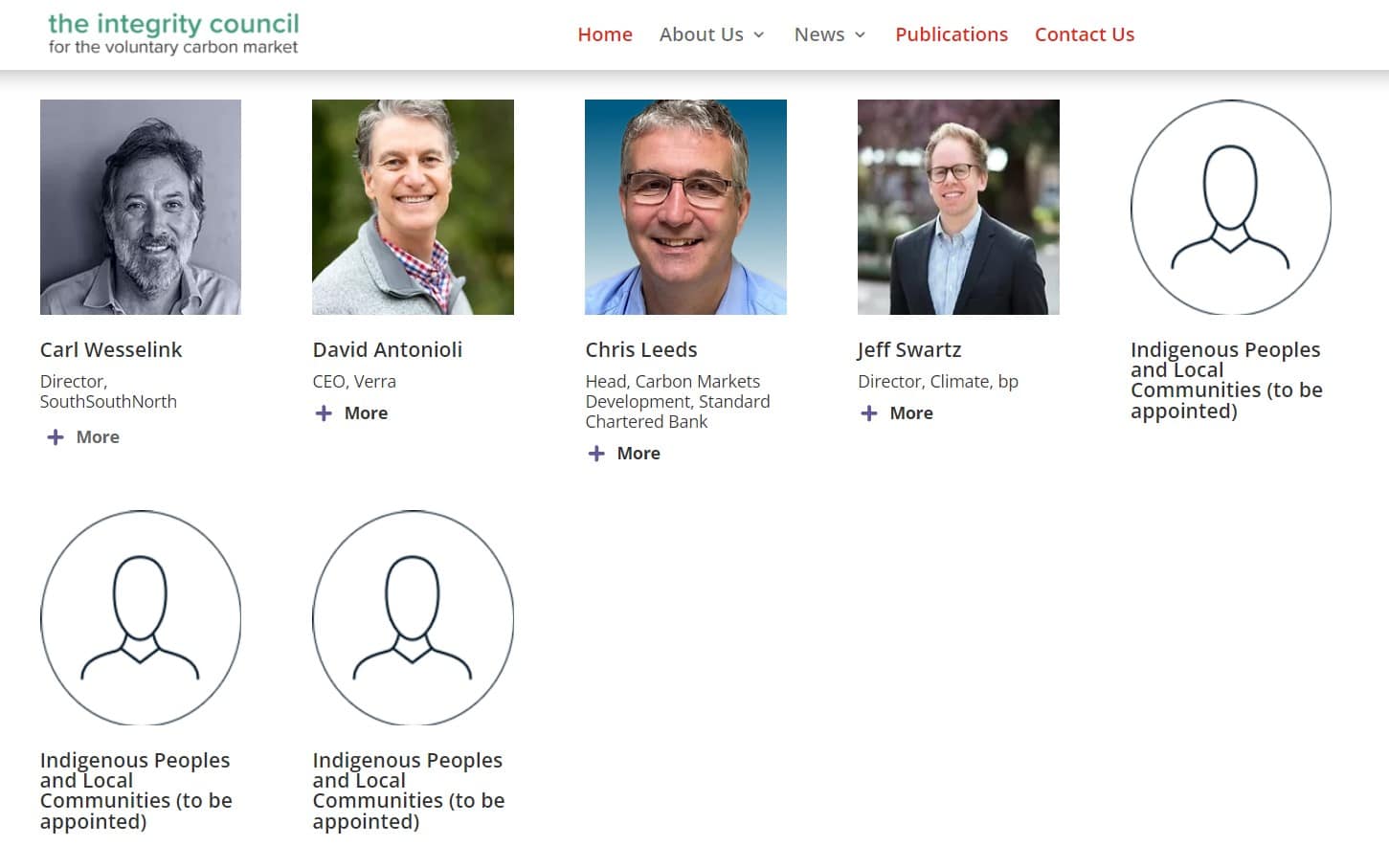

A new governance body set up to regulate how private companies offset carbon emissions has failed to appoint Indigenous board members months after pledging to do so, amid ongoing concerns over representation in the carbon marketplace.

The Integrity Council for Voluntary Carbon Markets (IC-VCM), which launched last year, has acknowledged it is “essential” to represent the communities that are home to the majority of “nature-based projects”, which carbon trading relies on.

But nearly five months after it announced the first 19 members of the board — who include a senior executive from oil company BP — the Council has still not filled the three posts set aside for Indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLC), with campaigners labelling attempts at outreach as “desperate”.

The body is due to finalise key principles on how the integrity of carbon credits will be ensured in the coming months, but carbon trading platforms are already being launched — without robust principles in place. Last week a forest carbon marketplace raised $50 million in finance to help form “new natural capital markets”.

Concerns over representation come after critics accused the voluntary carbon markets taskforce led by former Bank Of England governor, Mark Carney, of appointing “vested interests” such as oil majors, banks and airlines to design the market’s rules.

The new body — which was set up by the taskforce in September — is tasked with “ensuring the integrity” of the voluntary carbon markets. But Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN) campaigner Joye Braun, from the Cheyenne River Sioux tribe, is doubtful the body can successfully hold polluters to account.

“The Council lacks teeth,” Braun told DeSmog. “If you have a corporation using the market, let’s say Exxon or Shell or BP or any of those companies, their main concern is the bottom line. They want money and they will continue to do what they do.”

Carbon Markets

Indigenous peoples are disproportionately impacted by carbon markets. They make up just five percent of the global population, but protect at least 20 percent of natural ecosystems and 80 percent of the world’s biodiversity. The wetlands and forested areas in their territories are home to the carbon stocks that form the basis of emissions trading.

Despite the crucial role they play in climate protection, Indigenous communities are regularly excluded from international decision-making processes around carbon markets.

This was evident in the creation of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which laid out a market-based framework to reduce greenhouse gas emissions through trading carbon credits to meet national climate targets, without consulting Indigenous peoples. Governments with individual climate targets could “offset” by buying or selling carbon credits, in theory avoiding or removing the equivalent greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.

However, the system was widely considered to be open to abuse and to fail in its goal of reducing emissions. In one key UN scheme, three quarters of its allowances were found to lack environmental integrity — according to a major report in Nature. Many projects were found to lack “additionality”, meaning carbon savings would have happened anyway and, in some cases, may not have existed at all.

Indigenous communities, who have contributed least to the harmful emissions driving climate change, have also been impacted by land grabs from the creation of some carbon-credit projects.

At the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, nearly 200 governments finally agreed on rules for the long-debated carbon markets “playbook”, Article 6, which was intended to help avoid issues such as double counting and cut a fairer deal for IPLC communities. However, a number of Indigenous groups described the Glasgow Climate Pact as a “death sentence”, due to the new rules allowing the carbon markets to scale up dramatically.

In addition to compliance markets used by governments to meet climate targets, voluntary markets are increasingly used by individuals and businesses to offset emissions outside of mandatory schemes. The taskforce has estimated the market could grow by a factor of 160 by 2050, as companies come under increasing pressure to offset their carbon emissions to deliver on net-zero targets.

Top of the Integrity Council’s to-do list is defining the Core Carbon Principles (CCPs), which would verify carbon credits and try to ensure they bring real social and environmental impact to communities as well as reduce overall global carbon emissions.

But with the CCPs due to be completed later this year and with no IPLC representatives in place, time is once again running out for Indigenous communities to shape or participate in the process meaningfully.

‘Endorse and Champion’

The IC-VCM has said it is working with a number of global Indigenous groups and NGOs in order to appoint Indigenous representatives fairly.

They include supporters of carbon markets, such as Carbonext, a carbon credit developer which aims to “preserve and protect the Amazon Rainforest through Nature Based Solutions”, and Conservation International, a major U.S. conservation NGO and one of the board’s funders.

The Integrity Council has also tried to reach out to organisations staunchly opposed to carbon offsets, and recently contacted the Global Forest Coalition (GFC), a network of NGOs and Indigenous groups. The organisation — which describes carbon offsets as a “false climate solution” — was asked to “identify distinguished IPLC members” who would “support the mission of the Integrity Council” and “endorse and champion” its output.

“I guess they might be a bit desperate and didn’t do their homework,” Coraina de la Plaza, a campaigner from GFC, told DeSmog, adding that GFC declined the offer.

Braun said it was highly possible that the Council would eventually find Indigenous representatives willing to join the board, but feared any new members would run the risk of social exclusion.

“Any Indigenous person that goes on that board is going to get roasted,” Braun told DeSmog. “There’ll be some tribes that agree with these carbon markets but they don’t speak for all of us. Part of the problem is that you’re dealing with Indigenous nations, right? They’re delving into this whole snake bed of Indigenous rights and treaties.”

“As Indigenous people we see the exploitation, and that could be why we don’t have three people on the board. We’re becoming a little more savvy about that.”

‘The Jury’s Still Out’

The IC-VCM appears to have responded to concerns about the make-up of the taskforce by speaking out explicitly on representation.

The Council has stated that particular attention was paid to ensuring at least 40 percent of the body’s representatives were from the Global South, “given that an important element of high-quality, high-integrity voluntary carbon markets is the movement of private capital to the Global South, where the majority of impactful nature-based projects are located”.

However, while there is some geographical and professional diversity on the board, only carbon-market advocates appear to have been appointed so far, including major polluters who have a clear interest in helping shape a burgeoning voluntary carbon market.

Jeff Swartz, BP’s director of climate strategy and sustainability, takes up one of the three “market representative” seats on the board. BP, which is responsible for at least 34 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, has actively pursued forest-based carbon offsets over the past decade. The Institute of International Finance (IIF), which sponsors the taskforce, is also represented through U.S. managing director Sonja Gibbs.

“The significant industry presence within the IC-VCM board does raise questions and it will be important that any Indigenous and civil society organisation voices have real weight,” said Gilles Dufrasne, policy officer at Carbon Market Watch.

Core Carbon Principles are due to be launched as “a global benchmark for carbon credit quality”, but critics are not clear if they can avoid the same pitfalls of double counting, human rights abuses, and low carbon prices that have plagued the industry so far.

“The jury is still out on whether the IC-VCM will have a positive impact on the market or not. It could set a new bar for quality, or it could also provide an extra layer of meaningless approval for carbon credits,” Dufrasne said. “A lot depends on how good the final adopted quality criteria will be, and how stringently these will be applied.

“I think including more Indigenous peoples’ voices is always welcome, though of course these should be truly included, and not just used as a token presence to legitimise the rest of the initiative.”

Roshan Krishnan, climate finance campaigner at Amazon Watch, stressed that there was no single Indigenous approach to voluntary carbon markets, which he said ranged from “flat-out rejection to engagement”.

“I won’t speculate on whether the IC-VCM’s attempts at Indigenous outreach are genuine or not, but I will say that the common thread is that any carbon mitigation policies must be fully subordinate to Indigenous land rights, and provide accessible avenues for Indigenous communities to participate, taking into account language and technology differences,” he said.

“If outreach is failing, it is fair to ask whether those conditions are being met.”

A spokesperson for the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market said the body was “absolutely committed to including the expertise and voices of IPLC communities”.

“It takes time to ensure we are selecting Board members that bring the necessary diversity of knowledge and experience to represent the IPLC community globally,” they said in a statement. “We have received expressions of interest in the positions reserved for IPLC communities and are in discussions with candidates and related organizations. We expect it will take several more months to make these appointments.”

The spokesperson said the council planned to publish the Core Carbon Principles in the third quarter, “following a full and open public consultation in Q2, when all those interested in the voluntary carbon market, including representatives of IPLC communities, will be encouraged to participate”.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts