Oil and gas investors are anticipating hefty dividend checks to close out 2021. Following a decade of red ink — capped by a devastating 2020 when oil prices briefly went negative — fracking-focused companies finally made some money this year. High energy prices and a slower pace of drilling allowed North America’s shale firms to harvest a bumper crop of cash through the summer and fall. They’re now returning much of that bounty to investors, rather than just plowing it back into new wells.

Yet a new analysis from earth scientist David Hughes, writing for the nonprofit Post Carbon Institute, suggests that the industry’s future may not be nearly so bright.

Each year, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecasts production from the nation’s tight oil and gas plays — the hydrocarbon-rich formations targeted by the U.S. fracking industry. And each year, the EIA predicts rosy prospects for the nation’s oil and gas output.

In its 2021 outlook, for example, the agency predicted that tight oil production would rise by 12 percent through 2050, while shale gas yields would rise by 27 percent. In the EIA’s view, the nation’s shale industry is awash in oil and gas, and the fracking boom is poised to thrive for decades to come.

But Hughes carefully peered through the EIA’s forecasts, basin by basin, comparing the agency’s assumptions against the real-world drilling data that showed faltering productivity and fast declines from many shale wells. And he concluded that the EIA’s long-term oil and gas outlook suffers from an optimism bias so extreme that it borders on fibbing.

A Closer Look at the Bakken

It’s not just one basin, or a few, that are out of whack. Hughes examined 13 shale drilling regions in the U.S., and concluded that three of the EIA’s forecasts were extremely optimistic, while five were highly optimistic. The remaining five were only moderately optimistic. All told, Hughes concludes that the long-term production outlook for the U.S. shale industry is almost certainly far below the EIA’s overly rosy projections.

Take, for example, the Bakken Shale, the cradle of the nation’s oil fracking boom. Bakken oil output in Montana and the Dakotas had begun to falter even before COVID-19 sucked the wind out of the global economy. Still, the pandemic hit the Bakken hard: From the peak in late 2019 to July 2021, oil production in the region fell about 25 percent. It shows little signs of recovery.

Yet the EIA forecasts that the region’s oil output will rise quickly, topping 1.6 million barrels per day within three years. That’s half a million barrels per day higher than it is today. And the agency suggests Bakken output will plateau at roughly that level for two and a half decades.

Hughes is skeptical, to put it mildly. He points to data showing that Bakken oil and gas is concentrated in a few highly productive regions, where underground shale layers trap an abundance of hydrocarbons. Drillers have steadily migrated to these “sweet spots,” and drilling outside the core has come to a virtual standstill.

But the sweet spots are being tapped out. Over-drilling just makes wells produce less oil and gas, so drillers will have no choice but to move to less productive acreage over time. And since output from a typical Bakken well drops about 90 percent within the first three years, the industry will have to drill more and more mediocre wells just to keep overall output stable.

This sets up a Red Queen’s race, with drillers running faster and faster just to stay in place. In this new report, Hughes estimates that the industry would need to drill another 69,400 wells in the Bakken to sustain the EIA’s projected output. That’s on top of the nearly 17,000 wells drilled there to date. To meet that level of production, the fracking industry would burn through roughly $541 billion in capital (in today’s dollars) between now and 2050.

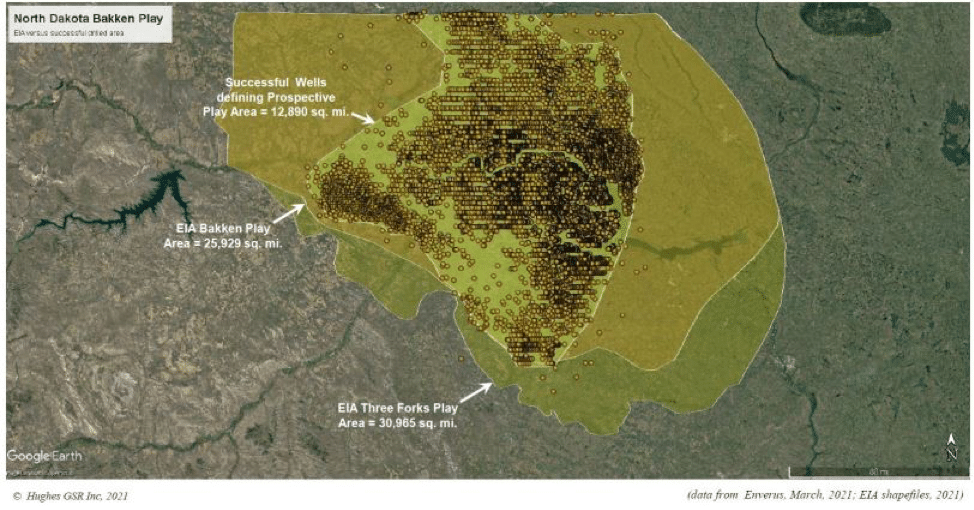

What’s worse, the EIA may be overestimating the number of viable drilling spots left in the Bakken. So far, Bakken drillers have successfully drilled in a region encompassing about 13,000 square miles.

But the EIA defines the Bakken Play at nearly 26,000 square miles. If there were abundant oil outside Bakken’s core, the industry would probably have found it by now. Yet in its forecasting, the EIA seems to assume that areas up until now shunned by the industry will still yield a bounty of oil and gas.

The EIA’s Biases

In basin after basin, Hughes points to at least three factors that systematically bias the EIA’s forecasts in favor of more oil and gas production. First, the agency overstates drillable acreage, in some cases dramatically, which boosts its estimates of “unproved technically recoverable resources” — jargon for oil that the industry isn’t sure is there.

Second, the EIA seems to assume that wells can be packed more closely together than the industry finds wise; drilling cheek-by-jowl is a recipe for disappointing results.

Third, the EIA seems oblivious to diminishing returns: Better drilling and fracking techniques simply can’t outpace the exhaustion of high-quality drilling sites. In fact, in many parts of shale country, Hughes finds that output from new wells has already stagnated or declined.

Not factored at all in the EIA’s analysis are the rising volumes of water and chemicals that the industry has had to use to coax more oil out of the ground. In the Bakken, for instance, water injection per well increased 370 percent between 2012 and 2018. Increased water demand for hydraulic fracturing — in order to access ever more meager reserves — will lead to higher costs and worse returns for oil producers. Water scarcity could make some wells not worth drilling.

The EIA’s forecasts matter. They are often viewed as the government’s official projection of the U.S. oil and gas industry’s future. The agency’s announcements have an aura of credibility. Policymakers, investors, oil traders, and industry analysts pay close attention to what the EIA says.

So when the EIA claims that the fracking boom has no end in sight, it encourages more investment in oil and gas, while discouraging investment in alternatives. This delays the transition to renewables, even as it sets up consumers for more dramatic price shocks and supply disruptions if oil and gas output falls short of expectations.

Hughes’s report should be a wakeup call to the agency to thoroughly reevaluate its forecasts. And it should be a glaring warning to investors: they may be enjoying this year’s dividends, but if Hughes is correct, they might not last for long.

Clark Williams-Derry is an Energy Finance Analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts