rights protection; Raffaele Cesari, an expert in civil environmental law; and Michele Carducci, an expert in climate law from the University of Salento in Puglia.

In a statement, the lawyers called out the “contradiction” between the measures Italy should be taking to reach its target for limiting global warming and their “inadequate implemented actions.”

The lawsuit is “by no means symbolic”, according to the Giudizio Universale campaign website. That’s because, ultimately, the plaintiffs aim to ask the Court to order Italy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 92 percent below 1990 levels before 2030 — a major shift from the country’s current policy trajectory. According to Giudizio Universale, this emissions reduction target has scientific backing, which was submitted along with the lawsuit.

Italy’s first climate lawsuit comes during a critical year for the country, which was battered by extreme weather events. The most recent of which occurred at the end of October when Sicily – which, in August, recorded the highest temperature ever experienced in Europe – was hit by a Mediterranean hurricane, known as a “medicane”, with winds up to 120 kmph (75 mph). The medicane triggered landslides and floods, and killed at least two people.

After record heat in the summer – Floods in Sicily, Italy. This is the #climatecrisis unravelling.

— Mike Hudema (@MikeHudema) October 27, 2021

There is no planet B, no time to wait. #ActOnClimate#ClimateEmergency #ClimateAction #climate #energy #BuildBackBetter #Cop26 pic.twitter.com/lOWjgedQ93

The farmers’ association in Sicily said in a statement that on October 24 more than 300 mm (11.8 inches) of rain fell near the ancient port city of Catania in just a few hours — nearly half the average annual rainfall for the Mediterranean island. According to the European Severe Weather Database, Italy was hit by more than 1,300 extreme weather events, ranging from heavy rain and flash flooding to severe wind, in 2020 alone. This is compared to around 380 in 2010 and approximately 40 in 2000.

At the same time the medicane hit Sicily, the main public television network in Italy hosted an interview with a prominent Italian climate denier who said that human activity “has nothing to do” with climate change. Italy is one of the few countries whose media platforms – including mainstream outlets – still promote climate science denier voices, giving the public the false perception that there is uncertainty over human responsibility in the climate crisis and that the scientific debate on anthropogenic climate change is still ongoing.

This false balance in Italian media perpetuates the misleading idea that the climate crisis is not affecting Italy or the Mediterranean and that extreme weather events like those happening all over the peninsula — and which are getting more intense and frequent — are not linked to human-caused climate change.

In response to such climate science denial, Giudizio Universale’s plaintiffs also include some scientific experts such as well-known Italian climatologist Luca Mercalli, president of the Italian Meteorological Society..

“For decades the Italian State has been promising to reduce its impact on the climate, to mitigate risks, to build resilience to the consequences of global warming. But words are not matched by actions, which are always insufficient and undersized compared to the urgency,” Mercalli said in a statement. “And above all, while promising green transitions, it continues to support the most environmentally harmful practices. That is why I am suing my State.”

The Giudizio Universale lawsuit is one of many climate cases initiated by civil society in more than 40 countries around the world and “has the potential to change Italy’s climate policies for the decades to come,” said Dennis van Berkel, Urgenda Foundation lawyer and Director of the Climate Litigation Network.

The Urgenda case, filed against the Netherlands federal government, set a powerful precedent in climate litigation because it constituted the first decision by any court in the world to order a government to limit greenhouse gas emissions for reasons other than statutory mandates.

Today we call on all world leaders: let's accelerate! #climatemiles #COP26Glasgow #COP26 #ClimateAction https://t.co/Ii8f1R5JCN pic.twitter.com/Dg4CcsqTpt

— Urgenda (@urgenda) November 1, 2021

Three years after the case was filed in 2015, the Dutch Supreme Court ruled that the government had an obligation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 25 percent below 1990 levels by 2020, finding the existing pledge to reduce emissions by 17 percent was insufficient to meet the country’s contribution toward the Paris Agreement goal. According to the Dutch court’s ruling, failure to comply with this limit is a violation of Articles 2 and 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which protect people’s right to life and well-being.

It is no coincidence that a major platform of these lawsuits posits that climate actions are, above all, closely related to human rights. In the case of Giudizio Universale, for example, what is at issue is whether Italy is violating its citizens’ fundamental rights through its inaction on the climate emergency.

The lack of adequate climate action at both the international and domestic level, even in the face of overwhelming scientific evidence, is considered one of the greatest intergenerational human rights violations, says the Giudizio Universale campaign. “Climate inaction results in violation of fundamental rights, the right to life, health, water, food, housing and shelter, and it is necessary to recognize stable and safe climate rights as a framework that guarantees the full enjoyment of other rights,” said Di Pierri, with A Sud.

Taken together, climate lawsuits around the world are a growing legal trend pushing for more concrete, global climate action on multiple fronts — not just legally but also politically and policy-wise as well as on the economy and social justice fronts.

According to the website climatecasechart.com, which provides two databases of climate change lawsuits, there are currently 1,390 cases in the United States and 441 cases in the rest of the world. Last month, the environmental organizations Notre Affaire à Tous, Fondation Nicolas Hulot, Greenpeace France, and Oxfam France won a 2019 lawsuit against the French state in which the government was found responsible for ill-managing the climate crisis. As a result, France will have to cut 15 million tons of carbon by the end of 2022 to repair the damage caused by the overrun in emissions between 2015 and 2018.

[BILAN AFFAIRE DU SIÈCLE] ⚖️

— Notre Affaire à Tous (@NotreAffaire) November 3, 2021

🔴💥 Le 14 octobre, l'État a été condamné à réparer le préjudice écologique causé par son inaction climatique.

🤔 Que va changer cette décision ? On répond à toutes vos questions ! ⬇ pic.twitter.com/hZLeJy5KkW

“This was a historic victory: the French state will be forced to double its reduction efforts in the coming year. If it doesn’t, a request to the court for a financial penalty is already on the table,” said Cécilia Rinaudo, executive director of Notre Affaire à Tous.

The French climate victory adds to those already won in Germany, Netherlands, and Belgium where other activists and environmentalists have forced countries to increase their emissions reduction targets. In Germany, where the targets are much higher than those of Italy, a recent court ruling deemed inadequate those targets to the point that they represent a violation of the rights of future generations.

Recent research published in the journal Science has shown that people born today will suffer many times more extreme heatwaves and other climate disasters over their lifetimes compared to their grandparents. Young people are increasingly exposed to the effects of an altered climate and they feel the severity and urgency of the crisis. In fact, Giudizio Universale has 17 plaintiffs who are minors.

Climate litigation’s role in requiring states and companies to intervene in the fight against climate change is increasingly essential as they otherwise appear slow to ramp up actions and ambitions outside of court. But as Martina Comparelli points out, this approach is especially pivotal to recognizing human rights, the rights of future generations, and social justice in climate action at the national and international levels.

“My State,” Comparelli said, “is condemning my future, that of other young people and that of future generations.” said.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts