In the aftermath of last month’s toxic train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, questions and concerns about the adequacy of rail safety regulations have resurfaced. The train, owned by Norfolk Southern, was transporting chemicals and other hazardous materials when an overheated wheel bearing led to a catastrophic derailment on February 3. The subsequent disaster response included a localized evacuation and a controlled burn of hazardous substances contained in the derailed tankers, including the carcinogenic chemical vinyl chloride, fouling the air and leaving residents worried about their health and safety upon return.

Nearly three years ago to the day, another disaster involving leakage of a hazardous material similarly sickened residents and forced the evacuation of a small town, this time in Mississippi. On February 22, 2020, a 24-inch pipeline transporting highly pressurized carbon dioxide (CO2) contaminated with a small amount of hydrogen sulfide ruptured in the town of Satartia, sending a large toxic plume into the surrounding area. Around 300 people were evacuated and nearly 50 hospitalized. More than 100 people were sickened, many of whom have had lingering symptoms like cognitive impairment, reduced lung capacity, PTSD, and chronic fatigue.

While these two disasters involved different hazardous substances and modes of transport, they have one thing in common: both were under the purview of the same federal agency, the Pipeline and Hazardous Material Safety Administration (PHMSA). Experts are now saying that these accidents demonstrate the consequences of inadequate oversight and insufficient safety regulations governing hazardous material transportation.

“I think there’s no question that the safety regulations were not sufficient,” Ted Schettler, a physician and environmental health expert and the science director of the Science and Environmental Health Network (SEHN), said in reference to the train derailment. He explained that the Satartia and East Palestine incidents were similar because they both involved exposure to hazardous liquids.

“It reminds us that whether we’re sending hazardous liquids through pipes or by trains, they are hazardous liquids and they represent a real threat when people get exposed to them. It should make us think long and hard whether our safety regulations are sufficient,” he said.

PHMSA, which is part of the U.S. Department of Transportation, is in charge of regulating the transport of hazardous materials, whether by rail or pipeline. The agency has faced criticism over its “insufficient oversight” and propensity — especially under the Trump administration — to prioritize industry profits over public safety. In May 2020, the agency struck down an attempt by Washington state to impose a safety rule on trains carrying volatile oil, arguing that states “cannot use safety as a pretext for inhibiting market growth.” Critiques of and concerns about PHMSA have abounded for years; as DeSmog reported in 2015, Rep. Jackie Speier (D-CA) testified at a hearing on oil-by-rail and pipeline safety that the regulatory system is “fundamentally broken,” calling PHMSA a “toothless tiger.”

Carbon Dioxide Pipelines are ‘Dangerous and Under-Regulated’

PHMSA’s record of questionable hazmat oversight raises alarm for some environmental advocates who are fighting several proposed CO2 pipelines in the upper Midwest. Three pipelines are currently planned to transport captured CO2, mostly from ethanol production, to underground injection wells in North Dakota and Illinois. Summit Carbon Solutions wants to build a 2,000-mile pipeline to transport CO2 from over 30 ethanol plants in five states. Another company called Navigator CO2 Ventures has proposed a similar 1,300-mile CO2 pipeline running through five states. A third project from a firm called Wolf Carbon Solutions involves a 350-mile CO2 pipeline in Iowa, the state that is at the epicenter of all three pipelines.

Carolyn Raffensperger — an environmental lawyer, advocate, executive director of SEHN, and Iowa resident — sees the train derailment in East Palestine as a stark example of what can happen in the absence of adequate safety regulations, which she said applies to pipelines just as much as it does to trains.

“When we look at the accident that happened in East Palestine, there were regulations that were possible that were not put in place. Now we have a place that will be contaminated indefinitely,” she said. “What will we be doing with these [CO2] pipelines that we don’t have much experience with?”

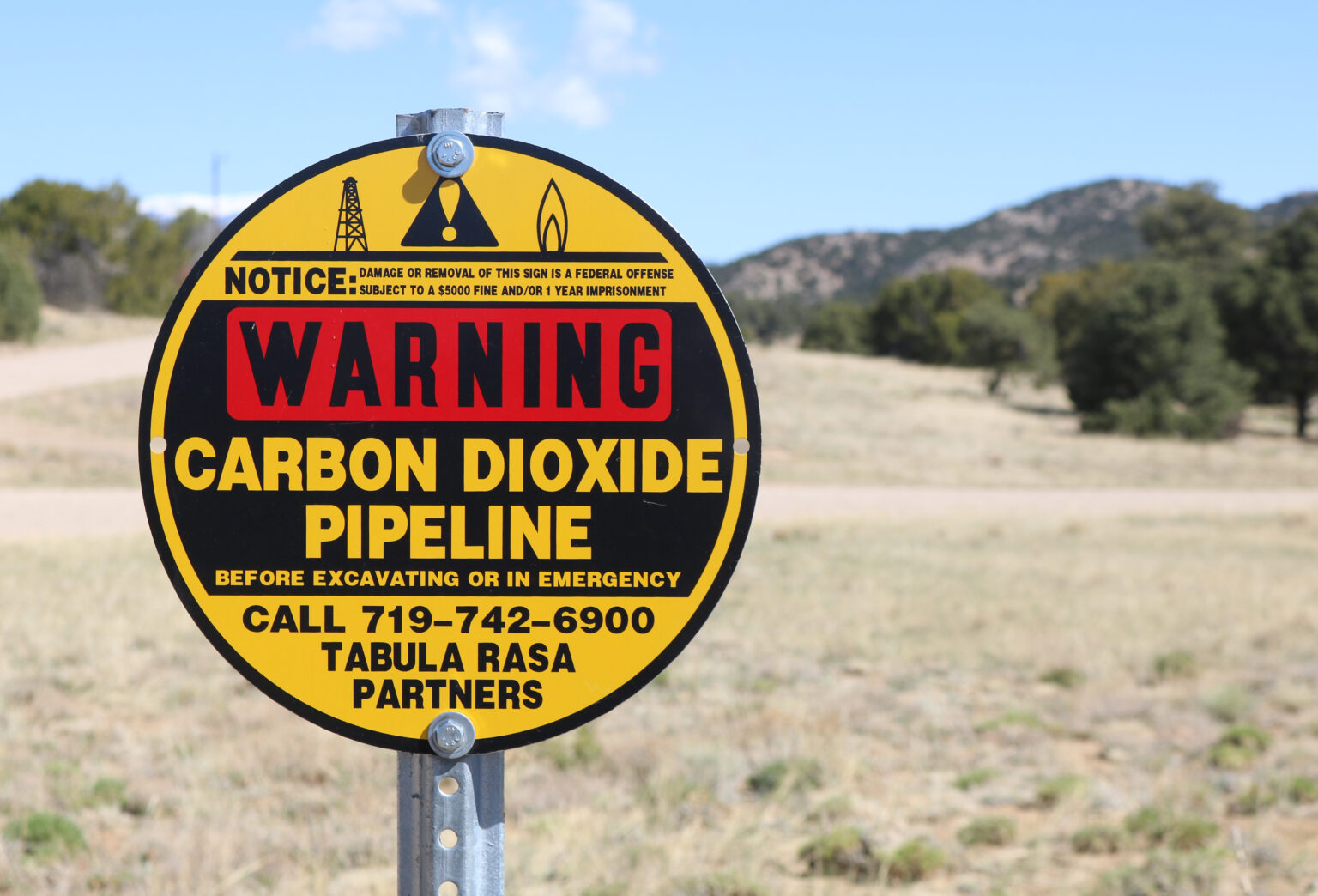

There are roughly 5,000 miles of existing CO2 pipelines in the United States and they are mainly sited in remote areas transporting CO2 to oil fields for drillers to use to extract more petroleum in a process called enhanced oil recovery. But the federal government’s significant funding boost for carbon capture and storage (CCS) is propelling a surge of project proposals to capture and transport CO2, despite the relatively limited experience with effectively and safely operating the technology and infrastructure.

The vast majority of CCS projects attempted in the United States have underperformed or failed, and the primary method of transporting carbon dioxide — in a highly pressurized and compressed state through pipelines — is exceptionally dangerous and under-regulated. As a June 2022 Congressional Research Service brief states, “CO2 pipelines pose a public safety risk, as demonstrated by a 2020 CO2 pipeline rupture in Satartia, [Mississippi].” And current safety regulations for these pipelines contain glaring gaps and deficiencies, according to a report published in March 2022 by Pipeline Safety Trust, a watchdog group advocating for improved pipeline safety.

“There are little to no regulations around appropriate siting, limiting dangerous and corrosive impurities, or building the pipelines to withstand the unique properties of transporting high pressure CO2,” Pipeline Safety Trust executive director Bill Caram said in a press release accompanying the report. Furthermore, existing PHMSA regulations only apply to CO2 of more than 90 percent purity and transported in a supercritical state, meaning it has some properties of a gas and some of a liquid. Pipelines carrying CO2 in a gaseous or liquid state with less than 90 percent purity are completely unregulated, Pipeline Safety Trust says.

Among the most concerning regulatory gaps for CO2 pipelines are the lack of standards regarding impurities or contaminants within CO2 streams, and inappropriate regulations to determine a potential impact area in the case of a failure, Caram told DeSmog. Impurities, including water, can corrode standard steel pipes; if the contaminants are chemicals like hydrogen sulfide, sulfur dioxide, or nitrogen oxides, they can pose a public health hazard in the event of a failure. And should there be a pipeline failure, determining the potential impact area involves complex modeling of the behavior or dispersion of the CO2 plume. Neither accurate technology to do this modeling nor regulations requiring it exist yet, Caram explained.

“We believe that CO2 pipelines are inherently dangerous. By closing the glaring safety gaps with some common-sense regulations, PHMSA can help ensure that CO2 pipelines will meet some basic safety standards they currently lack, but we will continue to advocate for more safety standards once the recommendations from our report are implemented,” Caram told DeSmog via email.

During a webinar hosted by Climate Investigations Center in October on the topic of CO2 pipeline safety and the Satartia disaster, Caram issued a blunt warning: “It is clear to me we are not ready to safely build these pipelines, and if we do, people could die.”

The Health Hazards of CO2

Caram’s warning is not an exaggeration. Exposure to CO2 from a ruptured pipeline is potentially lethal. That is because the gas is both a toxicant and an asphyxiant, meaning it is hazardous to human health and deprives the body of oxygen. And since it is colorless and odorless, exposure can be difficult to detect. “People who are exposed to carbon dioxide often don’t know it because you can’t smell it, can’t taste it, you can’t see it. In occupational settings for example when people are exposed to CO2 they just suddenly die without being aware that they’re in trouble,” Schettler of SEHN said.

Exposure to CO2 even at relatively low levels can trigger breathing problems, the onset of confusion, and unconsciousness. “At just 4 percent [exposure level] it’s immediately dangerous to life and health. At 10 percent it can cause death within minutes,” Schettler explained.

The Satartia disaster was the first known incident of mass exposure to pipeline CO2 anywhere in the world. But as pipeline developers backed by government incentives rush to build out a massive CO2 pipeline network, it’s unlikely to be the last. Investigative journalist Dan Zegart of Climate Investigations Center, who reported extensively on the CO2 pipeline rupture in Satartia, said there is “absolutely” a real risk that we’ll see another CO2 pipeline disaster.

That raises real questions about the potential public safety impacts of proposed CO2 pipelines, especially given the current lack of adequate safety regulations. “The regulators are still trying to figure this out,” Schettler said.

‘Operators are Responsible’ for Pipeline Safety

Following a formal investigation into the CO2 pipeline failure in Satartia, in May 2022 PHMSA announced some measures to improve CO2 pipeline safety, including initiating a new rulemaking to update pipeline safety standards. The new proposed regulations are not expected to be released until October 2024, and then there will be a public comment process before any final rule is issued. Pipeline opponents are calling for authorities to order a moratorium or pause on any CO2 pipeline permitting until federal safety rules are complete. California has already placed a moratorium on certain CO2 pipelines pending the finalization of federal safety regulations.

In late November, 30 organizations wrote to PHMSA requesting that the agency issue an advisory that states hold off on approving CO2 pipelines until its rulemaking is complete. They also requested that PHMSA hold a public meeting on CO2 pipeline safety to gather input from stakeholders and experts in areas such as public health and environmental justice. Pipeline Safety Trust wrote to PHMSA on February 17 echoing the call to convene a public meeting.

“We asked [PHMSA] to hold the meeting where folks are facing the unknown risks of these pipelines coming to their communities, listen to their concerns, and inform them of the steps PHMSA is taking to ensure their safety,” Caram told DeSmog. He said the intent is to ensure the meeting is genuinely for the public, adding, “I think PHMSA is used to doing these meetings mostly for the industry because they have been the most engaged stakeholder for a long time.”

PHMSA declined to comment specifically on the requests, but an agency spokesperson told DeSmog that PHMSA does not have authority to implement a moratorium preventing all pipeline construction.

“While PHMSA establishes minimum safety requirements, operators are responsible for operating pipelines safely, which may necessitate taking mitigative measures beyond what is required explicitly by regulation,” a PHMSA spokesperson said in an emailed statement.

However, companies seeking to build CO2 pipelines in the Midwest, such as Summit Carbon Solutions, are currently clamoring to get their projects permitted despite the lack of updated federal safety rules. This has community members like Raffensperger concerned that the companies are not taking their pipeline safety responsibility seriously.

“Pipeline companies can’t have it both ways. Either they need to wait until PHMSA both acquires the science needed to draft regulations and then finalizes the regulations or the companies have to own up to the fact that they are flying blind by building these CO2 pipelines in the absence of meaningful rules,” she said. “They can’t say with a straight face that PHMSA regulations guarantee safety when they are trying to get pipeline permits before PHMSA finishes the rule-making process.”

The companies are also pushing to withhold certain safety data from state regulators. They argued that they shouldn’t have to submit key safety information in their applications since the federal government has sole jurisdiction over safety — and the Iowa Utilities Board recently agreed to reverse its earlier decision requiring submission of safety data.

The federal government is leaving our communities out to dry. Federal safety regulations fall short, but states are preempted from considering safety. https://t.co/W4qIWGnild via @EENewsUpdates

— Pipeline Safety Trust (@pstrust) February 15, 2023

The IUB decision allowing Summit Carbon Solutions to withhold safety data specifically pertains to an emergency response plan and to plume modeling and risk assessment. On its website the Iowa Utilities Board states that it “does not have safety jurisdiction over hazardous liquids pipelines. The U.S. Department of Transportation Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) has that authority.”

“The best states could do is wait for PHMSA to issue the regulations and they’re not even doing that,” Raffensperger said. The IUB is proceeding with public hearings on Summit’s permit application starting this fall. Summit announced it applied for its permit in Iowa on February 1, 2022. Navigator submitted its application in Iowa last October, and Wolf just filed for an application in February; public hearings have not yet been scheduled for these pipeline proposals.

Until PHMSA completes its rulemaking on CO2 pipeline safety, pipeline companies like Summit “are going to be deciding on their own what safety regulations they’re going to develop and utilize,” Schettler said.

“If they do proceed before PHMSA figures out their final regulations, we’ll just have to see whether they’re sufficient or not,” he added.

Raffensperger is convinced that even updated safety regulations from PHSMA will not be enough to ensure public safety, let alone leaving safety decisions up to the pipeline companies.

“These [CO2 pipelines] cannot be built in a way that will guarantee safety,” she said.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts