This story is part of a collaboration between DeSmog and Public Health Watch.

“The normal flare plus the BBQ is on,” Elida Castillo, the program director of Chispa Texas, an environmental advocacy group, wrote to me in a text on December 6. It was an update about a new, giant plastics plant built on the line between two small Texas cities just northeast of Corpus Christi: Portland and Gregory.

Castillo clarified that the “barbecue” was a ground flare at the $10 billion manufacturing complex — a joint venture between ExxonMobil and Saudi Basic Industries Corporation (SABIC) known as Gulf Coast Growth Ventures (GCGV). The site is home to the world’s largest ethane steam cracker plant, which will feed the production of nurdles – tiny pellets that form the building blocks for plastic products.

The burning of the ground flare is a sign production could begin soon. I asked GCGV if production had begun and if not, when it would, but did not get a response.

A video on the GCGV website explains that ground flares are used to burn off leftover gas from the production process.

A certain amount of flaring is permitted and expected when petrochemical plants and refineries start up or go offline. Flaring at other times is a sign of an ‘upset’ — industry’s term for a problem resulting in unplanned emissions. And according to ExxonMobill, “Excess hydrocarbon gases are burnt in the flare systems in an environmentally sound manner, as an alternative to releasing the vapour directly into the atmosphere.”

The ground flare at the Exxon-SABIC plant lit up the sky and was visible for miles. It alarmed many who hadn’t seen warnings posted on social media or gotten an email alert from the facility. The email said the ground flare “will create a glowing effect near ground level and produce a rumbling sound.”

The GCGV video offers assurance that its ground flare is nothing to worry about. The flare allows the plant to use multiple smaller burners, “similar to a giant barbecue and much like your barbecue there’s a great pop when it ignites. The multiple burners do a better job of combustion when compared to a traditional flare tower,” the video says. And the plant’s fact sheet claims its ground flare “is designed for safety and to minimize impacts to the community.” But the flare in the video is much smaller than the one that lit up the sky on December 6.

I arrived in Portland that night after driving from south Louisiana, documenting some of the fossil fuel industry’s expansion in the Gulf Coast region along the way. New liquefied natural gas (LNG) and oil export facilities are springing up, as well as petrochemical plants like the GCGV ethane cracker. Despite warnings from climate scientists, this buildout reflects movement away from the 2015 Paris agreement’s goal of limiting greenhouse emissions to keep warming to below 2°C.

“It is like Dante’s Inferno, not a barbecue as promised,” a resident who lives close to the plant told me as we watched the ground flare. Massive, smelly flames rose above the flare’s protective walls and made a loud hissing noise.

“Comparing a ground flare to a barbecue is absurd,” Wilma Subra, an environmental scientist and a community advocate in New Iberia, Louisiana, said in a telephone interview.

There are generally two types of flares at petrochemical manufacturing facilities: elevated flares, also known as tower flares, where an open flame is seen at the top of a stack, and ground flares, made up of many small burners low to the ground behind a protective shield meant to block light and sound. The industry claims ground flares can be cleaner than tower flares.

“Whether a petrochemical plant uses the tower flare or the ground fare or a combination of both … it’s going to be spread out close to the workers on the ground and the community around it,” Subra told me. Such flaring can release carcinogens such as benzene and vinyl chloride, she said.

Encarnacion Serna, a chemical engineer who lives 3 miles from the GCGV site, agrees with Subra. “It doesn’t matter if it is a tower or a ground flare, the chemistry is the same,” Serna said.

He pointed out that fencing doesn’t stop the pollution. “The reason they burn it low to the ground is less people can see it,” he said.

Hiding the flare also does nothing to stop greenhouse-gas emissions. According to its air-quality permit, the Exxon-SABIC plant is allowed to emit about 3 million tons of carbon dioxide a year into the atmosphere. It joins another 31 new oil, gas, and petrochemical projects along the Texas and Louisiana coasts that will add another 50 million tons of greenhouse-gas pollution – the equivalent of 11 new coal-fired power plants, according to a report by the Environmental Integrity Project, a nonprofit research and advocacy organization.

Subra finds the ground flares I photographed in Texas and Louisiana worrisome. Their large scale and proximity to the ground likely increase the potential impact to those around them if there is an upset resulting in an increase of emissions. With tower flares, emissions are released high into the atmosphere, with a ground flare, emissions have less chance of dissipating before they could be inhaled. If the flare’s pilot light goes out, more gas and other chemicals will be released unburned, leading to higher emissions.

The chances of this happening are low but could increase due to climate change. As the planet warms, hurricanes are intensifying more quickly, leaving less time for facilities to shut down before they are potentially hit. This can result in large pollution events – with the release of more greenhouse gasses and toxic emissions, further contributing to global warming.

When Hurricane Harvey hit the industrial corridor around Houston in 2017, for example, releases from petrochemical plants and oil refineries blackened the skies near some of the facilities. The same thing happened in Westlake, Louisiana, after Hurricane Laura hit in 2020, and along the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, in the region known as Cancer Alley, following Hurricane Ida this year.

Horses grazing in Gregory, Texas, near the Exxon-SABIC plant. Credit: Julie Dermansky Homes in Portland, Texas, that have a view of the Exxon-SABIC plant Credit: Julie Dermansky

The Exxon-SABIC plant is ominous even without its ground flare visible. It dominates the landscape — built in the middle of ranchland and cotton fields punctuated with towering wind turbines, it is visible for miles in every direction.

About five miles northwest of the ethane cracker plant is Taft, a small town where Castillo’s family has lived for generations. She returned from San Antonio about a year ago.

“I’m a daughter of the Coastal Bend [the area along the coast from Aransas Bay to Corpus Christi] and I love my community,” she told me on a windy morning as we drove around Taft. “I love the people that I have grown up with and I want to preserve this area for my nieces and nephews and for all those who are coming after us.”

She doesn’t think it’s fair that she, and generations that came before, were able to enjoy the area’s natural beauty only to leave a polluted wasteland for their children. She is working with the Coastal Alliance to Protect our Environment, known as CAPE — a coalition formed in 2018 to stop the further industrialization of the area. It includes local groups such as Portland Citizens United and Indigenous People of the Coastal Bend, as well as statewide and national organizations like Earthworks and Texas Campaign for the Environment.

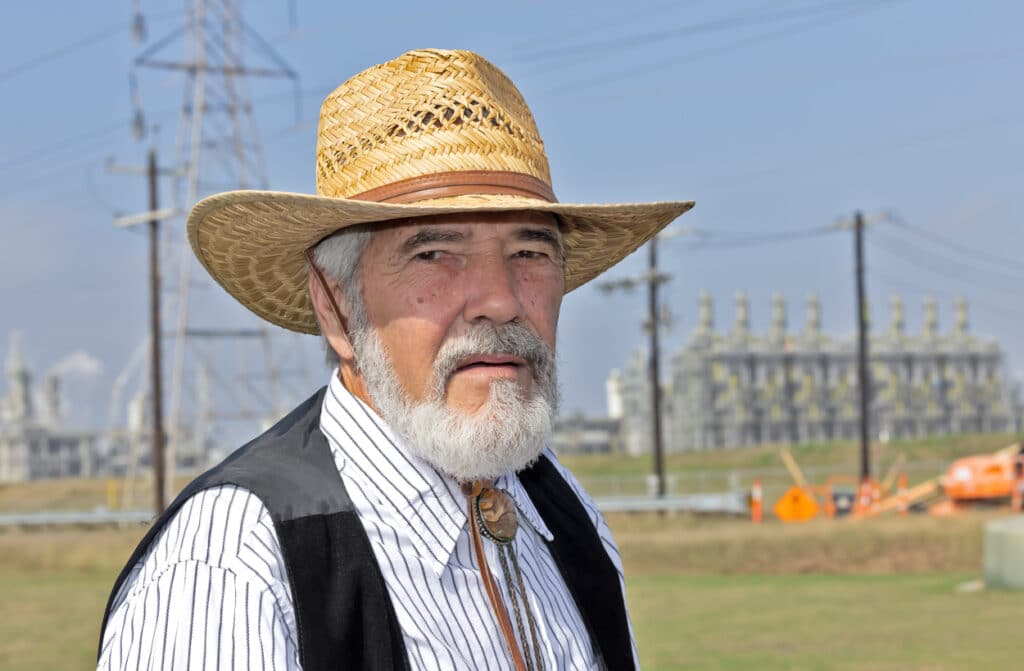

Errol Summerlin, the founder of Portland Citizens United, is a retired Legal Aid attorney whose home is about two and a half miles away from the Exxon-SABIC plant in Portland. He told me the toxic brew the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality has allowed the plant to emit is “not necessarily what they’ll put out. They could put out more.”

Summerlin said the region, once sparsely populated, was transformed into an industrial mecca about seven years ago, as oil and gas from the Permian Basin and Eagle Ford Shale began flowing in increasing quantities into the Corpus Christi area.

Summerlin doesn’t plan to leave Portland for now, though the occasional shaking of his house from the Exxon-SABIC plant startup makes him wonder how safe he would be if he stayed.

View of Corpus Christi from the Nueces Bay Causeway. Credit: Julie Dermansky A “Welcome to Corpus Christi” message on an oil storage tank. Credit: Julie Dermansky

Corpus Christi, just across the Nueces Bay Causeway from Portland, has long been known for air pollution from Refinery Row, a 10-mile-long industrial stretch northwest of downtown. The bad air drifts into Taft, where Castillo’s mother died from congestive heart failure and respiratory failure, illnesses associated with long-term chemical exposures.

“I don’t want others to experience that,” Castillo said. Most in Taft associate industry only with jobs, not health problems. “What they do know,” Castillo said, “is that Gulf Coast Growth Ventures donates a lot of money to the police and fire department and sponsors things like neighborhood cleanups.” This, she believes, helped tamp down opposition to the ethane cracker.

On its website, GCGV says the ethane cracker will generate “$50+ billion in economic gains” for the state during its first six years of operation.

Castillo thinks more members of the community might have fought the plant if they’d had a better understanding of what it would bring when operational — increased noise pollution from train and truck traffic, hazardous air emissions, depletion of the local water supply (it will use 20 million gallons of fresh water a day. )

We stopped by the home of Castillo’s uncle, Jose G. Garcia, who has a clear view of the hulking cracker from three miles away. Garcia, an 85-year-old Air Force veteran, said he welcomes the jobs and money GCGV is spreading around the community but worries about the plant’s health impacts. He said he’s taking a “wait-and-see” approach.

On my drive back to Louisiana I recognized a familiar glow as I approached Westlake, just east of the Texas state line. What appeared to be a giant ground flare illuminated the sky for miles. I got off Interstate 10 to investigate and followed the light to Sasol’s chemical plant.

I asked Sasol what caused the flare but didn’t get a response. Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality spokesperson Greg Langley told me the flare was a result of the plant going back online after it had been shut down for maintenance. Such flaring is allowed, Langley said, though it results in the release of limited amounts of particulate matter, volatile organic compounds, sulfur dioxide, nitrous oxide, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide. These substances have been linked to cancer, respiratory illness and other conditions.

Ground flare at the Exxon-SABIC GCGV plant on December 6, 2021 seen from a residential neighborhood in Portland, Texas. Credit: Julie Dermansky Ground flare at Sasol’s Lake Charles petrochemicals complex in Westlake, Louisiana, on December 10, 2021. Credit: Julie Dermansky

I asked Subra if she could tell from my photos of the Exxon-SABIC ground flare and the Sasol ground flare whether toxic chemicals had been released. “Absolutely,” she said.

I asked GCGV and Sasol whether they monitored the air for such chemicals. Neither responded in time for publication.

CORRECTION (1/26/22): The original version of this article stated that the GCGV facility is among the 31 new oil, gas, and petrochemical projects along the Texas and Louisiana coasts included in an EPI report. That has been corrected.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts