Oregon state environmental regulators are deciding whether to issue an air permit for a contested oil-by-rail operation in Portland, a site that received local approval after a deal worked out in private between the company and city officials.

Now, new documents show that the state agency also met privately with the company before the application was submitted.

The agency said the meeting was informational and involved no commitments. But for groups that oppose oil-by-rail in Portland, the documents add to the sense that multiple layers of government are favoring the company’s interests over public health and safety.

Zenith Energy is a Houston-based oil company that operates the Portland terminal. Crude oil is shipped there by rail, transferred to vessels on the Willamette River, and shipped out through the Columbia River to ports along the West Coast.

For years, a coalition of environmental groups, neighborhood associations, and other community organizations have opposed Zenith because oil train derailments pose significant environmental and safety risks — trains carrying oil or refined products can explode. Portland received a reminder of rail dangers when a freight train unconnected with the site derailed in late April.

Last year, a DeSmog investigation revealed that Portland’s city government — two elected city commissioners and their staff in particular — met privately with Zenith in July and August 2022 to discuss how the company would transition from handling crude oil to renewable fuels at its rail site. Because the city had rejected a previous land use permit and state courts refused to overturn the decision, Zenith’s operations were in legal peril. But the city worked behind closed doors with Zenith to coordinate a new permit, approved in October 2022.

That “backroom deal,” as critics called it, allowed Zenith to continue its oil shipments for five more years, with the promise to switch to renewable fuels thereafter.

It also gave Zenith a formal blessing by the City of Portland, an about-face by a municipal government that spent several years publicly opposing oil train operations. The city recast Zenith as a partner, rather than a villain, in the fight against climate change because of the professed commitment to gradually transition to renewable fuels.

None of those private communications, including at least two in-person meetings at Zenith’s oil terminal in the summer of 2022, had been disclosed to the public. The DeSmog investigation showed that elected city officials and their staff were heavily involved in a deal that prolongs oil-by-rail operations.

The new documents reveal that the city was not the only governmental entity meeting with Zenith behind closed doors.

Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) had at least two discussions about the Zenith matter, first with Portland officials and then with the company, during the period that the city was working to forge a new relationship with the oil company.

On July 12, 2022, DEQ held a meeting with a group of Portland officials from multiple bureaus, as well as the staff of city commissioners, where they discussed a possible new land use permit — called a land use compatibility statement (LUCS) — for Zenith.

“Settlement talks? Zenith discussion – LUCS denial or agree to conditions,” Portland Supervising Planner Tom Armstrong wrote in notes from the meeting, a reference to ongoing litigation against Zenith. The notes were obtained through a records request by a climate nonprofit called Breach Collective and shared with DeSmog. The document appears to suggest Portland and DEQ were discussing or brainstorming possible paths forward regarding Zenith and what that would entail.

“Can City issue LUCS with conditions? Withdraw permit, resubmit with conditions/limits incorporated into application,” the notes read.

A month and a half later, several officials from DEQ held a Microsoft Teams meeting with Zenith’s Grady Reamer and the company’s law firm, Stoel Rives.

Handwritten notes from a DEQ staffer who attended the meeting, also obtained by Breach Collective, shed some light on what was discussed.

Reamer, a vice president for Zenith’s U.S. operations, and his attorney took turns presenting the company’s vision to DEQ. That included the pivot from crude oil to renewable fuels at its Portland rail terminal. Crucially, the transition would allow the city to greenlight a new land use permit, rescuing Zenith from a potential shutdown threat.

Zenith needed the LUCS from Portland to apply to DEQ for a state air permit. The handwritten notes detailed what DEQ would do to help Zenith realize this vision.

“DEQ would: withdraw denial of [air permit] → once LUCS received,” the notes said. Another bullet point said the agency would “work together to process expeditiously,” potentially referring to the air permit Zenith needed. When asked about this entry, a spokesperson for DEQ told DeSmog that the DEQ staffer was simply recording Zenith’s statements at that meeting, and DEQ did not commit to anything.

This discussion occurred prior to Zenith submitting an application to either the city or the state — its land use application was not filed with Portland until early September.

“In the context of everything that is going on, this is really interesting because on August 24th, no one except the city, Zenith, and now DEQ know that these conversations are taking place,” Nick Caleb, an attorney at Breach Collective, told DeSmog. “There’s an active lawsuit at the same time. DEQ is basically in negotiations with a party to that litigation over how to protect its interests. That’s how this reads to me.”

Lauren Wirtis, communications manager for DEQ, said the agency was only there to listen.

“This Aug. 24, 2022 meeting happened because Zenith wanted to share an update with DEQ,” Wirtis said in a written statement. “The notes capture what Zenith conveyed to DEQ about changes they intended to make at their facility, the status of their LUCS with the city and what they expected were their next steps in DEQ’s air quality permitting process. This meeting was a one-way sharing of information.”

DeSmog asked if there was a precedent for DEQ having discussions with a company in advance of an application when the company was in litigation over the matter. Wirtis did not specifically address that question, but she said, “DEQ will meet with anyone to discuss a permitting process. Many entities have questions about how permitting works before they apply for permits. We also talk with environmental advocacy groups and communities.”

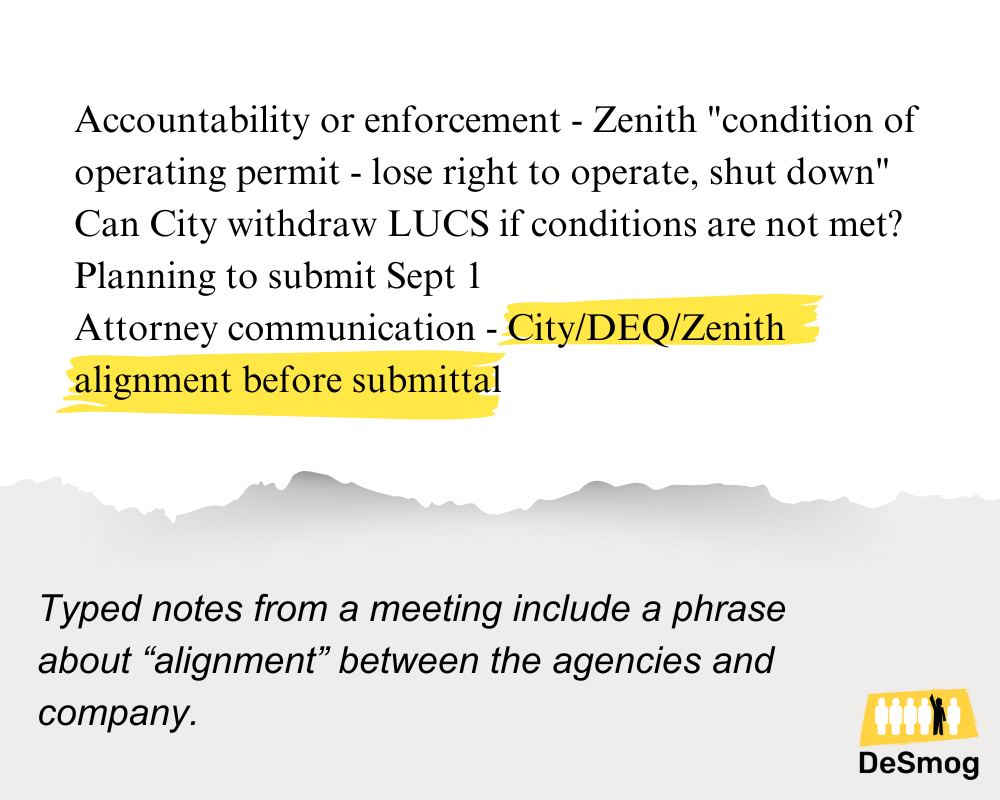

Another internal document from a Portland official discussing Zenith suggests some degree of understanding between all three entities. “Attorney communication – City/DEQ/Zenith alignment before submittal,” the notes of an August 30 meeting state.

The idea of “alignment” on the application before it was made public adds to opponents’ belief that the city process was a foregone conclusion.

“The city basically already decided to move forward with approving this new land use compatibility statement. They’re basically coordinating to pre-approve a decision,” Caleb said. “So, that just shows that the formal review is a sham review.”

Magan Reed, a spokesperson for Portland’s Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, said it was a different sort of alignment under discussion.

“The City met with DEQ and Zenith to ensure our collective understandings of scope of authority, roles and responsibilities were in alignment,” Reed said in a statement. “We had been working with the applicant to add requirements to the City’s Land Use Compatibility Statement and we needed to better understand how those additional requirements would interact, or if they could at all, with any future DEQ application process.”

Reed added that meeting with applicants is typical. What was unique about this situation was the proposed conditions of the land use permit, to which both Portland and Zenith agreed.

“What went beyond the standard process in this situation was our request, and the applicant’s agreement, to put additional conditions concerning the phase out of crude-oil transports within five years and several compliance measures for enforcement, amongst other requirements,” Reed said.

DEQ, for its part, said it did not advise Zenith or the city on land use matters.

”DEQ never makes commitments about permitting because that would be premature,” Wirtis said. “In this meeting, DEQ did not confirm any next steps or commit to the issuance or timing of any environmental permits.”

Environmental groups said it raises red flags that DEQ met with Zenith at a time when the company was in litigation over its future use of that site. The meetings give the appearance that the state environmental regulator is helping an oil company resolve its legal woes, they said.

“It’s highly concerning that the city and DEQ are making this level of effort to assist Zenith in getting this, particularly given the massive public opposition and the fact that they’re doing this behind closed doors without any public input,” Kate Murphy, a senior community organizer at Columbia Riverkeeper, told DeSmog.

Columbia Riverkeeper played a formal role in helping Portland defend its rejection of Zenith’s prior land use permit. The city did not inform the group that it was changing course and partnering with Zenith on a new strategy, Columbia Riverkeeper said.

“DEQ’s job is to protect the environment, not to help industry find ways to negotiate loopholes to get their permits in place and keep them operating,” she said.

Zenith did not respond to questions from DeSmog. But in public statements, the company highlights its partnership with the Portland city government.

“Renewable fuels are a critical part of the City of Portland’s and the State of Oregon’s efforts to address climate change,” Zenith’s Grady Reamer said in August 2023, noting progress on its transition to renewable fuels. “We share the goal of expanding the availability of low-carbon, renewable fuels, and we’re proud to join the City’s efforts by utilizing our existing energy infrastructure to make this a reality.”

The Public Has ‘No Real Way to Meaningfully Engage’

The documents are particularly relevant because DEQ is now in the process of reviewing Zenith’s air permit request. A public comment period is expected to open this spring.

Following DeSmog’s August 2023 investigation, a coalition of environmental groups and local neighborhood associations sent a letter to DEQ, asking the agency to review the manner in which Portland approved its land use permit. The groups hoped that the state regulator would essentially toss out the approval.

Last fall, DEQ said it did not have the authority to do so.

“We were a bit confused as to why they were interpreting their powers so narrowly,” said Caleb, the Breach Collective attorney. The new documents “clarify things for me,” he said.

“They were in conversation with the city and Zenith during this period of backdoor communications,” he said. “It makes a lot more sense to me why they would interpret their rules narrowly to avoid looking into their own role in this.”

When asked about the documents, Mary Stites, an attorney with Northwest Environmental Defense Center, another opponent of Zenith, said she was “disappointed but not surprised.”

“I think it raises a lot of questions about how our state agency coordination program is supposed to work,” she told DeSmog.

By the time a proposal reaches the public comment period, when residents ostensibly have a chance to influence the outcome, it too often seems like a fait accompli, she said.

“Advocates like us and the public have no real way to meaningfully engage in a timely manner,” Stites said. “And so that’s really, really troubling.”

An environmental coalition, including Breach Collective and Northwest Environmental Defense Center, decided to take the matter one step further, petitioning the Oregon Environmental Quality Commission, a state body with partial oversight over DEQ. The environmental groups are asking the commission to declare that Portland’s approval of the land use permit was not legally sufficient, and to either toss it out or remand it back for a do-over. The Environmental Quality Commission will decide at a May 23 public meeting.

“DEQ’s job is to wait until it gets documents from the city in the form of a land use compatibility statement and then evaluate the legal sufficiency of that document,” Caleb said. “And it’s hard to understand how DEQ could do that with any kind of objectivity when they’re deeply involved in the process of, apparently, Zenith getting their LUCS in the first place.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts