As Bill Torbett and his colleagues went about their work, handling the sloppy radioactive detritus of oilfields in a cavernous building in eastern Ohio, their skin and clothing often became smothered in sludge. Waste was splattered on the floor and walls, even around the electrical panels. At the end of their shifts, they typically left their uniforms in the company washing machine, which didn’t always work, and left their sludge-caked boots and hard hats in the company locker room. But when the men arrived home after a long day, the job came with them too.

“We were literally ankle-deep in sludge and a lot of times knee-deep in different spots. All that shit is dripping down on you,” says Torbett, a 51-year-old former employee of Austin Master Services, a radioactive oilfield waste facility in Martins Ferry, Ohio. “You’re saturated in it, your hands are covered in it, the denim of your uniform would hold it, and the moisture would soak right through your under-clothes and into your skin.”

“How wet?” Torbett says. “Like if you got caught outside in the rain without an umbrella. Soaking wet.”

In fact, so alarming are the conditions at Austin Master and so lax is the oversight that workers have taken things into their own hands. In one case, a second former worker has covertly passed along their dirty boots, hard hat, and headlamp for independent radiological analysis. The levels of the radioactive element radium found in the sludge on this worker’s boots was about 15 times federal cleanup limits for the nation’s worst toxic waste sites.

And yet, Austin Master appeared to keep workers in the dark about what they were handling. “They really didn’t tell me the gist of the material, I just knew it came from frack sites,” according to Torbett, who worked at the facility from November 2021 to February 2022. “There was no discussion of the material and its radioactivity.”

In April, DeSmog revealed that Concerned Ohio River Residents, a local advocacy group, had documented elevated levels of radium outside the main entrance to the Austin Master facility, that state inspection reports showed a lengthy history of concerning operating practices, and that rail cars leaving the facility for a radioactive waste disposal site in the Utah desert had arrived leaking on five occasions.

The situation at the Ohio facility appears so severe that top officials from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Region 5, which covers much of the Midwest, joined local organizers in a conference call in July and made an in-person visit to the area earlier this month.

The state of Ohio has authorized Austin Master Services to receive 120 million pounds of radioactive oilfield waste at its Martins Ferry location each year.

Austin Master has not replied to questions regarding the reported radioactivity levels on worker clothing. “There is nothing unusual or harmful about AMS’s process,” Chris Martin, a company spokesperson, told DeSmog in response to questions sent in March regarding work practices at the facility. “Austin Master Services takes a responsible approach to providing valuable waste remediation services and jobs in the Martins Ferry community.” Martin maintained that “there are no known complaints from AMS employees concerning work conditions.”

On July 1, American Energy Partners, a Pennsylvania-based energy and infrastructure services company, acquired Austin Master Services. In a press release, American Energy Partners describes Austin Master as “a full-service, comprehensive environmental services firm specializing in radiological waste management solutions” that provides “professional safety, industrial hygiene and health physics services.” The company has not replied to questions.

The conditions documented by state inspection reports and the contamination revealed by advocacy groups raise questions about the risks to first responders and the community should the Martins Ferry facility have an accident.

“I have dealt with chlorine gas leaks, acid leaks, oil and fuel spills, and much more, and all have had an element of containability and the ability to off-gas, neutralize, or absorb, but radium contamination is a whole different issue,” says former Youngstown, Ohio battalion fire chief, Silverio Caggiano. He has been closely monitoring the Austin Master facility with Ohio advocacy groups and has decades of experience training firefighters on the dangers of hazardous and radioactive materials.

“There is no good emergency scenario here,” Caggiano says. He offered predictions about what dangers might arise at the facility. “Given their poor industrial hygiene practices that we have photographic evidence of, even a medical situation could expose first responders to high levels of radiation and contaminate their rig as well as the emergency department. If they have a flood — that is highly probable given their proximity to the Ohio River and current weather extremes — it would spread the radium contamination everywhere, including Martins Ferry’s aquifer. If they had a fire, fighting it with water would be like a flood spreading contamination beyond any containment. If they let it burn, the smoke would carry the radioactive contaminant everywhere in the wind and any responding companies and mutual aid companies would become contaminated.”

“In my opinion, the best way to prepare for this type of business,” he added, “is to keep them out of a community in the first place.”

Welcome to the Messy World of Radioactive Oilfield Waste

The Austin Master facility is located in a former steel mill on the Ohio River, not far from the city of Martins Ferry’s drinking water wells and the football stadium of the local high school team, the Purple Riders. Austin Master receives truckloads of drill cuttings bored out of the Marcellus and Utica shale and of radioactive sludge that forms at the bottom of tanks and trucks that hold toxic liquids brought to the surface of fracked oil and gas wells. Right now, more than a third of America’s natural gas supply comes from wells in Ohio, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania. Some of it is converted to liquefied natural gas, or LNG, and shipped overseas to customers in Europe and elsewhere.

Processing radioactive oilfield waste has proven enormously problematic for the oil and gas industry and its regulators, and given rise to a booming service sector of facilities like those run by Austin Master that collect, treat, and process the waste. Part of the problem is that a significant amount of oilfield waste is too radioactive to be shipped directly to traditional landfills. Instead, it must be “down-blended,” or mixed with material like lime or a corn cob base to lower the radioactive signature. The Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) does regulate the state’s roughly two dozen oilfield waste processing facilities, but in a limited way. In 2014, Austin Master received an ODNR order, known as a Chief’s Order, giving the company temporary approval to “process, recycle, and treat brine” and other oilfield waste.

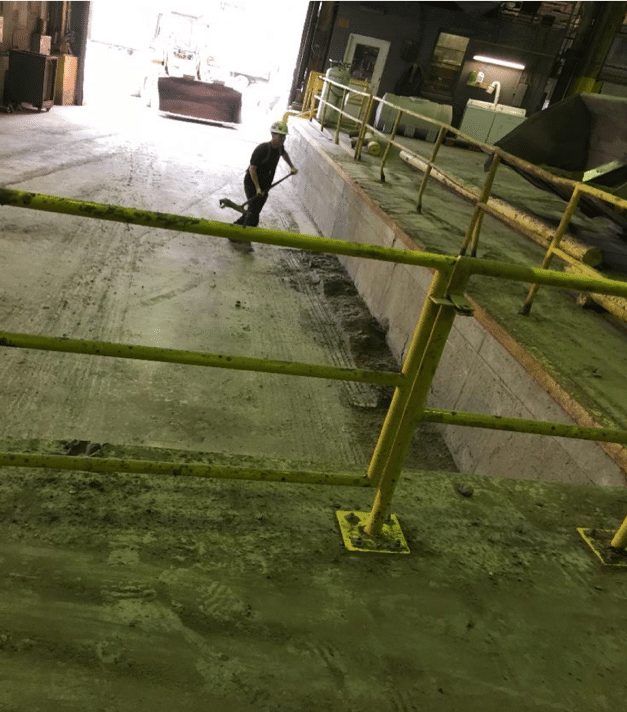

At Austin Master’s Martins Ferry facility, Torbett says, trucks regularly dumped the more sludge-like or solid radioactive oilfield waste directly onto the floor of the former steel mill, and workers used common heavy construction equipment like Bobcats to maneuver it into various bins or pits. Waste that was more liquid-like was often dumped into metal containers called half-rounds, says Torbett. In one state inspection photo from August 2018, a worker with bare arms and no face protection or respirator holds a push broom.

“The shop was a mess, sludge was everywhere — everywhere,” says Torbett. “There was a lot of cleaning and hosing down” of equipment, including a press used to solidify sludge and remove excess water, and sections of the facility used to hold waste, such as one area Torbett refers to as “the snake pit.” “Waste would just splash up on you,” he says. “And if you are running the press, you’re constantly disconnecting lines and sometimes it would squirt out.”

It is work like this that has Massachusetts-based nuclear forensics scientist Dr. Marco Kaltofen deeply concerned about worker health risks. He said any time oilfield waste is moved around in piles at a processing facility such as Austin Master, dust is inevitably created and is likely to contain the radioactive element radium, which is commonly found in oilfield waste.

In addition to dust and wet spatter from the facility’s waste processing practices, Kaltofen voiced worries about the risk of radioactivity exposure to the people interacting with employees outside of work. “Workers’ skin can also become coated with this radioactive material, and either absorb it, or contaminate their families,” he added.

Earlier this year, a second former employee of Austin Master, who prefers to remain anonymous because they still work in the region, provided the boots, hard hat, and headlamp they used while working at the Martins Ferry facility to the organization Concerned Ohio River Residents, members of which have been previously instructed by Kaltofen in how to safely handle such items. The group then sent the worker items along to Kaltofen, who sent sludge from the boots to Eberline Analytical, a radiological analysis lab in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

The lab returned the results in May, and they were startling, according to Kaltofen. They showed levels of radium-226 at 76.3 picocuries per gram, and levels of another form of radium common in oilfield waste, radium-228, at 8.66 picocuries per gram. This placed the radioactivity values at roughly 15 times EPA cleanup limits for topsoil at uranium mills and Superfund sites. In other words, according to the lab findings, the sludge accreted to the former Austin Master worker’s boots was so radioactive that the levels would trigger mandatory remediation for topsoil at toxic waste sites. And here it was cloaking their feet. The sludge removed from the boots also showed elevated levels of radioactive lead and thorium.

“This is a lot of radioactivity to bring home,” Kaltofen told Concerned Ohio River Residents on a conference call with the group in late May. “It will be in the floor mats in your vehicle, on your clothes, in your septic system, and therefore in your yard.”

While workers typically left their boots in the company locker room at the end of the workday, Torbett says it was also common for workers to leave for lunch or a work-related errand wearing their sludge-encrusted boots and uniforms. “The same boots I wore on the floor, I’m down at the Sunoco pumping gas in the company truck or running over to the AutoZone to get parts,” says Torbett. He said workers bought their own boots, and only on one occasion during the end of his time at Austin Master was he reprimanded for leaving the facility in work clothes.

“Radium is commonly referred to as a bone seeker,” states a report of the National Research Council Committee on the Biological Effects of Ionizing Radiations. If accidentally inhaled or ingested, the radioactive element tends to accumulate in the bones, where it continues emitting radiation and can lead to cancer.

“Those boots represent a person, and that person represents a workforce,” says Caggiano, the former fire chief. “This tells me that whoever is handling day-to-day hygiene is either incompetent or doesn’t care if that person exists at all and has given their employees slave-like labor status. It further underlines that the state of Ohio’s regulations are just paper tigers and serve no function other than to check a box and to appease an unknowing public.”

He said that as a battalion fire chief entering an environment as contaminated as the Austin Master facility appears to be, he would ensure his firefighters were in full hazmat gear with special non-absorbent hazmat boots and gloves and a breathing apparatus with an air supply tank on their back. And he would only allow the firefighters to be inside for 45 minutes at a time; yet Austin Master’s workers are there eight hours a day, week in and week out, without such protections.

“These results are alarming and it signifies the need for appropriate radiation protection measures in the oil and gas workplace,” adds Bemnet Alemayehu, a Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) staff scientist with a PhD in radiation health physics and co-author of a 2021 report on this issue. DeSmog provided NRDC with Eberline Analytical’s analysis of the worker’s clothing. “Based on the data provided,” says Alemayehu, “it appears the radioactivity levels are high enough to cause” exposure risks to the oil and gas workers.

Torbett says that as far as he recalls, nobody at the Austin Master facility in Martins Ferry wore dosimeters, a device used to measure radioactivity exposure. “The whole time I was there, never once did I see any kind of respirator,” he says, which would provide at least some protection against the inhalation of radioactive particles. According to Torbett, workers like him wore company uniforms that were run through a washing machine at the site that was regularly breaking down, and that after a day’s work, their clothes would be covered in mud and sludge.

“There was sludge everywhere,” he says. “Everywhere.” Torbett, a lifelong Ohio River Valley resident, left work at the facility after just three months, concerned about Austin Master’s operating practices and the manner in which the company treated its workers.

Raising Red Flags

Concerned Ohio River Residents, which received the clothing items from the former worker and sampled the soil on the public road outside the facility, has long been worried about the risks the Austin Master facility posed to workers and the community at large and is in touch with a number of former workers. In mid-August, members of the group toured officials with EPA Region 5 around the area, including a drive-by of the Austin Master facility in Martins Ferry.

Despite the dangers this type of oil and gas waste poses, a 1980 provision enacted by Congress has deemed it non-hazardous and therefore exempt from federal rules that would otherwise apply to hazardous waste. As an EPA spokesperson told DeSmog, “There is no one federal Agency that specifically regulates the radioactivity brought to the surface by oil and gas development.” In a separate exchange, EPA spokesperson Enesta Jones stated: “EPA does not regulate radioactivity in oil and gas production, processing and transport systems.” Jones pointed to state agencies as having the authority to track and regulate oil and gas waste and its radioactivity.

Meanwhile Ohio regulatory agencies appear to be equally hamstrung in their ability to manage or even systematically assess the situation. “The Division does not have the authority to levy fines, none the less, the Division strives to ensure regulated entities are complying with Chief’s Orders, Ohio law and rule,” Stephanie O’Grady, a spokesperson with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, told DeSmog in March. The department did not respond to additional questions regarding sludge samples taken from Austin Master worker clothing.

“The Ohio Department of Health (ODH) has visited the site and taken samples,” and “results are due back soon,” ODH spokesperson Ken Gordon told DeSmog in late July. “ODH also is working with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources on this. ODH will prepare a report, and once that report has been reviewed and approved, we will be better positioned to answer your questions. We expect the report will take at least several weeks to be finalized.” Questions to the agency asking for a more detailed timeline for the report’s release and whether the report will also assess worker clothing contamination have gone unanswered.

Responses from other federal agencies, such as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) have been equally lackluster. OSHA is responsible for regulating radioactivity in the workplace for the oil and gas industry, in standards for “General Industry” that are listed in the federal code under 29 CFR 1910.1096.

“The OSHA Columbus Area Office has conducted two inspections at the facility,” and “the first inspection was opened on July 6, 2015,” says Scott Allen, the Regional Director for Public Affairs and Media Relations with the U.S. Department of Labor, when pressed with a series of questions regarding the high levels of radioactivity in the sludge on the worker’s clothing. “Citations were issued for a fall hazard and for not evaluating the facility for confined spaces,” continued Allen. “The second inspection was opened on May 8, 2017. The complaint items involved exposure to fall hazards, slip and trip hazards, and a leaking roof. Citations were issued for the fall hazards. We did not observe or address any issues regarding the [radioactivity] issues raised [by DeSmog] at the facility during these inspections.”

Industry workers and residents across the Marcellus and Utica shale tell DeSmog it is this general tone of dismissal and inaction from regulators that has them feeling aggravated when it comes to oilfield radioactivity and its harms.

“There have been no data to support the public or workers exceeding” Nuclear Regulatory Commission annual radioactivity limits set for members of the public, David Allard, Pennsylvania’s chief radiation protection officer, stated last year in a Pennsylvania statehouse hearing on oilfield waste. Yet the Nuclear Regulatory Commission has no jurisdiction over oilfield radioactivity and does not test for it.

In an article published online in 2020, the Health Physics Society, an influential organization composed of radioactivity regulators across the nation, stated: “Radiological exposures at the levels experienced in the oil and gas industry are orders of magnitude below where any observable effects will occur and, because of the human body’s natural repair mechanisms, are unlikely to contribute to future cancers.” The article was later taken down without explanation and then revised and reposted, with the passage quoted above altered to read: “Generally speaking, radiological exposures at the levels experienced by most workers in the oil and gas industry are significantly below those where any observable effects are likely to occur, and, because of the human body’s natural repair mechanisms, are unlikely to contribute to future cancers.”

DeSmog presented the Health Physics Society with information and documents concerning the situation at Austin Master, but the group has not replied to questions.

Meanwhile, among certain sectors of the oil and gas industry, concerns over radioactivity exposure are real, and pointed. “Exposure to ionizing radiation, even at low doses, can cause damage to the nuclear (genetic) material in cells that can result in the development of radiation induced cancer many years later (somatic effects), heritable disease in future generations and some developmental effects under certain conditions,” states a 2016 report of the International Association of Oil & Gas Producers on oilfield radioactivity. While radioactivity can damage the skin, breathing or ingesting dust allows the hitchhiker radioactive elements to enter the body and potentially continue their radioactive decay in the lungs or gut, leading to the “irradiation of tissues and organs,” it goes on to note. The report has entire chapters devoted to workplace radioactivity hygiene and procedures, which, according to former workers and the state inspection files, Austin Master does not appear to be closely following in Martins Ferry.

The solutions here do not involve “rocket science,” says Andrew Watterson, an occupational and environmental health researcher at the University of Stirling, in Scotland, who has expertise in oil and gas work. “From the accounts available of working conditions, and the PPE [personal protective equipment] contamination levels provided by the independent analytical lab, it is difficult to establish or conclude that any basic global health and safety management principles have been properly put into practice over time or that effective external oversight of the facility had occurred.”

But fixing this issue in the United States goes beyond just personal protective equipment and straight to lawmakers, says Amy Mall, a senior advocate at NRDC. “We need Congress to act to end the dangerous oil and gas loopholes in our federal laws, including the gap for naturally occurring radioactive materials,” says Mall. “In addition, we urge the EPA to investigate this situation and other oil and gas waste sites around the country, and to revise its rules to reflect current knowledge about the risks to human health and the environment.”

The biggest critic, however, might be a former worker. When asked about the EPA regulations, and informed about the exemption on oilfield waste, Bill Torbett commented: “I do feel that whatever government agencies are involved, they are kind of to blame. I really feel like it should be figured hazardous until somebody can verify it is not, not the other way around like it is now. I mean, let’s treat this gun as if it is loaded.”

While Waiting for Governments to Act, Citizens Are Stepping in

In July, Concerned Ohio River Residents and other Ohio advocacy groups sent a letter about Austin Master to EPA Administrator Michael Regan.

“We have identified environmental justice and human rights abuse under President Biden’s Executive Order 13985,” the letter stated. “Understanding your values and heavy emphasis on pushing for environmental justice, we call upon the United States Environmental Protection Agency to address disproportionately high and adverse health and environmental impacts on low-income populations here in Appalachia…We call upon your Office to investigate these issues because no other governmental or regulatory agency is stepping up.”

EPA Administrator Regan’s office has not replied to questions on the matter. Meanwhile, as additional facilities threaten to set up shop in the region, Ohio residents are moving forward on their own to hold accountable the industry and the government agencies tasked with regulating it.

Teresa Mills, director of Buckeye Environmental Network and a longtime advocate for environmental justice in Ohio communities, says she is happy that top EPA officials are now listening to Ohio groups concerned about radioactive oilfield waste and its inappropriate handling and treatment. However, she laments that the agency has still done nothing on the ground in terms of analysis, formal investigation, or testing. “I told EPA, ‘citizens are now forced to do your jobs,’” says Mills.

In early July, Mills helped organize an informational session at a hotel in eastern Ohio intended to train everyday Ohio residents in how to sample their roadways, parks, and backyards for oilfield radioactivity contamination. The session was led by the former Ohio battalion fire chief, Silverio Caggiano.

The reason for the training, explained Mills, is because the oil and gas industry has threatened their communities and workers with radioactivity contamination, and if the state and federal regulatory agencies are not going to stand up to protect them, then Ohio citizens will do it themselves. “Nobody is regulating oil and gas waste,” says Mills. “No one is touching it, this is insane.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts